Playing by new rules: How the CBAM will change the world

September 2023

Authors

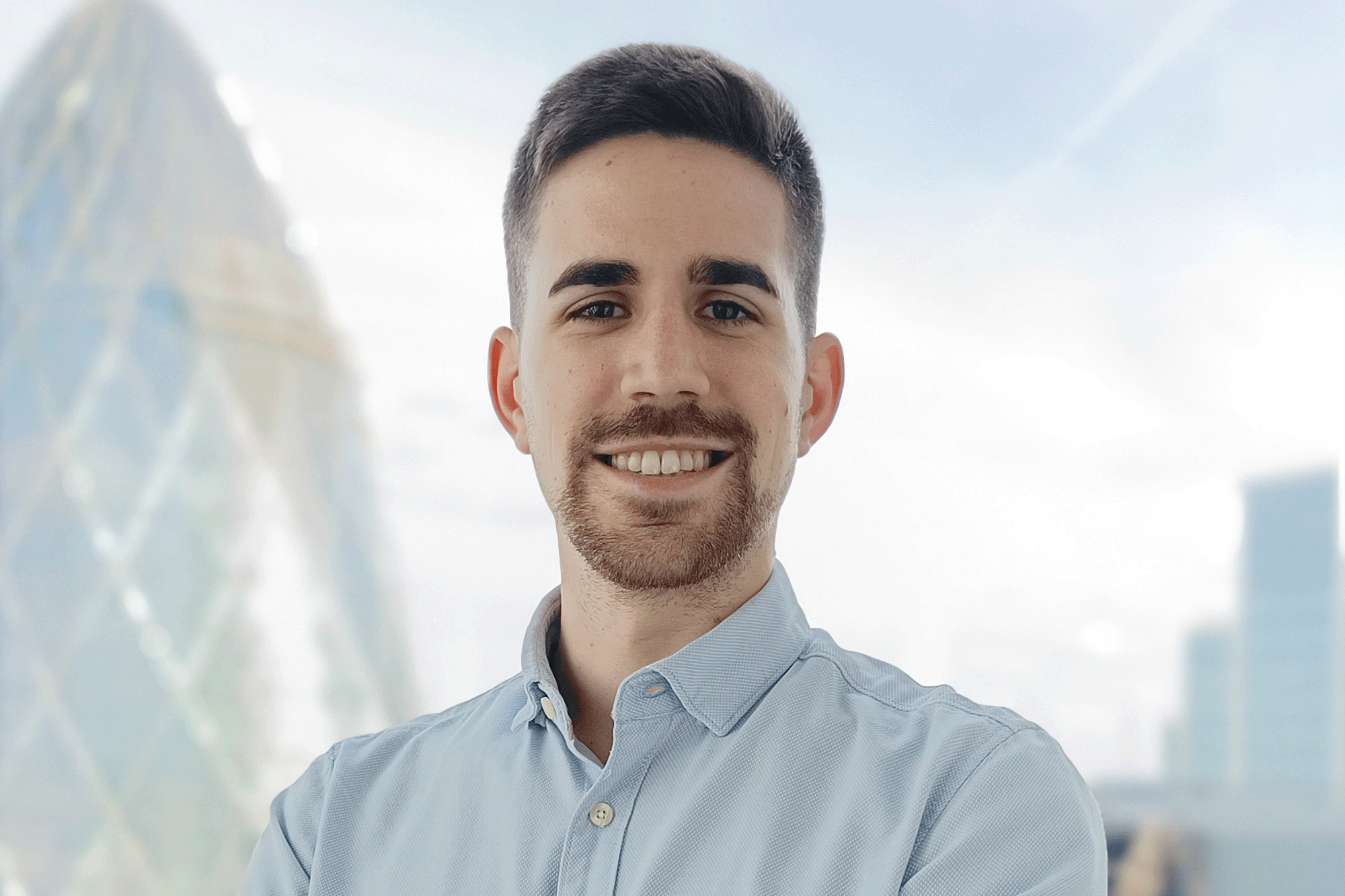

When the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is introduced in October 2023, importers of goods into the European Union (EU) will have to start reporting on the emissions embedded in their products. From 2026, they will have to start paying for them.

