Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Rethinking energy security

The transition to low-carbon sources creates a new set of concerns about excessive dependence on imports

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

What the "big beautiful bill" means for US energy

-

Opinion

Inside the ‘crazy grid’

-

Opinion

The Big Beautiful Bill is close to passing

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

Winston Churchill famously held that the key to energy security was diversity in sources of supply. “Safety and certainty in oil lie in variety and variety alone,” he told Parliament in 1913. It is an argument that has been brought back into sharp focus this year, as sanctions imposed on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine have been constrained by the world’s reliance on its oil, gas and coal.

The crisis is also prompting a more general look at energy security. While it is fossil fuels that are the key issue with Russia, there are also questions being raised about energy consuming countries’ reliance on imports for key low-carbon technologies and commodities including solar panels and battery raw materials. Russia creates huge energy security issues because it accounts for about 11% of the world’s oil supply and about 35% of Europe’s gas supply. But those market shares are modest compared to China’s 66% of global manufacturing capacity for solar modules, and 88% of global manufacturing capacity for batteries for electric vehicles and storage.

The two situations are not identical. If a country is cut off from its sources of oil and gas, it will quickly grind to a halt. If it is cut off from its sources of solar panels and batteries, its existing installed base will still be usable. But some governments around the world are already thinking about the security implications of relying heavily on imports for the commodities and technologies needed for the transition to low-carbon energy. Last week, the Biden administration announced two moves that could help to address those vulnerabilities.

On Thursday, the White House invoked the 1950 Defense Production Act, with the aim of strengthening domestic supplies of battery raw materials including lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, and manganese. President Joe Biden’s executive order announcing the move argues that “action to expand the domestic production capabilities for such strategic and critical materials is necessary to avert an industrial resource or critical technology item shortfall that would severely impair the national defense capability.” Soaring prices for battery raw materials, driving up the cost of electric vehicles, have highlighted those risks.

The order mandates the Secretary of Defense to help increase domestic production for these critical materials by supporting a range of activities, including feasibility studies for new mining and processing projects, and modernisation to increase productivity at existing facilities.

The DPA was used dozens of times during 2020-21, as the Trump and then Biden administrations attempted to increase production of urgently needed medical supplies including Covid tests and personal protective equipment. Those actions do seem to have helped make critical supplies available, even though the process was not perfect.

Some companies in the battery and electric vehicle value chain welcomed the president’s announcement. Others urged the administration to do more to secure supplies of battery raw materials, possibly through financial aid for producers, or by streamlining permitting to make it easier to set up or expand mines and processing facilities. Doing more to boost domestic production of critical minerals has bipartisan support in Congress, and it is possible that legislation offering some of that extra help to producers could be passed this year.

New tariff threat for US solar imports

Another move last week intended to strengthen the US supply chain for low-carbon energy was the announcement by the Department of Commerce of an inquiry into imports of solar cells and modules, which could lead to additional duties being imposed. The inquiry will look at whether crystalline silicon photovoltaic cells and modules that are completed in Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, or Vietnam, using components from China, are circumventing antidumping and countervailing duties imposed with the aim of stopping unfair competition from Chinese manufacturers. The inquiry, which was launched in response to a petition from a company called Auxin Solar, a US-based solar module manufacturer, could result in additional duties being imposed on imports from those four countries.

Some of the news reports about the announcement highlighted the fact that the highest rate of duty that could be imposed is 250%. That is the highest rate only for companies that do not cooperate with the investigation, however, and all the large manufacturers have engaged with the Department of Commerce. If additional duties are imposed on those companies’ products, they would probably be in line with the range from previous cases, which is 18-27%, although the outcome is still highly uncertain.

Imposing new duties at around that level would mean a significant increase in the cost of solar power in the US, at a time when costs for inputs including steel and polysilicon have already been rising, says Xiaojing Sun, Wood Mackenzie’s head of solar. It would also have a significant impact on solar installations in the US.

Since 2012, when the US first levied additional duties on imports of solar cells from China, there has been a dramatic shift in the pattern of trade. US solar imports from China have plummeted, while its imports from Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia, the four countries covered in the investigation, have soared.

If new duties are imposed on those imports and they become uncompetitive in the US market, the modules available from other sources, including US manufacturers, are unlikely to be enough to meet demand.

Abigail Ross Hopper, president of the Solar Energy Industries Association, described the commerce department’s investigation as a “misstep” that would have a devastating impact on the US solar market. She added: “The solar industry is still reeling from a similar tariff petition that surfaced last year. The mere threat of tariffs altered the industry’s growth trajectory and is one of the reasons why we’re now expecting a 19% decline in near-term solar forecasts.”

The issue is a stark illustration of why the global trading system should not be counted out just yet, despite all the strain it has been under in recent years. President Biden is determined to build up the US manufacturing base in low-carbon energy. It is one of his signature issues. His administration has worked to make progress on it with a series of policy initiatives, including the bonus tax credits for renewables projects with domestic content above certain thresholds that were included in the Build Back Better legislation that failed to pass in Congress last year.

The problem is that domestically produced equipment may often be higher-cost than the imports it is intended to replace, and may jeopardise renewable energy project economics. Onshoring can reduce risks in the supply chain. But it is an insurance policy that comes with a price tag.

