Hydrogen’s critical role in the energy transition

A US$1 trillion silver bullet for hard-to-decarbonise industries?

2 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

Low-carbon hydrogen has a tiny share of the global energy market today. Investors, though, are betting on the long-term potential of this super-versatile energy carrier. Shares with meaningful exposure to hydrogen have been among the best performing in the bull run of energy transition stocks these last few months. Green hydrogen, produced by electrolysis of water using renewable electricity, is what most of the fuss is about.

Most developers and investors are still at the very early stages of working up a hydrogen strategy. I asked Ben Gallagher, our lead analyst on emerging technologies, how he sees the opportunity.

First, a dramatic policy shift in the last few months has lit the fuse. The announcement of net-zero targets from China (2060), Japan, South Korea and Canada (all 2050) and the Biden administration recommitting the US to the Paris Agreement show policy momentum to tackle global warming is now unstoppable. The world is pivoting towards decarbonisation and that’s bullish for zero-carbon technologies like green hydrogen.

The EU published its hydrogen strategy last summer aiming for 6 GW of capacity by 2024, ramping up to 40 GW by 2030. Germany, Spain, Portugal, Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, Poland and Canada all published a national hydrogen strategy in the last year. Many others will follow soon.

Second, the economic case for green hydrogen is beginning to come together. Capital costs will come down with the massive scaling up of electrolyser capacity and the associated supply chain – much as we’ve seen in other zero-carbon technologies, like solar. Electricity costs need to come down, too – the electrolysis process is very energy-intensive. Feedstock costs are 60% to 80% of the all-in costs of production, almost all of it electricity.

We reckon green hydrogen will be competitive with fossil fuel hydrogen in several markets by 2028 to 2033, assuming a US$30/MWh power price in 2030. That’s when we see the market really start to take off.

Third, there’s a gargantuan task ahead to build supply. Capacity is growing exponentially even now – the project pipeline has ballooned from just 3.5 GW a year ago to 26 GW today. Around two-thirds of that is in Europe with sizeable projects also in Saudi Arabia and Australia.

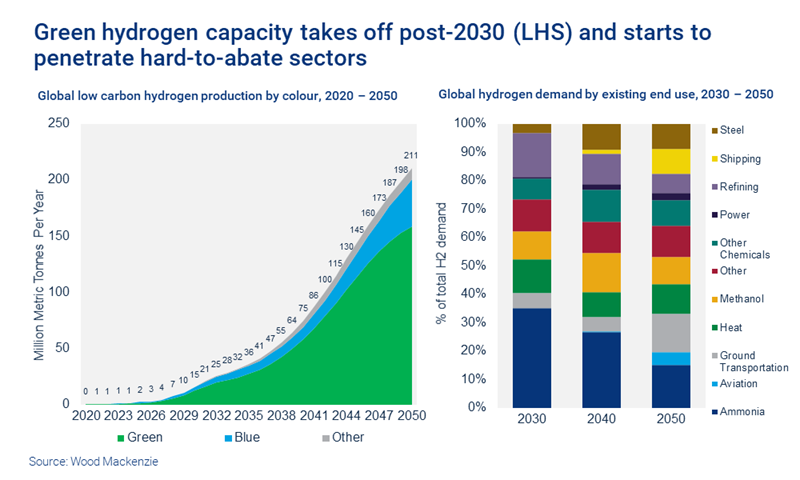

This is just the tip of the iceberg: the world is going to need almost 1000 GW of electrolyser capacity by 2050 to meet our demand forecasts. And that’s just for the green hydrogen which will be 75% of global production by 2050. CCS supporting gas- or coal-based hydrogen as well as other pre-commercialised methods of production will also need to play a significant role.

Electrolysis on that scale will absorb the equivalent of 12% of global electricity supply. That’s more than the annual supply for the entire US power market. The renewables need to be built in parallel; and it will be quite a logistical challenge to deliver reliable, cost-effective power to the electrolysers using intermittent solar or wind. Energy storage or grid-power will also have to be in the mix.

The capital cost to build out hydrogen on the production side through to 2050 will be around one trillion dollars – spend in 2020 was barely US$100 million. So far, governments collectively plan to allocate US$153 billion for hydrogen deployment and infrastructure, most likely as grants and loans in the early stages of development. They will hope to ‘crowd in’ private risk capital in the early stages of development. We think there is plenty of pent-up interest from Big Oil, utilities, energy technology specialists, venture capital, private equity, institutional investors and banks.

The biggest risk for investors is that demand disappoints.

Fourth, the biggest risk for investors is that demand disappoints. The existing market is 99% carbon-intensive, structured around use in the refining, ammonia and methanol sectors. These are the low-carbon hydrogen targets this decade, ones that already know and use hydrogen and are being pushed hard to decarbonise.

The big prize is hydrogen’s potential to decarbonise hard-to-abate sectors. But big carbon-emitters like steel, shipping, natural gas (hydrogen blending) and vehicle markets are nowhere near ready to switch. With emerging technologies, some of these opportunities could even skip hydrogen and just electrify.

Pilot projects underway in steel (due onstream 2027), gas and shipping could demonstrate proof of commerciality through the 2020s, paving the way for more widespread adoption globally over the following two decades. China and the US will be the biggest markets. In the longer term, hydrogen can disrupt the aviation, heat and power sectors.

Green hydrogen isn’t going to be an overnight sensation or the ‘new oil’ anytime soon. But we think it will play a significant role in the energy transition, meeting 7% of global final energy demand by 2050. Some, including the Hydrogen Council, think it could be a lot bigger.

Tell-tale signs will emerge this decade showing whether hydrogen is on track to fulfil its huge promise.

More insight into the issues shaping your industry

Every week in The Edge, Simon Flowers shares his take on the natural resources industry's biggest stories, how they're likely to evolve and what that means for your business. Fill in the form at the top of this page to get The Edge in your inbox.