The CBAM, the first mechanism of its kind to be introduced anywhere in the world, aims to prevent EU producers, who have been paying a price for their emissions in the EU’s trading system, from being put at a competitive disadvantage to imports from countries where carbon is not priced. The consequences will be vast. The CBAM’s initial effect — over the next five years or more, depending on the sector — will be to reconfigure international trade flows. In the longer term, it will put pressure on other economies to cut their emissions.

As the CBAM is fully implemented, commodity and product prices in the EU are likely to rise. This should incentivise investment in carbon-reducing technologies in exporting countries, as low-carbon producers see opportunities to capture higher margins in the EU market.

Some countries may also start to introduce carbon prices of their own or to raise their existing prices. The CBAM is expected to generate more than US$9 billion a year in revenues from all targeted sectors by 2030. Part of that money will go into the coffers of EU member states, while part will be redistributed to low-income EU trading partners to incentivise decarbonisation initiatives. By following the EU’s lead and imposing a carbon price in their own jurisdictions, other countries can collect that revenue for themselves, rather than let the EU take it.

However, the CBAM has faced significant criticism from many sides. Countries such as China and India see it as a protectionist trade measure. Businesses and governments worry that its implementation will be imprecise, because of the complexity of verifying the emissions embedded in imports. And there are concerns about its effectiveness in actually encouraging low-carbon investment.

In this edition of Horizons, we explore the likely impacts of the CBAM as it is fully implemented over the coming decade and beyond. We focus on three representative value chains – steel, hydrogen and oil – to draw conclusions that will also apply to a range of other commodities and products.

Figure 1: CBAM in brief

EU producers will be affected too

Exporters into the EU will pay the CBAM based on the embedded emissions of the products they are selling, with a rebate for any carbon price that has already been paid in the country of origin. When it begins in October 2023, there will initially be no direct financial impact. Exporters to the EU will have to start reporting the emissions embedded in their products or face hefty fines of up to US$50/tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) if they fail to do so. The CBAM fee will be charged for the first time from January 2026, ramping up to its full level by 2034 for the initial sectors.

Producers in the EU have already been subject to a carbon price since 2005 under the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). However, to avoid disadvantaging trade-exposed commodities, they have been largely exempted from actual payments by being given free emissions allowances.

The CBAM will start with a few selected commodities to test the system and its global impacts. As it is ramped up and extended to more commodities and sectors, EU producers will lose their right to free emissions allowances, until both local producers and importers pay a full carbon price on their emissions.

Over time, the CBAM will establish carbon as a new cost factor in international trade. The cost will be significant: the CBAM price will be the same as the allowance in the EU ETS, which traded above US$100/tonne CO2e for most of 2023 – around four times the global average cost of carbon.

A shift in global steel trade patterns

Iron and steel are very energy- and carbon-intensive commodities to produce, accounting for nearly 6% of the EU’s total emissions. They will be among the first sectors covered by the CBAM, corresponding to about 4% of the EU’s total imports by value.

The CBAM and the loss of free allowances for domestic producers in the EU ETS will push up steel costs and prices in the European market. Both domestic and foreign steel producers selling in the EU will face greater pressure to invest in higher-cost low-emission technologies, such as carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), hydrogen and increased energy efficiency.

For steelmakers in the EU, production will become more expensive.