Opening the floodgates on the Strategic Petroleum Reserve

Thanks to the tight oil boom, the US has stopped being a large petroleum importer. Its trade in crude and refined products is roughly in balance, and likely to remain so for the next few years at least. So the need to maintain a large Strategic Petroleum Reserve, at broadly the same level since 1990, has increasingly been called into question. There are nuances around crude quality and pipeline infrastructure, but essentially the point stands: the need for the US to maintain a large government oil reserve has faded over the past two decades. Now the Biden administration has come up with a solution for what to do with that (arguably) superfluous oil: sell some of it to ease the pressure on gasoline prices in the run-up to the midterm elections in November

The administration last week announced what it is calling “the largest release of oil reserves in history”: a plan to put an extra 1 million barrels per day on the market, on average, every day for the next six months. If the plan is carried out in full, it will mean selling off about a third of all the oil currently held in the SPR. President Biden described the plan as “a wartime bridge to increase oil supply until [US] production ramps up later this year.” By the autumn, he suggested, US oil production could be 1m b/d higher than it is today.

The Department of Energy plans to use the revenue from the sales to restock the reserves “in future years”. The administration says promising to buy oil will provide a signal of future demand, which it hopes will encourage oil companies to increase production faster.

While announcing his plan, President Biden criticised the oil companies that are being cautious about ramping up production. “I say: Enough. Enough of lavishing excessive profits on investors and payouts and buybacks when the American people are watching, the world is watching,” he said.

“It’s time to step up for the good of your country, the good of the world; to invest in immediate production that we need to respond to Vladimir Putin; to provide some relief for your customers, not investors and executives.”

The American Petroleum Institute, the industry group, put the ball back in President Biden’s court, saying the SPR release was not a long-term solution. Frank Macchiarola, a senior vice-president at the API, said: “Instead of managing from crisis to crisis, we should be focused on promoting policies that avoid them altogether through increased production of our nation’s domestic energy resources.”

In the short-term, the SPR release plan does seem to be helping to cool the oil market a bit. Brent crude ended the week at about $104 a barrel.

In brief

The OPEC+ countries held their latest regular monthly meeting, by videoconference as usual, and agreed to increase production by 432,000 barrels per day in May. That is a slightly larger increase than the 400,000 b/d rise each month that the OPEC+ group set as a plan last year, as a way to continue the steady unwinding of the emergency production cuts it made in 2020.

In their statement, the group’s ministers said the outlook pointed to “a well-balanced market” for oil, and that current volatility was not caused by fundamentals, but by ongoing geopolitical developments.

OPEC ministers also agreed to stop using the International Energy Agency as a secondary source for its member countries’ oil production, and to start using Wood Mackenzie as one of those sources.

Other views

Simon Flowers — Five ways the Russia/Ukraine war is changing oil markets

Raphael Portela and Kavita Jadhav — How are global NOCs tackling the energy transition?

Julie Wilson — Climbing the oil and gas ladder: four lessons from women in exploration leadership

Class of 2022: benchmarking this year's upstream FIDs

Matthew Yglesias — How natural gas powers renewables

Quote of the week

“From this month on — no more Russian gas in Lithuania. Years ago my country made decisions that today allow us with no pain to break energy ties with the aggressor. If we can do it, the rest of Europe can do it too!” — Gitanas Nauseda, president of Lithuania, announced that his country would soon stop importing any Russian gas to meet domestic needs, and urged his fellow EU leaders to put in place policies that would allow them to do the same. Lithuania has had the Independence floating LNG storage and regas terminal operational at the port of Klaipeda since early 2015.

Chart of the week

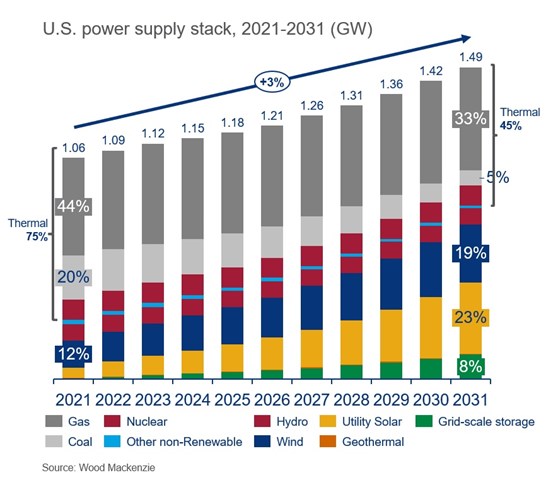

This comes from a presentation on trends in the US energy storage market, given last week by Vanessa Witte, Wood Mackenzie’s senior analyst for storage, at the Solar Energy Industries Association’s Finance, Tax and Buyers’ Seminar in New York. It shows Wood Mackenzie’s base case forecast for how the US power supply mix is expected to evolve over the coming decade, with rapid growth in wind, solar and storage. By 2031, we expect just 45% of US power supply capacity to be in thermal (gas, coal and nuclear) sources, down from 75% in 2021. That shift creates a greatly expanded need for storage.