与我们分析师联系

Brazil's natural gas industry and that of its neighbors in the Southern Cone, such as Argentina and Chile, have labelled gas the 'fuel of the future'. The question is whether that future has finally arrived for the region, and which Wood Mackenzie explores in our latest multi-client study "Growing Pains: Identifying opportunities in an increasingly inter-dependent and dynamic Southern Cone Gas Industry".

The discoveries of the massive multi-billion barrel pre-salt oil and gas fields offshore Brazil in the last decade led many, including state-owned behemoth Petrobras, to believe that by 2015, Brazil would become a gas exporter. Today, Brazil is pumping more than 1 million barrels per day of oil equivalent of oil and gas from the pre-salt. That's good but, in a reflection of Petrobras' struggles, gone are the days when we thought Brazil would produce 5 million barrels per day.

Instead, Brazil relies heavily on imports, with half of its gas supply coming from Bolivia and three floating LNG regasification units. In 2014 and 2015, Brazil had to sign additional short-term contracts with Bolivia to supply its drought-stricken power sector. With three LNG-to-power projects, which will add 4.5 GW of generation to the grid, due to come online before 2020, LNG imports have had to pick up the slack.

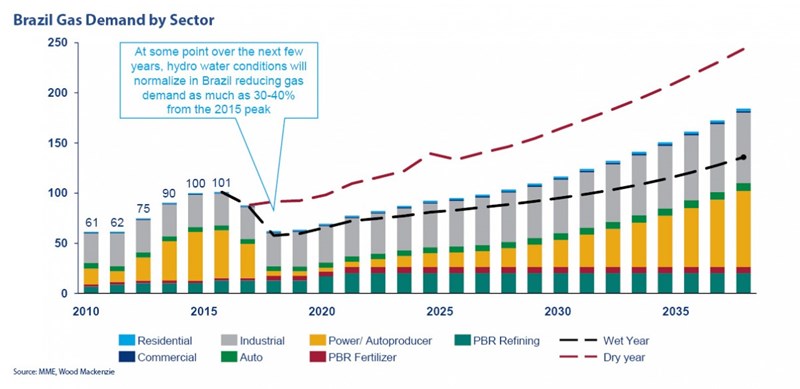

The industry today finds itself in an uncomfortable position – gas demand has grown 10% per year since 2010, with the 2012-2015 drought driving that demand growth in the power sector. This has simply masked the impact of the struggling Brazilian economy, slowing policy development, and Petrobras' project delays on long-term gas demand.

Recovering reservoir levels will boost hydroelectric generation, on which Brazil depends, and will eventually normalize power needs for gas. At the same time, more than 25GW of new hydro and renewables capacity is being built; this will complete by 2018. According to our models, in this weak market, gas demand could drop 30% to 40% in a normal hydro generation year from 2015′s record levels.

Not surprisingly, those LNG-to-power projects appear fragile at the moment, with concerns about financing, currency fluctuations, and access to long-term LNG supply. Add to that our expectation that due to Petrobras project delays, Brazil's domestic production will plateau in 2018 and Bolivia will struggle to add reserves. It would seem like a rough ride is ahead for Brazil's Gas & Power Industry. On the flip side, Petrobras' US$58 billion divestment program – the most aggressive in oil and gas industry history – could lead to unprecedented investment opportunities in the gas distribution, power, infrastructure and upstream sectors.

Argentina finds itself in a situation similar to Brazil's pre-salt 'game changer' with enormous unconventional shale oil and gas resources that the EIA pegged at 802 TCF, which is second in the world behind China's. Local politicians are suggesting Argentina will become 'self-sufficient' for natural gas and are looking to duplicate the North American unconventional oil and gas revolution.

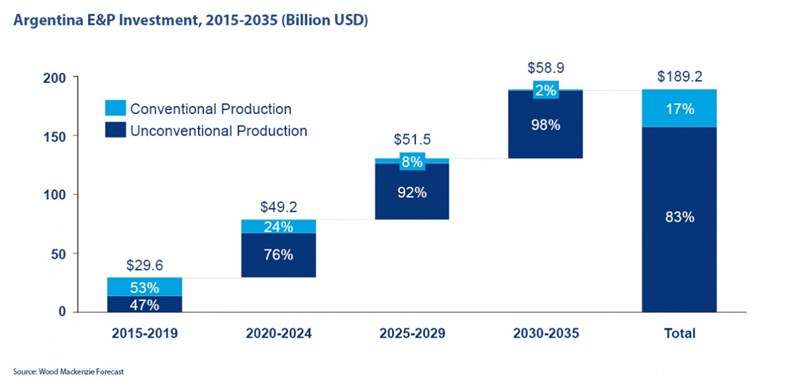

However, despite Argentina's world-class potential, there are a number of challenges. The national oil and gas company, YPF, which is responsible for most of the country's unconventional development activity today, cannot solely fund the capital required to develop Vaca Muerta shale and the Lajas and Mulichinco tight gas formations. Wood Mackenzie estimates that more than US$150 billion in capex will be required over the next two decades for unconventional development alone (83% of the total of Argentina's E&P capex). Experienced North American unconventional players might see funding a portion of this as a golden opportunity to further invest in the market as we see up to 85% of the capital coming from outside YPF.

That level of activity would require a well-functioning unconventional oil and gas supply chain – one already operating at full capacity – to drill just 200 to 300 wells a year. But our Argentina experts estimate that more than 1000 wells a year would need to be drilled from today to achieve scale. This would require not only building a strong local supply chain, but also aligning government policies with industry needs.

One good place to start is gas and power pricing policy. Natural gas and power tariffs are both heavily subsidized while the prices paid to producers at the wellhead have varied significantly. Repatriation of earnings and equipment import barriers are also key issues. Politicians across party lines are proposing potential solutions, but the industry needs to see action in 2016 from the next government.

Wood Mackenzie's projections suggest that after a short-lived increase in supply to 2017, the ensuing drop in conventional production (-12% per annum to 2035) will be hard to compensate for. Tight gas is economic, but the transition to more expensive and complex shale will be steep.

With uncertainty and volatility expected from Argentina and Brazil, flexible bi-lateral and multi-lateral commercial arrangements will be necessary to balance supply in the region. Bolivia, the swing supplier, will need to manage its key export markets (and negotiate terms) in a coordinated fashion and manage production intelligently to match domestic as well as Brazilian and Argentinian requirements. Our analysis suggests Chile is set for a power and gas capacity glut as renewables flourish and, in the next decade, this LNG importer may actually send regasified LNG across unused pipes to Argentina.

When the dust settles, what is clear is that the region's gas industry needs an annual investment influx of up to US$25 billion to US$30 billion across the value chain to keep the growth story alive.

This blog was first posted on forbes.com