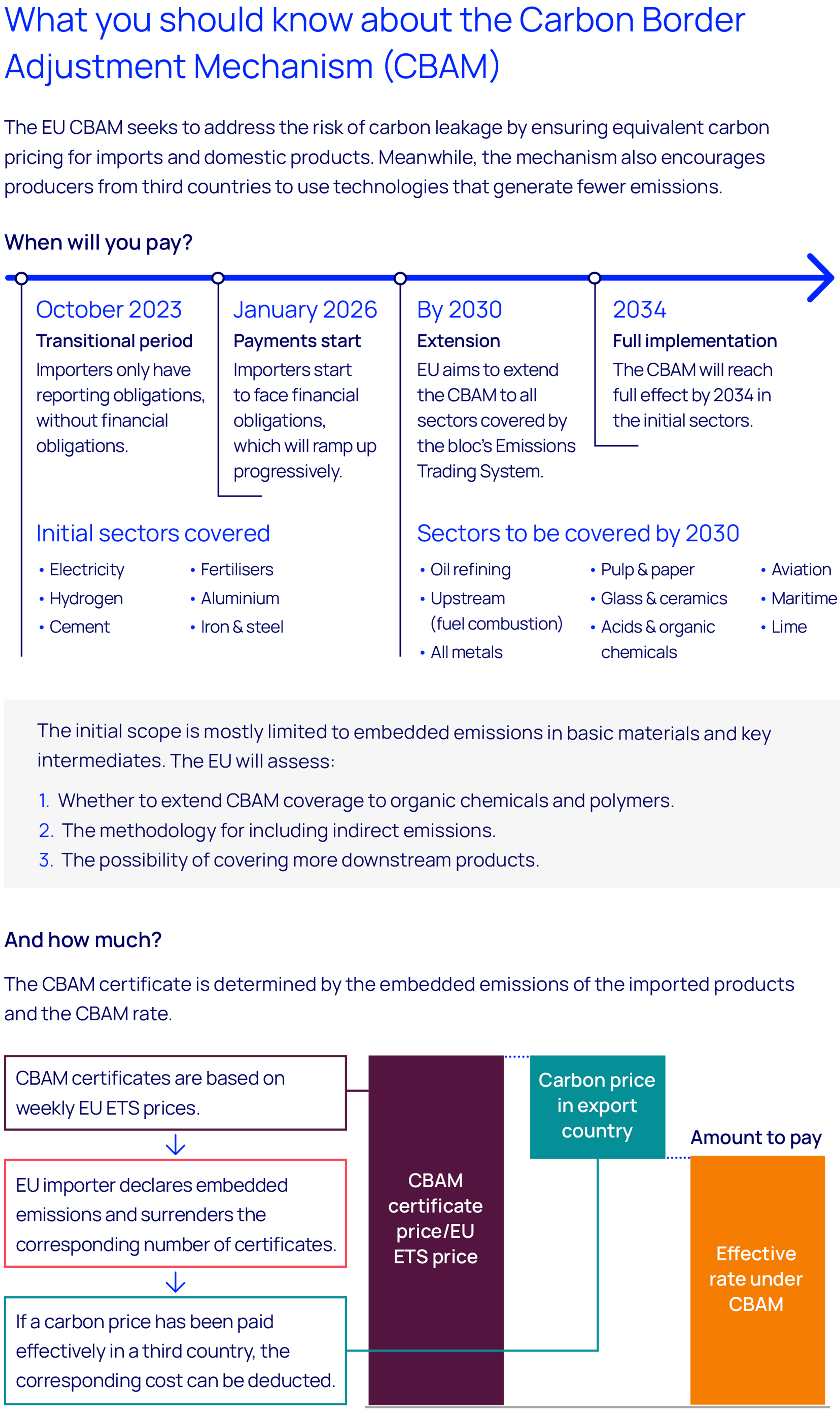

For exporters, one initial response is likely to be a reorganisation of sales to direct lower-emissions steel to the European market, while higher-emissions production is diverted to markets without carbon fees. The EU plans to monitor and address these strategies, but it does not have a concrete action plan to prevent them.

As the CBAM moves to full implementation in 2034, it will gradually increase the incentive for exporters to invest in emissions reduction technology so they can sell more into the EU.

Figure 2: Which exporting countries will feel the pain?

