Future energy – how electric vehicles transform battery demand

Risks to future supply of lithium, cobalt and nickel

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

Batteries play a big part in the energy transition. That’s reflected in the price of battery raw materials, including cobalt, nickel and lithium, all of which are rising on the tide of the present commodity rally. Our expert on battery raw materials, Gavin Montgomery, Research Director, talked me through the outlook.

First, demand for batteries is all about electric vehicles. Around 90% of battery demand will come from EVs over the next two decades. Growth in portable electronics and energy storage systems is modest in comparison.

On our forecasts, there are 10 million EVs on the road today, 100 million in 2030 and 400 million soon after 2040.

EVs are going to grow at a phenomenal rate: we’ve just increased our forecast to an average of 15% a year over the next 20 years. But cost disparity and the slow turnover of the car stock means it’s not until the 2030s that EVs displace ICE vehicles in big numbers. On our forecasts, there are 10 million EVs on the road today, 100 million in 2030 and 400 million soon after 2040.

Second, for EVs to go mass market is now all about battery costs. Consumer anxiety around range will be rapidly dispelled by higher energy densities and the prospect of accessible fast-charging infrastructure.

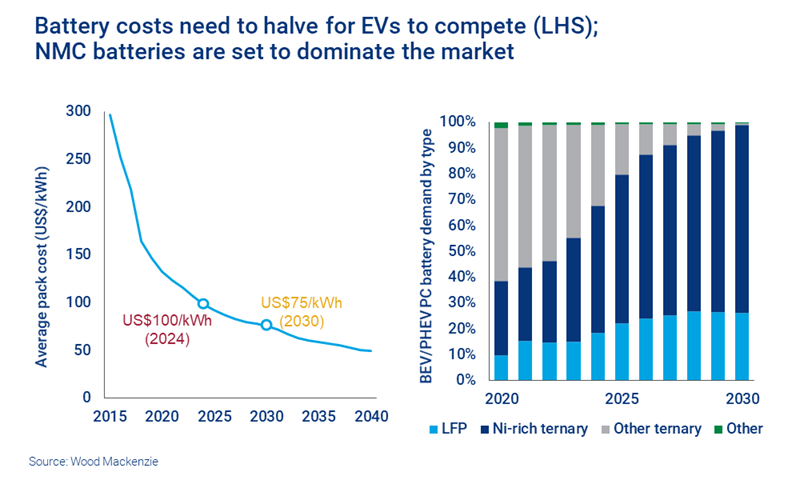

Battery costs have more than halved in five years to below US$150/kWh today and are on track, within four years, to break the US$100/kWh barrier that’s been seen as the commercial threshold. ‘Commercial’ really means fully competitive with ICE vehicles. Ultimately, consumers want parity on the price they pay for a car while automakers need the same margins and returns on EVs as they make on ICE cars.

That’s below US$75/kWh, according to the audience survey at our virtual Seoul conference last week. That won’t happen till the back end of this decade; then we’ll see more rapid growth in EVs.

Third, NMC batteries will be the dominant chemistry for the next decade at least. Most automakers are pinning strategies on these ternary batteries – lithium-ion batteries with cathodes made from oxides of nickel, manganese and cobalt – which already supply about half of EVs.

The industry has made great progress increasing energy density and reducing expensive and risky cobalt from the previous generation of cells like NMC 1:1:1. High-nickel, low-cobalt cells like NMC 8:1:1 have already been commercialised – albeit not without challenges – and are destined to capture around 60% of the EV market by 2025.

‘Older’ chemistries like lithium iron phosphate batteries (LFP), which uses zero cobalt, have enjoyed something of a renaissance in the Chinese market, due to advances in pack energy density and their inherent safety advantages. Weaker performance on range, however, suggests LFPs will still be eclipsed by NMC cells in the coming years.

Solid state batteries (SSB) are perceived as the ‘holy grail’ in the battery space, given their potential for high energy density and safety. Our view is that these ‘next gen’ batteries will only start to be commercialised beyond 2025, and even then, will initially be the preserve of higher-end applications, such as luxury and sports cars.

Fourth, supply of key battery metals needs to develop to meet the transformational demand from EVs. China’s grip on the supply chain of these metals is a concern, though there is no immediate resource supply problem to justify prices rallying today, just more of the ‘EV exuberance’ that’s got investors excited in recent months. But, further out, supply challenges loom for lithium, cobalt and nickel as EV sales ramp up. The risks around each vary considerably.

Lithium faces the steepest increase in demand, a six-fold increase from the battery sector by 2030. However, the supply base is relatively diverse, and we think under-developed, accessible low risk resources (from Australia, Argentina and Chile) can be delivered to the market to meet rising demand.

Cobalt is the red flag battery metal, the supply chain helplessly tied to the Democratic Republic of Congo with all its ESG challenges. DRC supplies over 70% of the market today and will maintain that share even as demand rises through this decade, despite new production from Australia and Indonesia.

The cobalt market falls into deficit from 2027, and once EV sales take off in the 2030s, we project mined and recycled cobalt can meet only meet half of forecast demand by the middle of the decade. The world will become ever more dependent on DRC (which can likely step up cobalt production to fill the gap) unless new battery technologies emerge to oust NMC cells.

Nickel also slips into deficit late this decade. While there’s no shortage of nickel resource, new mines (Indonesia, for example) have significant ESG challenges. Also, it can take five to ten years to deliver nickel to market from a major new project. In the aftermath of the 2020 crisis, mining companies are focused on cash flow generation and dividends rather than investing in capital-intensive new projects.

It’s not only battery and EV manufacturers anxiously watching this play out. An increasing number of governments with ambitious net-zero emissions targets also depend on the mining industry committing in time.