与我们分析师联系

Fair share: why a new approach to mined energy transition resources is needed

Exploding demand for vital energy transition resources will only be met through better collaboration between all stakeholders, and the right fiscal structures

1 minute read

Graham Kellas

Senior Vice President, Global Fiscal Research

Graham Kellas

Senior Vice President, Global Fiscal Research

Over 30 years, Graham has advised on taxation matters and supported complex fiscal negotiations.

Latest articles by Graham

-

Featured

Upstream fiscal 2025 outlook

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

-

Featured

Energy fiscal policy 2024 outlook

-

Featured

Conflicting ambitions will shape the upstream fiscal landscape in 2023 | 2023 outlook

-

Opinion

Fair share: why a new approach to mined energy transition resources is needed

-

Featured

Stage set for tougher fiscal terms for upstream operators in 2022 | 2022 outlook

Many key energy transition resources are in high demand but short supply. This imbalance means a lot more investment is needed to support an energy transition at the pace required. And for that to happen successfully, mining companies, investors, governments and other stakeholders will all need to embrace a far more collaborative working relationship.

In our report Transition resource rents: establishing a fair share, we explore how the financial and fiscal arrangements around mined commodities can and must be made fairer. Visit our store to download the full report. Or read on for a short introduction.

Energy transition metals: what’s the problem?

Achieving an energy transition pathway consistent with Paris and COP26 objectives will require massive investment in everything from electric vehicles and wind turbines to solar panels and hydrogen production units. That in turn will create soaring demand for commodities including lithium, graphite, cobalt, nickel, copper and aluminium.

However, obtaining adequate supplies of these vital transition resources will be severely hampered unless the mining business environment becomes more conducive to higher levels of investment. And the history of mining operations is characterised by adversarial relationships that often delay and disrupt operations.

Who’s involved?

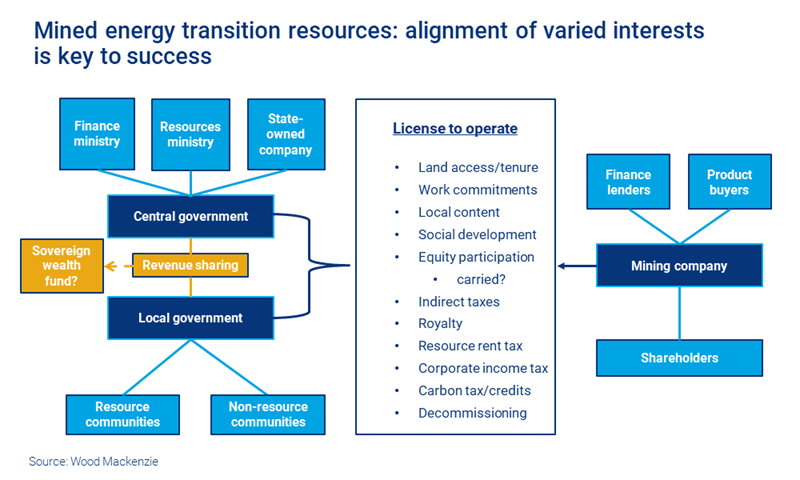

While the key relationships are between mining companies and the governments of host countries, shareholders, financiers, and product buyers have an important role to play.

-

Mining companies

Miners themselves are increasingly aware of their obligations to wider society; in an EY survey, mining companies ranked environmental and social issues as the number one risk for the sector.

-

Host countries

The number of countries hosting relevant mining operations is set to grow significantly. Many of these have not contributed to the global warming problem but are critical to the solution. For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo for cobalt, copper and lithium, Guinea for bauxite (for aluminium), Mozambique and Madagascar for graphite, and the Philippines and New Caledonia for nickel.

-

Shareholders, product buyers and financiers

Those providing the money for mining development are increasingly demanding high environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings when allocating capital. But they must accept that means resource rents need to be shared more evenly and are not simply the rewards for providing capital.

-

Renewable energy companies

Some firms reliant on transition resources are making bold moves to secure critical supplies – for example, Tesla’s agreement to buy the entire supply of the Goro nickel operation in New Caledonia.

Why stronger relationships are vital in delivering vital mined energy transition resources

Mining development is costly, risky and time-consuming. Tense and lengthy negotiations and renegotiations between extractive resource owners and investors over fiscal terms, local content and social development issues are common and impede development.

For the world to get enough of the transition resources it badly needs within the short timeframe required, host countries need to maximise interest in resource opportunities by presenting the best business environment possible to prospective investors.

What needs to change to establish a fair approach to developing transition resources?

Host countries need to acknowledge that competition for scarce capital is fierce. To secure investment, finance and resource ministries, state-owned mining companies, sovereign wealth funds and local communities all need to be aligned behind clear, consistent, predictable policies that can adapt to a rapidly changing economic environment.

Price windfalls and crashes usually lead to heated debates both between host governments and investors, and between central and local governments. Agreed internal revenue-sharing mechanisms and a flexible, synchronised fiscal policy that ensures all stakeholders receive a share fair of revenue through price cycles are therefore vital.

What does an effective relationship look like?

To create a working relationship that benefits all stakeholders, transparency and flexibility are essential. Initiatives are underway to publish all new mining agreements – that will engender greater trust between parties and give long-term projects the greatest chance of success. At the same time, mining companies should reconsider policies and practices designed to minimise costs and taxes as part of their ESG policies.

Meanwhile, on the fiscal side, policies must reflect a host country’s economic circumstances. For example, demands for upfront money may deter investors, but can countries afford to wait until all costs are recovered before receiving a revenue share? Terms need to be able to automatically respond to factors including the size and quality of resource deposits, extraction and delivery costs, and volatile commodity prices.

Other points to consider include:

-

Indirect taxes should be minimised

Until revenue is generated, the host country should focus on the benefits of employment and growing the local supply sector.

-

Royalties should give way to profits-based taxes

Royalties can help in the early stage of sector-building, but should be phased out in favour of profits-based taxes as the sector matures.

-

Any depreciation should be balanced by low tax rates

In immature sectors depreciation may be necessary at first, but it should be balanced by low tax rates.

-

Beneficiary countries could finance host country participation

Rich, high carbon-emitting countries could help ensure success by financing a host government’s equity position in new projects as part of the just transition envisaged by the Paris Agreement.

Ultimately, success relies on governments and investors agreeing clear, predictable, stable, progressive terms and then sticking to them. Having participated in fiscal discussions between resource producers and governments for many decades, we know this vision may be considered overly optimistic. But if the world is to have any hope of achieving COP26 goals, some energy transition fantasies must become reality.

Want to learn more?

Visit our store to access the full report, which draws on insight from our Fiscal Service and Metals & Mining team to provide in-depth analysis of different fiscal approaches to transition resource rents.