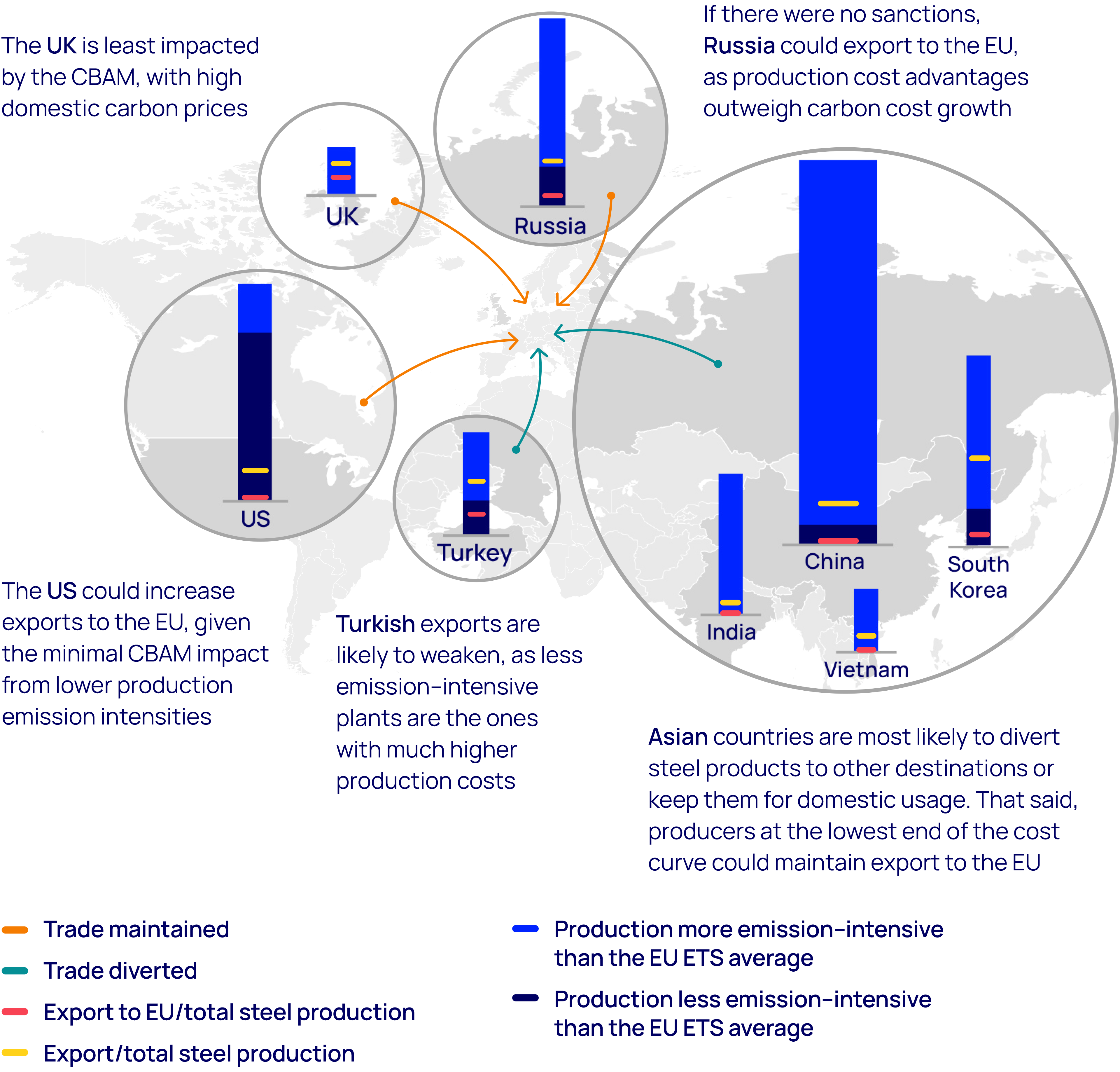

Wood Mackenzie estimates that by the end of the phase-in period, the cost of the CBAM for some of the key exporters to the EU could exceed US$275/tonne of finished steel. For reference, in 2022, the average import price of steel products covered by the CBAM was around US$1,450/tonne. The CBAM fees could increase the cost of delivered steel to the EU by about 56% for India and about 49% for China in 2034.

Figure 3: CBAM-induced increase in the cost of delivered steel to the EU by 2034

In the early stages of CBAM implementation, higher prices in the EU will enable some low-cost foreign producers to maintain exports to Europe. Over time, however, the growing carbon cost will erode the competitive advantage of many non-EU producers, making the EU a less economically attractive export destination for higher-emitting steelmakers.

Carbon will be a new and increasingly important cost component of international trade. Initially, the CBAM will cover only raw materials and simple goods. But we expect that, as the policy evolves, more downstream products and finished goods will be covered.

Collateral damage should be expected, not only in the higher costs that will be inevitably passed on to European end-users, but also in the additional strains on industrial supply chains. The widespread use of steel products across a broad range of technologies in the energy sector, including wind turbines and electric vehicles, puts them at the centre of the transitioning world. The CBAM is intended to ensure a fair transition in the EU and globally, but an unintended consequence could be to make the transition in Europe more expensive than elsewhere. In a high-price environment, an additional cost could result in political backlash.

