Deepwater investment bounces back

How to enrich the opportunity set in greenfield oil projects

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Can emissions taxes decarbonise the LNG industry?

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

-

The Edge

Can carbon offsets deliver for oil and gas companies?

-

Featured

Wood Mackenzie 2023 Research Excellence Awards

-

The Edge

Nuclear’s massive net zero growth opportunity

-

The Edge

Hydrogen: how carbon intensity rules can muddy the waters

Momentum is building. Overall upstream investment is set to rise for the third year in a row following the 2016 low, albeit at a modest, single-digit rate. And it’s not just the US L48. The conventional sector is generating its own flow of major new projects coming forward for FID. The wheels are turning again.

The nadir for investment was 2015 when projects sanctioned brought forth a measly US$60 billion of spend. Ian Thom, Director, Upstream, identifies 115 major capital projects over 50 mmboe that have been approved for development since then, with combined spend of almost US$500 billion. This year’s batch of FIDs may fall short of last year’s, which involved US$190 billion of committed spend – but not by much. Importantly, the mix is changing.

The industry was, unsurprisingly, risk-averse in the early years of the downturn. Capital earmarked for new projects avoided the complex. Instead, the focus was on low cost and speed to revenue. That didn’t exclude projects with big reserves and long life. Such projects in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Canada, UAE and Israel accounted for around 41 billion boe, or 57%, of the reserves sanctioned since 2015.

Deepwater FIDs ticked along, with the focus on simplicity, throughout this period. Most were tie-backs to existing infrastructure. Zohr and Mad Dog were rare examples of bigger developments, but the majority of the other larger, more complex projects were economically challenged. Now things are starting to pick up. This year is shaping up to be the best since 2013, with project sanctions potentially hitting US$80 billion in total capex, up from just US$20 billion last year.

How deepwater projects have bounced into economic relevance is a story worth telling

Pre-FID project breakevens were US$79/boe (NPV15) in 2014. Our latest dataset clocks in at US$50/boe, a fall of 37%. The main levers have been cost-cutting, portfolio high-grading and design optimisation. Average capex/boe has fallen by 60% to under US$8/boe. Overcapacity in the service sector has helped, including driving down drilling costs.

As important is the change in philosophy. Angus Rodger, Director, Upstream, says the industry recognised that delays in project execution seriously eroded value. Operators have focused on bringing fields onstream quicker via simpler development concepts and standardisation, and by breaking more complex projects into successive phases. The average time from FID to first production is now less than three years.

Gas projects are prominent among deepwater FIDs in the coming years. A major new phase of LNG investment is underway, with US$200 billion of projects likely to be sanctioned between 2018 and 2021. Among these is a clutch of deepwater projects, including BP’s Tortue (Senegal, FID in December 2018) and the first of the two giant Mozambique projects, Anadarko’s Area 1 (sanctioned this week). ExxonMobil’s Rovuma is due to follow suit in H2 2019.

Deepwater oil projects are also moving toward sanction. Chief among them are the giant projects in Brazil, notably Petrobras’ expansion phases of the Mero, Roncador, Marlim, Sepia and Buzios fields. In Guyana, Phases 3 to 6 of ExxonMobil’s Liza complex are moving through the pipeline.

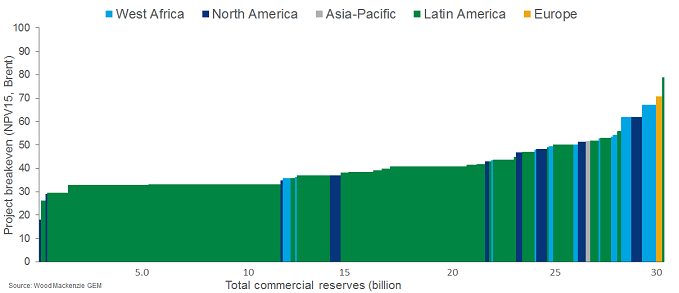

These are world-class projects, with breakevens to match the best US tight oil plays. Even so, pre-FID deepwater oil projects will make up only a modest proportion of future oil supply – around 3 million b/d, just one-fifth of the new supply we expect will be brought onstream from pre-sanction projects next decade. There are plenty of deepwater oil discoveries around the world. Outside Latin America, too few are competitive.

There’s still work to be done to get deepwater costs down, though there are limits to what the industry can achieve on its own. Risks to cost inflation include drilling costs. We have argued that deepwater rig day rates could rise substantially in the next few years.

Governments need to recognise the role they can play to enrich the opportunity set. Oil and gas companies are in thrall to capital discipline and, for the foreseeable future, will continue to be highly selective in what and where they invest. It’s a competitive world. Countries that don’t get the balance right between prospectivity and fiscal take will risk watching the dollars flow elsewhere.