Did the oil and gas industry change forever last week?

Stakeholders intensify pressure on Big Oil to speed up action on climate

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Is net zero by 2050 at risk?

-

The Edge

Can emissions taxes decarbonise the LNG industry?

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

-

The Edge

Can carbon offsets deliver for oil and gas companies?

-

Featured

Wood Mackenzie 2023 Research Excellence Awards

-

The Edge

Nuclear’s massive net zero growth opportunity

Three discrete events, a taste of things to come: ExxonMobil and Chevron lost shareholder votes related to their strategy for climate change, while Shell lost a court case in the Netherlands that will require it to speed up its emissions reductions. I talked through the implications with Tom Ellacott and Erik Mielke of our Corporate Analysis team.

First, it was the Paris Agreement in 2016 that fired the starting gun for the oil and gas industry to tackle climate change, not last week’s announcements. Outside the Euro Majors and a handful of independents and NOCs though, progress so far has been pedestrian.

It’s been far too easy for much of the industry to kick the challenges of adapting to a low-carbon future into the long grass. Wood Mackenzie has advocated since Paris the need for all oil and gas companies to grasp the nettle.

The timeframe for change is accelerating, driven by investor pressures more than fundamentals.

These three events will trigger a domino effect through the wider sector with more stakeholder actions through courts and AGMs. No board, whether Major, NOC or independent, can now afford to dismiss the energy transition. The timeframe for change is accelerating, driven by investor pressures more than fundamentals.

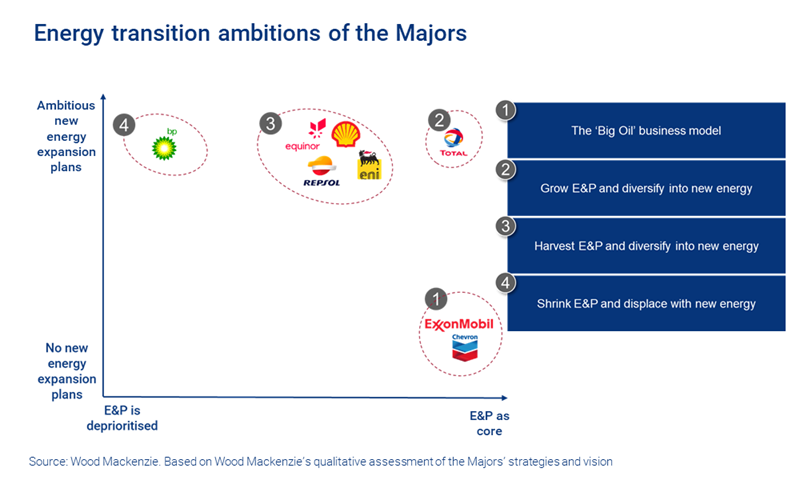

Second, the bare minimum isn’t enough anymore. ExxonMobil and Chevron need to pivot from followers into the vanguard of change. The big questions are how far and how fast do they move?

The Euro Majors are setting the pace, responding to evolving policy, societal mood and intensifying stakeholder pressure. Each company has outlined clear plans to cut Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions and achieve net zero for Scope 1 and 2 by 2050 at the very latest.

In contrast, the US Majors’ present targets are undemanding. ExxonMobil aims to cut Scope 1 and 2 emissions (upstream only) by 2025, Chevron by 2028. At the very least, we’d expect more aggressive targets for Scope 1 and 2 – the direct and indirect emissions from activities. These need to cover the whole business and not just upstream.

What’s more in question is whether the US Majors embrace Scope 3, the emissions released on combustion and which account for 85% of the total. Scope 3 targets would be a gamechanger that compromise the Big Oil strategy both US companies are pursuing. Such a commitment will not be taken lightly nor quickly.

ExxonMobil and Chevron’s staunch focus on oil and gas is reflected in our buoyant outlook for production – each company shows continuous growth for at least the next 10 years (ExxonMobil’s own ‘flat’ guidance to 2025 assumes disposals). Much of the new production is low cost and lower carbon (Guyana/Brazil/Permian tight oil for ExxonMobil, Permian tight oil for Chevron), which will reduce carbon intensity to a degree.

There’s a perfectly defensible argument that the world will need new supply over the next decade before electric vehicles and other transition technologies undermine demand. It’s a view that’s held by many investors and most oil and gas companies.

You just can’t do both – oil and gas production growth is incompatible with net-zero Scope 3 emissions without unfeasibly large-scale carbon offsetting. Most of the Euro Majors are dampening growth by reallocating capital away from upstream. BP, though, is out on its own, planning to cut production by 40% to meet its target to reduce absolute Scope 3 emissions by 35% to 40% by 2030. It’s already selling down assets.

Shrinking the upstream business would have to be a sizeable part of an eventual solution to reducing Scope 3 emissions for all the Majors, ExxonMobil and Chevron included. Low-margin refining capacity will also be surplus to requirements. It will come down to timing, and we don’t expect the US Majors to initiate radical downsizing anytime soon.

Moreover, the prospect of all the Majors selling significant chunks of upstream and downstream assets at some point in the future raises three big questions. Who will buy the assets? Where will the finance come from, given capital markets’ increasing reluctance to fund fossil fuels? And how will the emissions from these assets be stewarded in future? These are issues prospective sellers, and stakeholders, will face.

Third, should US Majors develop a clean energy business? The Euro Majors are all diversifying into Big Energy, investing in a wide range of low-carbon technologies to support a broader offering beyond the transition. The range of technologies includes renewables, CCS/CCUS, blue and green hydrogen and EV charging, as well as developing broader customer offerings.

ExxonMobil and Chevron’s primary low-carbon technology focus today is carbon capture and storage. It’s a proven technology in which they have competitive advantages. The problem is that CCS is a long-dated option on decarbonisation; it’s not commercial today and industrial-scale growth is a decade away. CCS will be an important part of the solution but far from the whole one.

Portfolio and technology optionality are a virtue, given the uncertainty of how energy markets will play out in the transition. The easy part is to be more ambitious on decarbonising upstream, eliminating routine flaring, minimising methane emissions through enhanced LDAR (leak detection and repair) and using wind and solar to electrify oil and gas production operations. The longer-term game would be to put risk capital into a broader sweep of technologies to hedge against the transition.

Sticking with Big Oil is a perfectly acceptable strategy. It’s just time-limited. If the goal is to be a big global energy provider in the low-carbon world of the future, US Majors need to build more optionality into the portfolio.