Sizeable opportunities in the low-carbon hydrogen trade

Growing EU demand will push the global hydrogen and ammonia industries to decarbonise. Through its REPowerEU targets, by 2030, the EU aims to produce 10 million tonnes and import 10 million tonnes of hydrogen produced using renewable energy each year. The CBAM will put an additional incentive in place and stimulate imports of low-carbon hydrogen and its derivatives. Carbon-intensive hydrogen and derivatives from countries with low-cost feedstock may still remain competitive into the EU, but grey hydrogen will likely be increasingly diverted to other markets.

Ammonia and fertilisers will be central to low-carbon hydrogen strategies. Ammonia is used as a hydrogen carrier, as it has a higher volumetric energy density than liquid hydrogen – meaning more energy can be transported via ammonia for the same volume than in the form of liquid hydrogen – and has some transportation and storage infrastructure already in place. We expect traditional ammonia to be the largest consumer of low-carbon hydrogen until the mid-2030s, when power will become the top offtake sector. Fertilisers are currently the largest end-use for ammonia and are likely to remain so until 2050 at least.

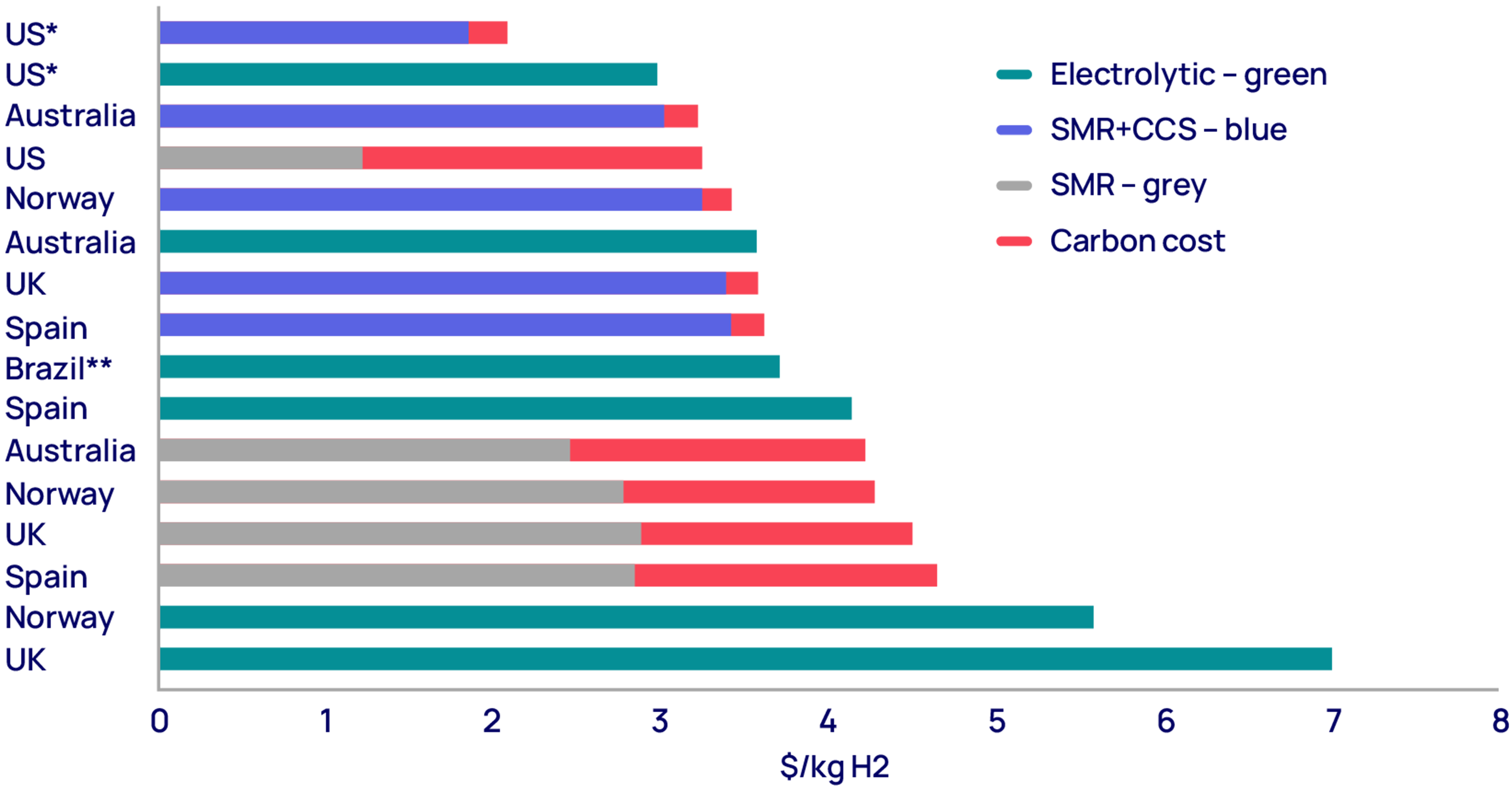

With the CBAM being phased in and EU ETS free allowances being phased out, grey hydrogen will no longer be the most economically attractive production process. As carbon costs rise, grey hydrogen will eventually become more expensive in terms of levelised cost of hydrogen (LCOH) than the two key low-carbon technologies: green hydrogen, produced by electrolysing water, and blue hydrogen, produced from natural gas with carbon capture. Producers both inside and outside the EU will be forced to look for lower-emission routes for producing hydrogen. The following chart shows the countries that we expect to be major hydrogen producers in 2036 and the cost by process.

Figure 4: LCOH and carbon cost by country, 2036

