Can Asia avert a gas supply crisis?

With domestic supply in decline, Asia urgently needs to address its growing gas and energy needs

1 minute read

Angus Rodger

Vice President, SME Upstream APAC & Middle East

Angus Rodger

Vice President, SME Upstream APAC & Middle East

Angus leads our benchmark analysis of global Pre-FID delays, and deep water developments.

View Angus Rodger's full profileIn the past few months, energy crunches across the globe have served as a stark warning of the critical need for flexible and reliable supplies of energy. In Asia, a growing gap between booming gas demand and falling supply is cause for significant concern.

We recently completed a piece of detailed, cross-functional research on the issue. This draws on insight from Lens, our industry standard data and analytics tool, as well as expertise from across our gas & LNG and power & renewables teams for the APAC region. Fill in the form to get access to the report. Or read on for a quick introduction to the topic.

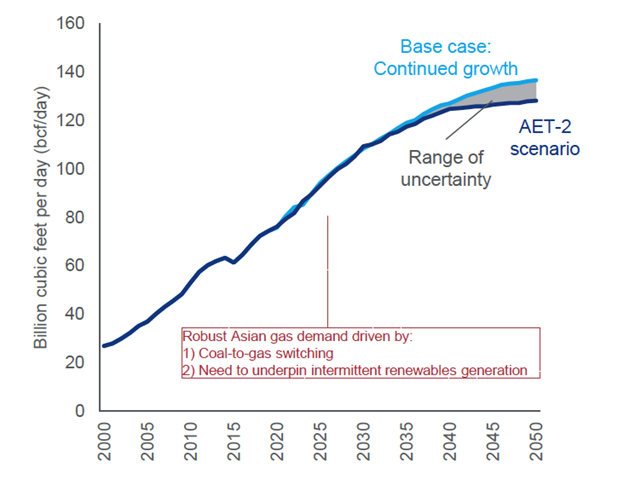

The Asia gas growth story: positive, powerful, and resilient

Under our base-case scenario, Asian gas demand will almost double by 2050 to around 140 billion cubic feet per day. Even under our Accelerated Energy Transition Scenario (AET-2), whereby global temperature rises are limited to 2° C, we expect demand to be almost as strong. This robust demand will be driven by coal-to-gas switching as well as a need to underpin intermittent renewables generation. Unless domestic gas production can be ramped up, the demand for imported LNG in the region will continue to rise.

Asian gas demand, Wood Mac base case versus AET-2 scenario

Source: Wood Mackenzie Energy Transition Service. Asian gas demand includes North Asia (Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, China), South East Asia (Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos) and Southern Asia (India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh).

Unfortunately, domestic gas production is falling

Asia is not short of gas resources, but it lacks commercially attractive opportunities. In terms of discovered resources, while 61 billion barrel of oil equivalent (boe) is already onstream, another 56 billion boe is discovered but considered non-commercial. The vast majority of these resources, over 70%, is gas.

And while some mature gas fields are enjoying a short-term rise in output thanks to higher prices and post-pandemic demand, deferred maintenance and development programmes could cause problems in the future. What’s more, 25 trillion cubic feet worth of projects awaiting a final investment decision are struggling to progress, and overall capex spend and exploration activity are both falling. Given all these factors, our base-case upstream outlook for the region is gloomy, with only China set to increase output, and that only in the near term.

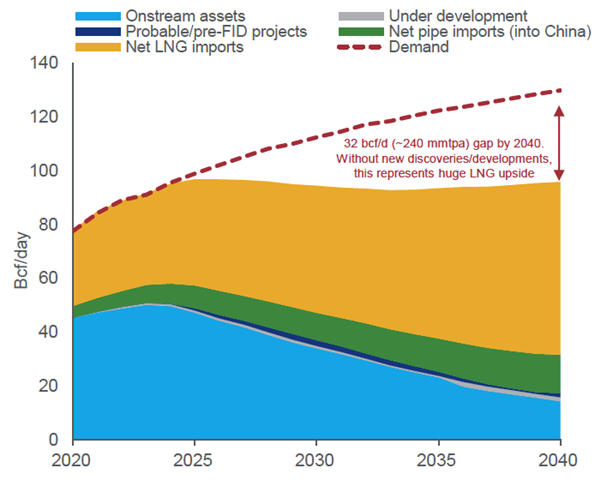

Reliance on imported LNG will increase in the short term

As a result of these factors, our base case forecasts a rapid rise in LNG imports into Asia. if More new discoveries and developments are needed to slow the rising rate of LNG dependency But if that fails to happen, and gas output falls faster than expected, even more imported LNG will be needed — up to 240 million tonnes per year more by our estimates. Taking South East Asia as an example, if exploration ceases to contribute, regional reliance on imported LNG will jump from 61% to 83% by 2035.

Asia’s gas supply/demand balance to 2040

Source: Wood Mackenzie. *Includes Southern Asia, South East Asia and North Asia/China

Longer term solutions are required

Recent global gas price hikes highlight how security of supply cannot be taken for granted. In short, governments across Asia need to address potential overreliance on imported LNG, which carries significant price risk. In 2021, some South Asian countries were paying up to US$40/mmbtu to import spot LNG cargoes to meet their energy needs. That is not an attractive or viable situation to be in. Ramping up renewables is a partial solution, but intermittent supply will remain an issue until effective energy storage solutions are available at scale. Prioritising the development of domestic gas resources therefore seems highly desirable. The other option is to increase reliance on coal, which will make climate goals even harder to achieve.

Fiscal policies will be critical

To solve the problem, flexible fiscal policies will be critical. Most upstream fiscal regimes in Asia have been in place for decades, and need updating to be fit-for-purpose for the energy transition. Governments need to have a clear end goal in mind and ask themselves difficult questions. Should remaining upstream value be harvested, or is there a need to incentivise new investment?

Previous upcycles resulted in more upstream spend, but the energy transition has changed the rules. International oil companies are less keen to develop Asia’s large but ‘dirty’ gas resources and national oil companies cannot do it all by themselves. Fiscal incentives are therefore needed to help cover the cost of decarbonising upstream extraction.

The alternative is be to expedite the energy transition. Or can a holistic approach achieve all these goals and offer the best chance of success? There is no ‘right’ approach here, the only wrong answer is for a government to not know what its fiscal terms are designed to achieve in a rapidly-changing world.

Those who take a ‘do-nothing’ approach may be forced to fall back on coal to fill the energy supply gap. Given the direction of travel in global climate policy, that’s likely to create its own problems. With that in mind, governments need to address these questions urgently.

Don’t forget to fill in the form at the top of the page to access more in-depth analysis of the outlook for Asian gas. As well as detailed forecasting and analysis of the risks to supply, this includes a full breakdown of the upside and downside risks to Asia gas demand.