Five constraints on US tight oil production

Can the sector return to a growth path?

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Can emissions taxes decarbonise the LNG industry?

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

-

The Edge

Can carbon offsets deliver for oil and gas companies?

-

Featured

Wood Mackenzie 2023 Research Excellence Awards

-

The Edge

Nuclear’s massive net zero growth opportunity

-

The Edge

Hydrogen: how carbon intensity rules can muddy the waters

The 2020 collapse in oil price hasn’t just killed tight oil’s growth, it smashed volumes down in the space of just a few months. After near-relentless growth since the price-driven low of 2016, total US Lower 48 oil production had climbed to a monthly peak of 10.3 million b/d by March 2020. Output today is just over 9 million b/d, and that includes virtually all the wells shut-in during the spring downturn which are now back in production.

The big question is whether tight oil will ever return to a growth path. Much depends on price – more on that later. Linda Htein, Head of US L48 Analysis, has identified five other factors that suggest tight oil growth will never be as rampant in future; and any new peak in tight oil production will be lower than prior forecasts.

Operators today are under extreme duress from banks and shareholders simply to generate free cash flow.

First, we’re in a new age of austerity. Operators today are under extreme duress from banks and shareholders simply to generate free cash flow. Some are even framing a new business model that limits reinvestment to 65% to 80% of operating cash flow compared with as much as 120% in the recent past. Any surplus cash will be used to pay down debt or returned to shareholders.

Second, there’s zero appetite for risk. Drilling inventories have been reduced to the core; secondary benches and exploration won’t feature in spending plans.

Third, there’s little likelihood of the kind of quantum leap in efficiency and cost reductions we saw last time around – not with the oil field services sector on its knees.

Fourth, there’s heightened policy risk with the presidential election next month. Before this year’s price crash, the sector flourished as the Trump administration systematically reversed rules on the broader energy market imposed during previous administrations.

A win for Joe Biden could mean stricter limits for gas flaring and leakage on federal land. It could also mean no new federal land being opened up for drilling, although that is expected to have very little impact on total production. Infrastructure projects will likely be susceptible to delays, take longer to execute and cost more. In any case, ESG pressures are growing and may prove to be far more consequential for tight oil’s future.

Fifth, the sector consolidation that’s been sparked by the downturn will lead to less investment, not more. The industry needs fewer players. Combinations like ConocoPhillips/Concho Resources and Pioneer Resources/Parsley – the third- and fourth-biggest tight oil deals so far this downturn – will reduce costs, improve efficiency and boost resilience.

But refocusing on the core of a combined drilling inventory will mean fewer new wells and further reductions in capital budgets for 2021. Higher cash flow for each barrel produced perhaps – full circle back to Linda’s first point – but less cumulative tight oil production.

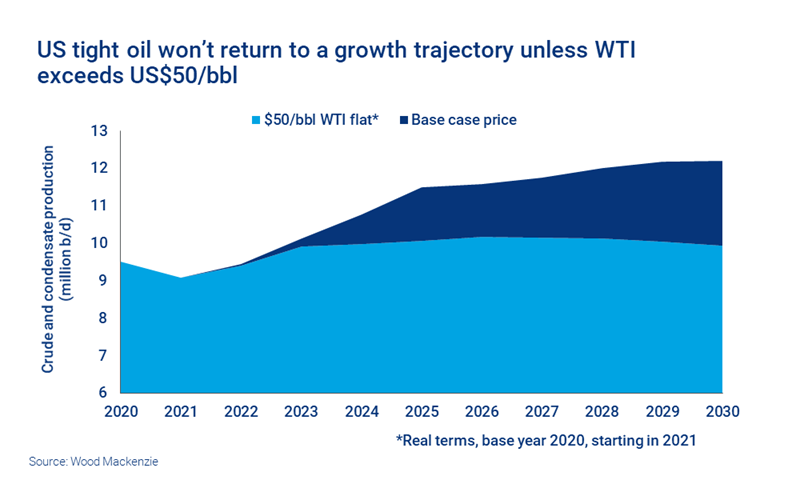

Despite these impediments, we expect US tight oil production to start growing again as oil prices recover, though little or no growth will come through before 2022. We forecast US L48 oil volumes climbing to 11.7 million b/d in 2027. That growth is based on WTI averaging in a range of US$50 to US$60 per barrel for 2021, which depends on a sustained recovery in global oil demand. The new tight oil peak is 0.8 million lower than we forecast a year ago and comes two years later.

On a flat US$50/bbl WTI price, the near 3 million b/d growth from today’s level to 11.7 million b/d just won’t happen. Ann-Louise Hittle, Head of Macro Oils analysis, reckons at US$50 per barrel US L48 production never gets much above where it is today.

That low-case scenario might seem to be no bad thing for OPEC and OPEC+ in one respect. A neutralised US tight oil sector would allow present constraints on OPEC+ production to be eased as oil demand recovers. This would help accommodate Libyan and, perhaps, even Iranian exports in the years to come. The flip side is the revenue challenge that US$50/bbl would present to a number of OPEC economies.

A sustained period of under-investment in non-OPEC supply also carries risks for the oil market. Global upstream spend has dipped to a 15-year low in 2020, with conventional investment hit as hard as tight oil. Our view is that the impact on future supply from the 2020 downturn will, in time, prove greater than it might on demand. This increases the chances of a supply squeeze and higher oil prices later this decade.