Europe’s gas price crisis, fuelled by Russia’s war on Ukraine, has challenged the economics of blue hydrogen projects (see Horizons – Stick or twist: should gas resource holders target LNG exports or blue ammonia?). By 2036, however, we expect blue hydrogen to be the most competitive technology from a range of non-EU sources, including the US and Australia.

The cost effect of the CBAM on blue hydrogen will be relatively minor, at less than 20 US cents per kilogram, as CCUS can trap over 90% of carbon emitted from point sources. The cost of capturing carbon from hydrogen plants is also relatively competitive and is likely to drop below US$50/tonne in the next decade.

In the 2040s, as technology matures and renewable power becomes less expensive, the LCOH for green hydrogen is likely to continue to decrease and become as competitive as that for blue.

In the ammonia market, gigawatt-scale projects targeting exports from leading renewable energy producers (Australia, Norway and the Middle East) will emerge by the 2030s, driving a major shift in trade flows. Markets such as the EU, which are targeting decarbonisation and depend on ammonia imports, will eventually push for low-carbon domestic supply. However, there will be a transition period in which the EU is likely to remain dependent on imports and will buy low-carbon ammonia from the most competitive suppliers, such as the US.

The CBAM could have unintended consequences in some sectors including fertilisers, and lead to a political backlash. Fertiliser demand is very price sensitive. In 2022, when soaring natural gas prices drove up the cost of fertilisers, farmers reduced their use, hitting crop yields and reducing food supply. In a similar way, the CBAM could unintentionally lead to higher domestic food prices, unless the EU puts in place the right safeguards or incentives to invest in new, more advanced decarbonisation technologies for hydrogen production. For example, the EU could emulate the US Inflation Reduction Act’s 45V production tax credit to give a significant boost to low-carbon hydrogen production.

