Indonesian nickel ore ban: who will fill the supply gap?

The expedited ban has significant implications for the whole industry, with a particular supply challenge for Chinese nickel pig iron (NPI) production.

1 minute read

On 30 August 2019 the Indonesian government announced that a ban on nickel ore exports would come into effect on 1 January 2020 – two years ahead of its planned date.

The news caused an immediate price spike. And while this retreated as the market took a more measured view of the nickel outlook, there is little doubt that the ban will have significant implications for NPI supply in the coming years.

Let’s look at some of the immediate questions resulting from the expedited ban.

Why was Indonesia’s nickel ore ban brought forward?

We see two main drivers shifting the ban forward:

- The export ban will help to preserve Indonesia’s nickel ore resource base for its rapidly growing NPI and stainless steel melting industries.

- The ban was put in place following Indonesia’s relaxation of a previous ore export ban in 2017, which only allowed nickel ore export of a grade below 1.7%. The recent development of new high pressure acid leach (HPAL) projects means Indonesia can now process lower grade ore domestically, with a view to meeting electric vehicle (EV) battery raw material demand.

How much nickel ore supply will be lost?

China is the primary importer of Indonesian ore. We estimate that Indonesia will supply around 350 kt of nickel to China in 2019, around 40% of its total ore imports.

We don’t expect a ‘hard stop’ in January 2020 as the ban comes into effect. Instead, we anticipate that around 80 kt will flow into China from nickel ore dispatched in December 2019 – a similar level to what was seen after the first export ban in 2014.

Nonetheless, this is a significant drop in feed supply to Chinese NPI smelters, which will limit production.

Can other countries fill the nickel ore gap?

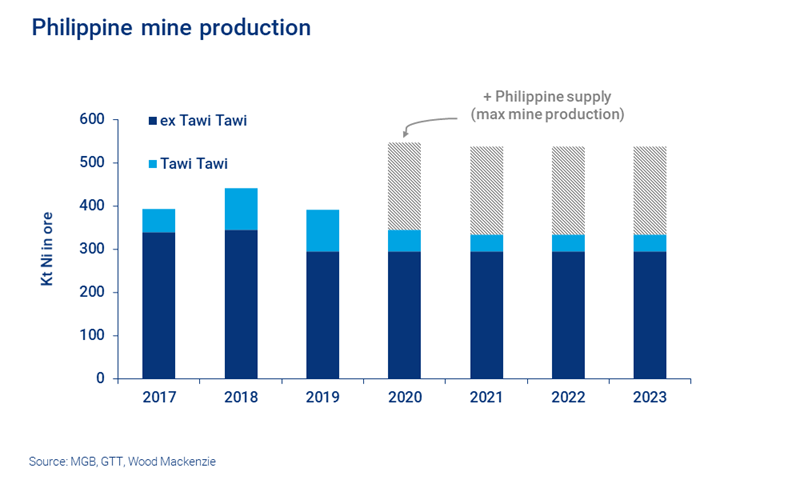

The Philippines is typically viewed as the main potential source of additional ore. When the first ore export ban was put in place in 2014, the Philippines significantly raised its exports to China. This was mainly achieved through increased production from mines in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), and in particular from Tawi-Tawi. As it stands, we expect Philippine exports to remain at 295 kt from 2020 onwards – excluding the Tawi-Tawi region.

Tawi-Tawi shipped around 96 kt Ni in ore to China in 2018, and year-to-date data indicates a similar level in 2019. You can read an overview of our forecast for this region in our recent insight.

The Philippines is not the only ore-exporting country, of course. New Caledonia, for example, is ramping up its exports to 4 Mwt from 1.57 Mwt in 2018. However, New Caledonia, along with Guatemala, Turkey and Albania, are comparatively small suppliers.

A higher ore price would, in theory, encourage miners across these countries to increase production. Based on each individual mine’s optimal production record in the past five years, this could add an upside potential of around 200 kt. However, in our view legislative and environmental restrictions make this unlikely.

We don’t believe that mine production in the Philippines and other ore-exporting countries can increase to a level that could offset the impending loss from Indonesia.

What does this mean for Chinese NPI production?

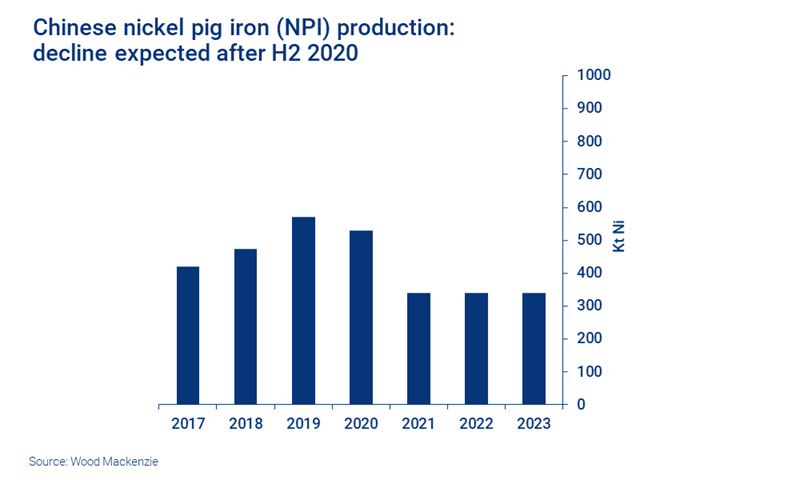

Chinese NPI production in 2019 will not be disrupted by the ore ban – we maintain our forecast at 570 kt Ni. But while current ore stockpiles provide a temporary cushion, we do expect to see cutbacks in Chinese NPI production from H2 2020.

And as Chinese NPI production declines, Indonesian NPI is ramping up. We expect Indonesian NPI output to achieve 36% year on year growth in 2019, reaching 360 kt Ni.

To find out more about how Indonesia will scale up production and the landscape of global NPI supply, read our report: How will the Indonesian ore ban impact NPI supply

Interested in trends affecting nickel?

Find out more about the outlook for nickel in Metals & mining: what to look out for in 2021. This report includes insight into decarbonisation and its impact on the sector, along with commodity-level insight for base metals, gold, iron ore and coal.