Libya: the two-million-barrel question

Challenges to Libya's ambitious crude production expansion plans

4 minute read

Martijn Murphy

Principal Analyst, North Africa Upstream

Martijn Murphy

Principal Analyst, North Africa Upstream

Latest articles by Martijn

-

Opinion

Middle East and North Africa upstream: 5 things to look for in 2024

-

Opinion

Libya: the two-million-barrel question

-

Opinion

Africa upstream oil and gas: one last hurrah?

Emma McRae

Research Analyst, Global Oil Supply

Emma McRae

Research Analyst, Global Oil Supply

Emma develops long and short-term liquid supply outlooks, mainly focusing on Europe and Africa.

Latest articles by Emma

View Emma McRae's full profileLibya aims to almost double its crude production levels over the next 3‒5 years, investing around US$ 4 billion a year. However, the country faces a myriad of obstacles, which will stump its plans.

In a recent report, entitled Can Libyan oil production reach 2 million b/d?, we evaluated Libya’s prospects of attracting international investment and achieving its output goals. Fill in the form for an abridged version of the report and read on for a brief outline.

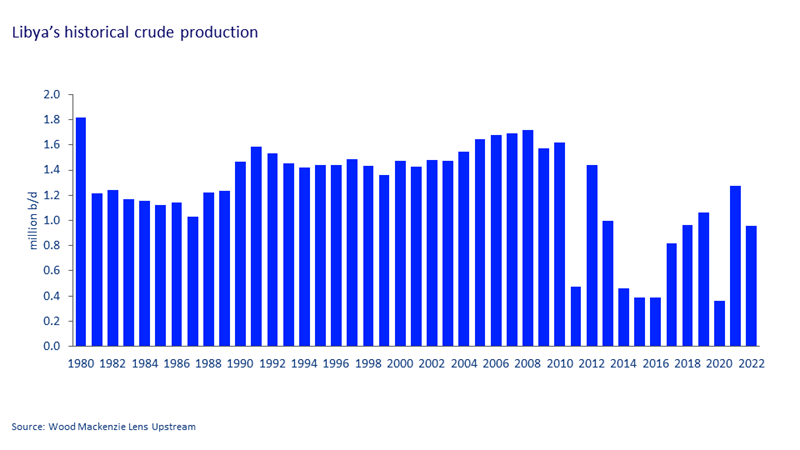

Producing 2 million barrels of crude oil per day is a long-standing Libyan goal and was often mooted by the Gaddafi regime in the 2000s. Yet, since the early 1980s, the country’s oil production has rarely eclipsed 1.7 million b/d and struggled to remain much above 1.2 million b/d since the 2011 civil war.

The most recent push stems from a change of leadership at Libyan National Oil Corporation (NOC), which is keen to keep the oil flowing and maximise state revenues. But Libya is also conscious of the energy transition and longer-term decline in demand for oil, especially from its key European markets. With investment harder to come by, it has deemed it better to raise capacity and entice investment by international oil companies (IOC) now.

Libya remains divided

This is far easier said than done. Libya has been divided since the civil war that followed the 2011 revolution. An internationally recognised administration, the Government of National Unity (GNU), governs in the west of the country, which was formed as part of a United Nations-led political process ahead of proposed elections in December 2021. However, the elections never took place and opponents now contest the GNU’s mandate to govern. A rival government in the east, the Government of National Stability, controls around three-quarters of the country’s oil production capacity. It was formed in March 2022 from a controversial vote by the House of Representatives after the 2021 electoral process collapsed.

With no elections in sight, the prospect of a durable political settlement that unifies both rival administrations remains distant. Neither side has the means, militarily or politically, to exert control over the entire country. A continuation of the status quo seems most likely in the medium term.

Shut-ins and ageing infrastructure threaten revival

Since 2011, shut-ins and blockades of fields, ports, pipelines and key infrastructure have been frequent, often achieving their aims. There has been some stability since July 2022, but shut-ins and the threat of them are never far away.

There is also continued risk from ageing infrastructure. Most facilities and pipelines are several decades old. Pipeline corrosion, leaks and well integrity issues present ongoing maintenance challenges. Onshore fields, many of which require artificial lift, have also suffered due to power outages. Multi-billion-dollar investment is required to overhaul ageing facilities and plants.

NOC’s investment targets won’t be met

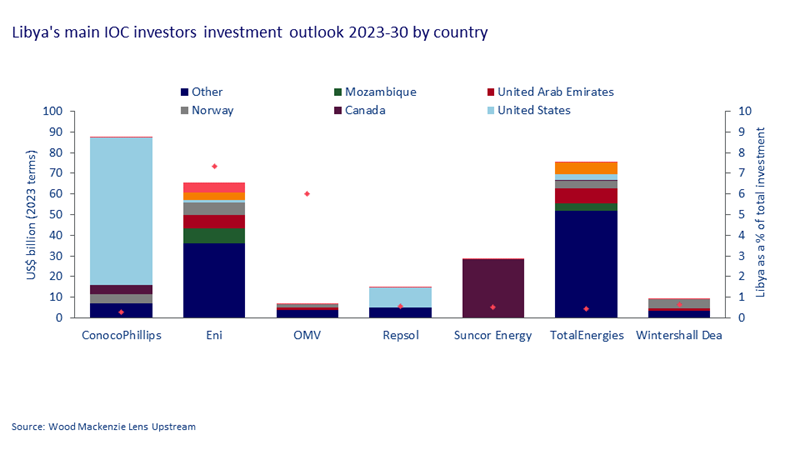

Libya has struggled to entice the requisite investment to grow its production. Since 2011, investment has averaged less than US$1 billion annually, hamstrung by NOC’s 50% share in most projects and its inability to meet its cash calls. Challenges accessing funds and budgetary uncertainty compromise large infrastructure developments in projects partnered by IOCs. Poor returns and long payback periods are further hindrances. IOCs are keener on lower-risk investments with shorter horizons.

NOC estimates that Libya will need about US$4 billion of investment a year to improve infrastructure and build oil production to 2 million b/d. We expect investment in onshore oil to increase over the coming years, but not to that extent. Libya remains peripheral to most incumbent IOCs investment plans. The exceptions are Eni and OMV, although investment in offshore gas accounts for most of Eni’s spending. For others, the focus will mostly be modest short-cycle projects aimed at incremental gains.

Exacerbating the situation are the country’s outdated fiscal terms. Licences were awarded under Exploration and Production Sharing Agreement terms (EPSA IV) in the 2000s, when Libya held more appeal and competition was fierce. NOC typically takes a large share of production ‒ 70% to 90% ‒ 'off the top'. Such a high margin leaves little revenue for operators to recover costs and make a return on their investment. Enhanced EPSA V contracts have been mooted but remain elusive.

Overall, we maintain a risked view of production in our base case. In this report, we explore both upside and downside scenarios (Fill in the form to learn more).

However, even in our high case we do not expect NOC’s target of 2 million b/d to be achieved. The spectre of oil production shut-ins continues to hang over Libya. And alongside outages from ageing infrastructure, investment will remain too low to achieve significant increases in the short to medium term.

If Libya can improve security and fiscal terms, then there is significant longer-term upside. Libya’s subsurface potential is not in doubt: with a huge low-cost resource base, and excellent prospectivity, investors are still interested in exploring and developing assets. Majors Eni and BP recently revoked their force majeure status on their exploration assets. And after a 16-year hiatus, a new oil and gas licensing round in 2024 may bring new investors. NOC is also considering offering marginal fields for IOC development. But terms must improve for meaningful investment to take off.