Oil producers and refiners have strategic choices to make

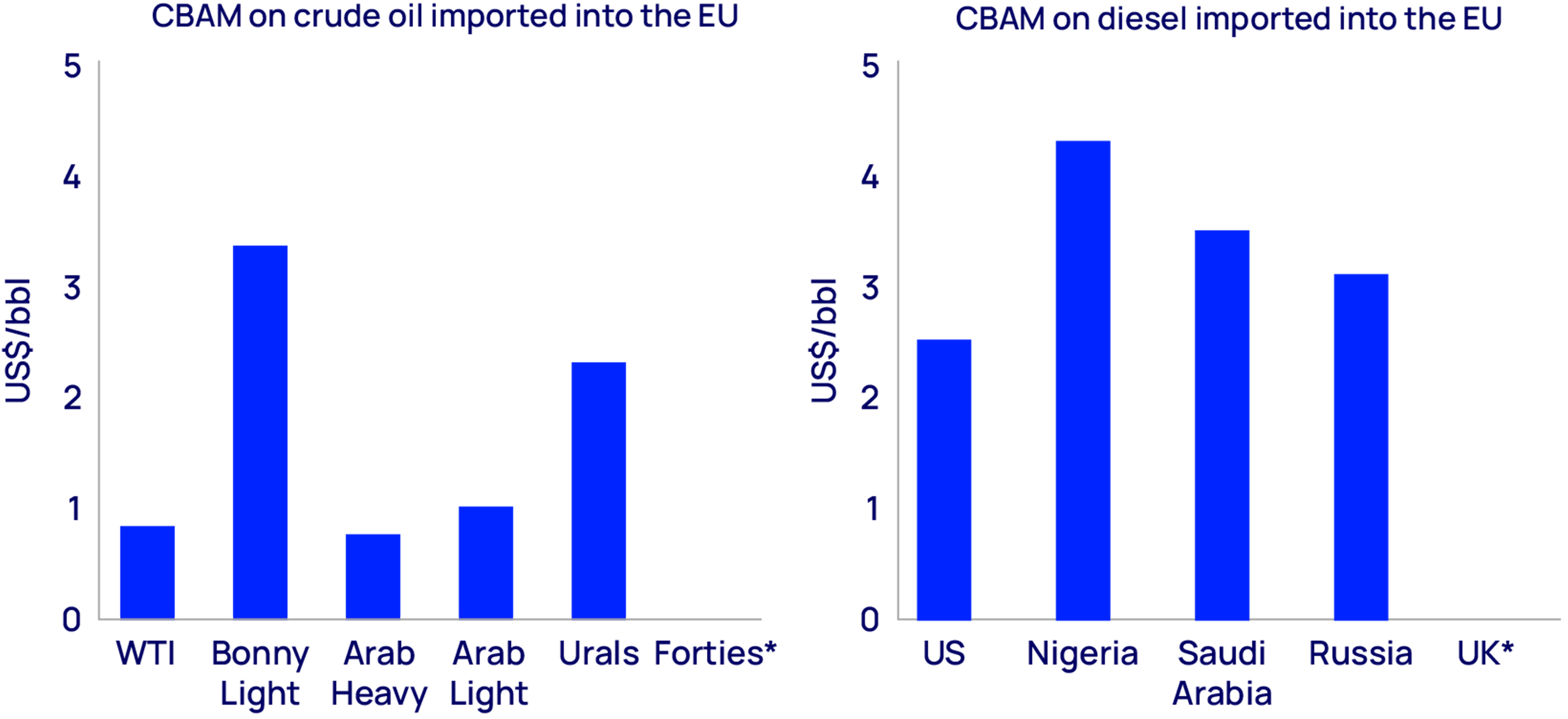

While the oils value chain is not one of the initial sectors covered by the CBAM, Wood Mackenzie expects oil production and refining to be included in 2028 and fully covered by 2036.

