Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

Where net zero ambitions, oil and gas production and domestic politics clash

3 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

Graham Kellas

Senior Vice President, Global Fiscal Research

Graham Kellas

Senior Vice President, Global Fiscal Research

Over 30 years, Graham has advised on taxation matters and supported complex fiscal negotiations.

Latest articles by Graham

-

Featured

Upstream fiscal 2025 outlook

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

-

Featured

Energy fiscal policy 2024 outlook

-

Featured

Conflicting ambitions will shape the upstream fiscal landscape in 2023 | 2023 outlook

-

Opinion

Fair share: why a new approach to mined energy transition resources is needed

-

Featured

Stage set for tougher fiscal terms for upstream operators in 2022 | 2022 outlook

Gail Anderson

Research Director, North Sea Upstream

Gail Anderson

Research Director, North Sea Upstream

Gail focuses on the North Sea Upstream industry and its gas and power sector.

Latest articles by Gail

-

Opinion

North Sea upstream: 5 things to look for in 2025

-

Opinion

Video | Shell and Equinor announce UK asset merger to create new JV

-

Opinion

End of an era looms as Chevron seeks UK exit

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

-

Opinion

North Sea upstream: 5 things to look for in 2024

-

Opinion

The challenges and opportunities in Europe’s oil & gas, CCUS and hydrogen sectors

James Reid

Senior Research Analyst, North Sea Upstream

James Reid

Senior Research Analyst, North Sea Upstream

James focuses on North Sea Upstream

Latest articles by James

-

Opinion

End of an era looms as Chevron seeks UK exit

-

Opinion

NEO Energy and Sval Energi sale rumours - what could the portfolios offer a buyer?

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

How can a government simultaneously manage its declining upstream sector, build a low-carbon energy system and balance the Treasury’s books? It’s a transition challenge many oil-producing governments face. Graham Kellas, Gail Anderson and James Reid, of our North Sea and fiscal teams, assess the UK’s moving fiscal feast and argue for a smart tax system that might show the way for other oil-producing countries.

First, the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) is an ultra-mature oil and gas province. Almost 90% of the 48 billion barrels of commercially recoverable oil and gas resource (boe) has already been produced. Of the 6 billion boe remaining, 3.6 billion boe are held in fields already in production or under development and 2.3 billion boe are pre-FID projects. All these barrels require investment, and most depend heavily on utilising the UK’s extensive existing offshore infrastructure.

Second, the UK’s upstream industry sector has rapidly become a political football. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine drove oil and gas prices through the roof, suddenly resurgent North Sea cash flows proved too tempting for a Conservative government desperate to find additional tax revenue.

The Energy Profits Levy (EPL), initially introduced in May 2022, almost doubled the effective marginal tax rate from 40% to 75% through 2029. It’s a quirky tax, with ‘floors’ for oil and gas prices that have yet to be triggered, despite prices falling substantially since 2022. It’s also created winners and losers – capital and investment allowances heavily favour companies with taxable income and projects to invest in.

The opposition Labour Party, widely expected to win the election due later in 2024, intends to introduce a “proper” windfall tax. Labour plans to raise the tax rate to 78% and hints at ending loopholes that “funnel billions back to oil and gas giants”. Ending capital and investment allowances could lift the effective tax rate for some companies to over 100% of pre-tax cash flow. A 78% tax rate would match neighbouring Norway’s – but unlike the UK, Norway still has prolific resources to be developed and also offers significant capital allowances.

The EPL hit to cash flows and the economic value of UK Upstream Inc. is already material. Prior to the EPL, the pre-tax NPV of all UKCS assets was split 67/33 in favour of UK North Sea producers whose share was £58 billion. The EPL has shifted the current ratio to 40/60, and reduced producers’ share to £37 billion. Under Labour’s plans the ratio moves to 30/70, and producers’ share falls to £26 billion on our calculations.

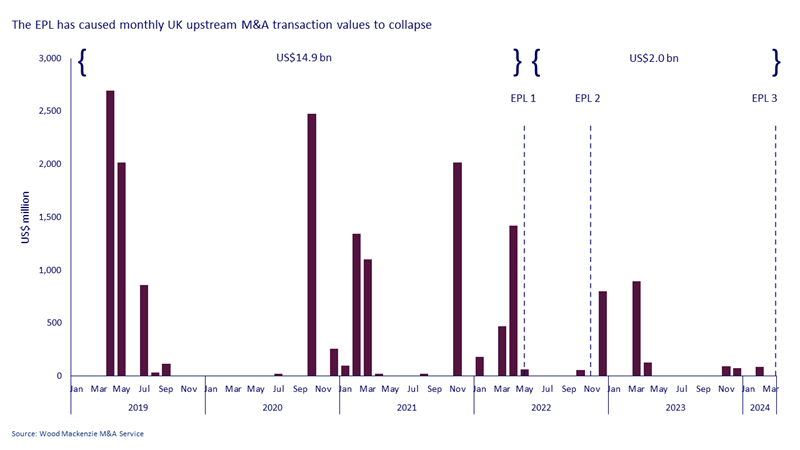

Third, uncertainty kills investment. It’s already stifled the flow of capital into the UK North Sea. The value of transactions has dried up since May 2022, barring an EPL-inspired exit (Suncor) and defensive consolidation (Serica/Tailwind and Ithaca/Eni). Since the introduction of the EPL, buyers have little appetite to expand or enter the UKCS.

With upstream players dedicated to tight capital discipline, organic investment is also under threat. We estimate that £16 billion spend on brownfield and greenfield projects could be lost to the sector, over half the total expected future UK upstream spend of £28 billion. A domino effect would follow – contraction of the service sector, job losses, redundant oil and gas infrastructure that limits development plans for offshore wind and CCUS, and the early decommissioning of fields with the inevitable related costs to the government.

As the UK government seeks to draw in huge capital for green investment, tinkering around the EPL risks sending the wrong message. The big investors the UK will rely on to scale up the green energy system will want fiscal stability but may wonder if they’re next.

Finally, there’s a growing understanding of interdependencies between the declining and emerging energy sectors. UK producers, the service sector and North Sea infrastructure together have an important part to play in the buildout of low-carbon industries, including offshore wind, hydrogen and CCUS. Upstream investment and cash flows can support the industry’s own decarbonisation strategies while the tax revenue can likewise support the government’s general budget plans, including its net zero targets.

What’s needed is a fiscal policy to reflect those interdependencies – to incentivise investment across upstream, the low-carbon technologies and infrastructure of the future, and the transfer of jobs and skills to new industries. Grasping the opportunity would provide a smart fiscal template other mature oil- and gas-producing countries can use in their own transition.

Make sure you get The Edge

Every week in The Edge, Simon Flowers curates unique insight into the hottest topics in the energy and natural resources world.