EVs: the biggest lever in driving the energy transition

Transport is a massive emitter — electric vehicles offer a road to redemption for the sector

1 minute read

Along with hydrogen and solar, electric vehicles are one of the key technologies which will fuel the energy transition. Fortunately, after something of a slow start, global electric vehicle (EV) sales are accelerating. Many governments are aiming to drive uptake with legislation, however, it remains to be seen if ambitious targets for EV sales can be met.

Why we need to embrace EVs

Transport is a massive contributor to global warming, accounting for around 16% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2019. In fact, in the world’s three largest car markets the problem is far worse: in China transport generates 25% of emissions, in Europe 27% and in the US a whopping 29%. While travel restrictions during the Covid-19 crisis saw these numbers drop, they are rapidly closing back in on pre-pandemic levels.

Transport’s high share of greenhouse gas emissions make it an exceptionally important segment to decarbonise. With that in mind, a key element of the energy transition will be to coax consumers away from internal combustion engined (ICE) vehicles and into EVs. Up to three-to-four times more energy efficient than ICE vehicles, EVs are the best way of shifting emissions away from exhaust pipe. What’s more, unlike other technologies such as hydrogen, EVs have already been proven in the field at scale.

What’s been stopping us?

Until recently EVs were proving something of a hard sell. Given our longstanding love affair with petrol-powered vehicles, that’s perhaps unsurprising. The human race has spent well over a century adapting to the peculiarities of the internal combustion engine; that makes the idea of a car which (apart from being better for the environment) is almost silent and largely odourless less appealing than it should be. The problem is that, unlike, say, a Nokia-style mobile compared to a smartphone, EVs offer nothing extra for the end user. Concerns around range anxiety, access to charging and upfront affordability were also significant barriers to uptake.

Global EV sales have turned a corner

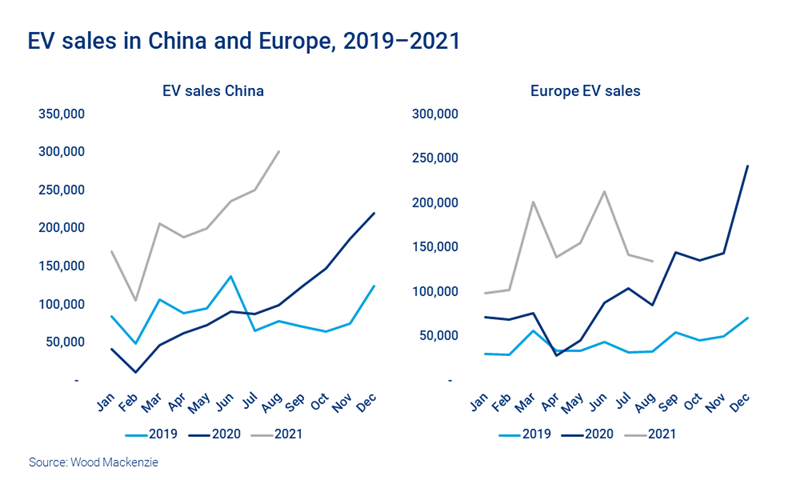

Fortunately, global EV sales are on the rise. In fact, they’ve skyrocketed in 2021: sales in the first eight months of the year have been two and a half times higher than in the same period last year. That means 20% more EVs were sold in those eight months than in the whole of 2020, which was itself a record year despite the pandemic.

Despite supply chain issues, especially with batteries, in China and Western Europe one of every five new cars currently being sold is an EV. In China, manufacturers have found their way around shortages by leaning heavily on small, short-range battery electric vehicles (BEVs) such as the Wuling Mini microcar. Meanwhile, European carmakers have focused on plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) — cars with both a petrol engine and an electric motor which are often based on existing ICE models — such as the Mitsubishi Outlander and Ford Kuga. Both types of vehicles employ a 10-12 kWh battery pack, compared to battery packs of around 65 kWh in a typical mid-size BEV.

Global adoption targets vary

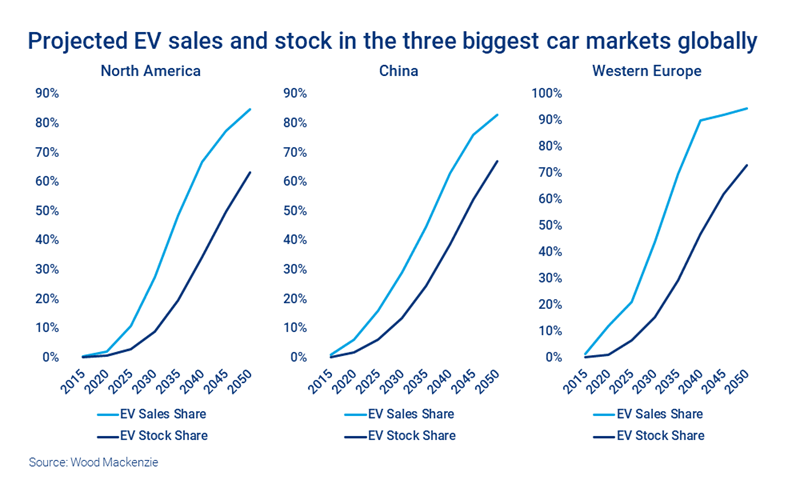

Automakers representing 80% of total global car sales have pledged to become carbon neutral; as already mentioned, EVs offer the most viable and effective path towards that goal. However, while countries representing over 50% of all car sales have made similar net-zero pledges, the details of adoption targets vary.

Emissions regulations in Europe are very aggressive. With sales of new ICE vehicles due to be phased out in European Union countries by 2035, EVs will become the default choice. We think the EU’s goal may be ambitious, but it should come close to achieving it.

China’s targets are more pragmatic, targeting a 50-50 split of sales between EVs and hybrids by 2035. This seems eminently achievable, in fact, in recent months China has actually been ahead of its current target for EV sales.

In the US, President Biden signed an executive order in August 2021 targeting 50% EV sales by 2030. However, emissions regulations have so far only been set up to 2026 and are rather lukewarm, so they do little to support this target. What’s more, an update to the EV incentive program is stuck in political gridlock with the huge infrastructure bill currently before Congress. Unless the situation changes significantly, we expect the US to be at less than 30% EV share by 2030, and slightly below 50% by 2035.

Overall, the accelerating uptake of EVs is encouraging, while targets and legislation are going in the right direction. However, issues including a massive increase in demand for battery raw materials will need to be addressed on the road to a truly low-carbon economy.

Read more of our COP26 content.