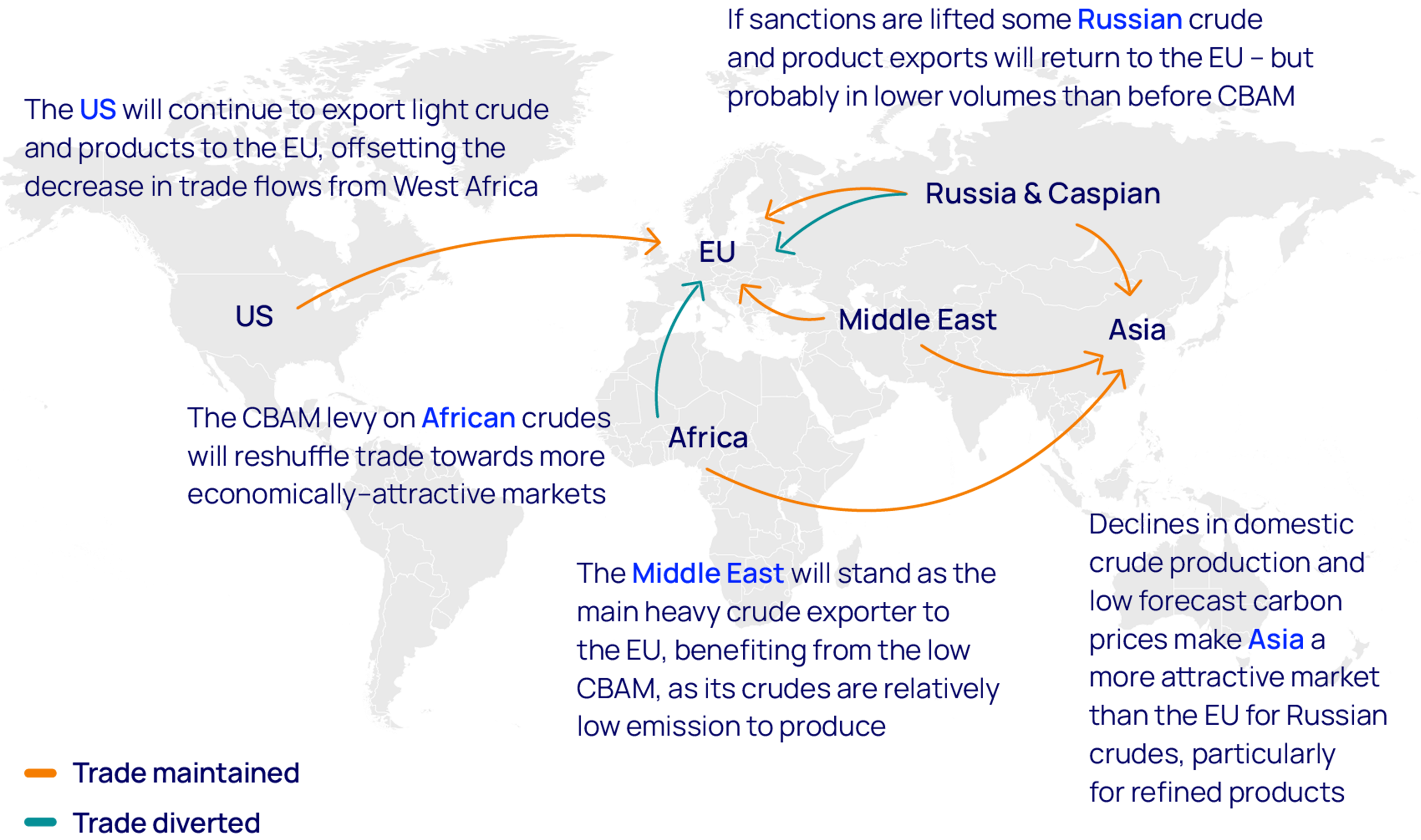

The crude oil and refined products markets are highly liquid, so trade patterns respond swiftly to changes in cost structure. We expect that total net imports of crude and middle distillate into the EU will not be jeopardised by CBAM implementation. But some trade flows will change, depending on carbon intensity and domestic carbon pricing of exporting countries.

The CBAM will increase the cost of doing business in the EU by stacking up carbon charges along the oil value chain. EU refiners will face increased feedstock costs. European crude production, which typically has lower embedded emissions, is unlikely to increase sufficiently to meet the EU’s needs. EU refiners will also have to pay for the EU ETS on their own emissions.

The costs of imported crude and wholesale refined products will increase as the CBAM tariff is passed onto EU consumers. Full CBAM implementation could boost crude and refined product prices by up to US$5/barrel, adding 30 euro cents per litre to costs at the pump.

One potential impact of the CBAM will be on Russia’s crude exports. Such imports into the EU are currently blocked by sanctions imposed after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But even if the sanctions are lifted, the CBAM could restrict those exports. These Russian crudes are quite emissions-intensive to produce, meaning they would face relatively high CBAM costs, which could support continuing long-haul exports to Asia rather than the shorter journey to Europe.

Crudes with low emission intensities could increase their market share in the EU. For example, the CBAM would increase the cost of the US West Texas Intermediate and Middle Eastern crudes by less than US$1/bbl, making them competitive against regions with more carbon-intensive production processes, such as West Africa and Russia.

Figure 5: Which oil producers are likely to be hit by the CBAM?

The EU will remain an attractive market for those investing in carbon abatement technologies and for crudes that generate fewer emissions during the production process. Optionality will be an advantage for exporters. For example, Middle Eastern producers will look to maximise the value of their crude, which has relatively low production emissions, in the EU market. In contrast, their distillate exports, which have relatively high production emissions, will target other deficit markets, such as Latin America and Africa.

How will global oil flows shift after CBAM?

Explore our latest thinking in Horizons

Loading...

Sign up now to get insights like this in your inbox weekly.

Our unique point of view on the latest news, tailored to your industry and interests.