Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Is consolidation changing upstream’s appetite for investment?

Capital discipline is still central to corporate strategy

4 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

Fraser McKay

Head of Upstream Analysis

Fraser McKay

Head of Upstream Analysis

As head of upstream research, Fraser maximises the quality and impact of our analysis of key global upstream themes.

Latest articles by Fraser

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: diverging development strategies in Latin America, investment at risk in Africa, and Kazakhstan supply tensions explained

-

Opinion

Is oil price volatility a threat to upstream production, investment and supply chains?

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: UK fiscal changes and an Asia-Pacific licence bonanza

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: the global sanctions slump, grappling with gas and potential US tailwinds

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: the global sanctions slump, grappling with gas and potential US tailwinds

-

The Edge

Why upstream companies might break their capital discipline rules

Leslie Cook

Principal Analyst, Upstream Supply Chain

Leslie Cook

Principal Analyst, Upstream Supply Chain

Leslie is a principal analyst and project manager for Wood Mackenzie's portfolio of drilling and rig products.

Latest articles by Leslie

-

The Edge

Is consolidation changing upstream’s appetite for investment?

-

Opinion

Headwinds to tailwinds: are deepwater rig companies ready for a modernised upstream industry?

-

The Edge

Does the bull market in oil rigs signal a slower transition?

Andrew Thorburn

Global Head of Cost Analysis

Andrew Thorburn

Global Head of Cost Analysis

Andrew is responsible for upstream supply chain and cost analysis.

Latest articles by Andrew

-

Opinion

Video | Tariff turmoil: how big a cost hit will US oil and gas operators take?

-

The Edge

Is consolidation changing upstream’s appetite for investment?

There are lots of drivers of the current intense phase of upstream corporate takeovers including scale, low costs and resilience. A big one, though, is buyers’ rising confidence in the durability of oil and gas demand. So, what does it all mean for the organic investment required to deliver the new supply to meet demand? I asked our team for their thoughts.

First, sustained investment in oil and gas supply will be needed for decades to come. Peak oil demand doesn’t happen until 2030 in our Energy Transition Outlook (ETO), before declining gradually; peak gas demand follows a decade later. In an electrifying world, almost two-thirds of the US$52 trillion of investment in energy supply through 2050 will be power and renewables. Upstream spend will still be significant at US$14 billion in our ETO, and US$7 trillion in our Net Zero Scenario.

Second, the present investment rate is delivering sufficient new supply to meet the growth in oil and gas demand. Upstream spend on development and production has bounced back by 30% in real terms from the pandemic-induced low of 2020 to just below US$500 billion in 2024. That’s still just half the 2014 peak, a level that’s prompted others to suggest that the industry is under-investing and heading for a supply crunch.

We have never bought into this view. Our analysis shows that upstream has been able to deliver an average of 2.5 million boe/d of new oil and gas supply over the last several years, ample to meet demand growth. An improvement in capital efficiency by around two-thirds, and strict operator discipline have worked wonders. Saudi Aramco’s recent decision not to add another 1 million b/d and raise its oil production capacity to 13 million b/d by 2030 corroborates our supply view and underlines the industry’s commitment to capital discipline.

Third, where upstream spends its money is shifting as IOCs and NOCs increasingly focus on delivering advantaged barrels – low cost, low carbon intensive supply. The big winner has been deepwater, a segment that has unearthed most of the giant oil and gas discoveries of the last decade, in basins such as Brazil, Guyana, Suriname and Namibia. Deepwater’s share of investment will double through the middle of the decade compared with 2020, as will the share of global oil and gas production.

Investment in conventional projects, offshore and onshore, continues to dominate spend with over 40% of the total, but the share is in gradual decline. Investment in tight oil and unconventional gas is set to remain fairly stable at around one-third of the global total, irrespective of the sector consolidation underway.

Fourth, there are still constraints on investment. Capital availability isn’t so much the issue for companies that don’t need external finance - cash generation is near all-time highs. Capital discipline, though, is central to every company’s strategy, with the focus on maximising free cash flow and returns to shareholders rather than investment in growth.

Supply chain capacity varies across segments and regions. In some sectors, there is still flexibility. Having come through a period of near-capacity activity, the US Lower 48 has a little slack in the system enabling operators to add more rigs and completion crews. But it’s the US upstream that’s most under the microscope to demonstrate capital discipline. While we think consolidation may herald a new phase of tight oil growth, this time it will be more rational, more ‘big corporate.’

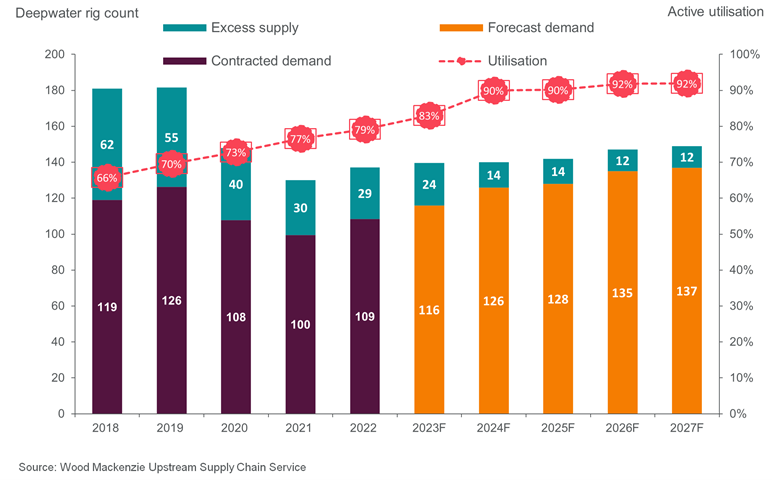

The Deepwater supply chain, in contrast, is already severely stretched. The most advantaged and capable deepwater rigs are already effectively ‘sold out.’ Our supply chain analysis suggests the sector only needs to add seven more rigs (a combination of niche newbuilds and reactivations) to meet our projected demand.

Rig-rates have doubled over the last five years to an average of over US$400,000/day, and TotalEnergies’ acquisition of a 75% stake in a drillship indicates the growing pressure on operators to secure rigs without overpaying or committing to long-term contracts at high prices.

Operators still have some wiggle room to offset rising rig costs with efficiencies. But if deepwater rig demand continues to grow newbuilds won’t come cheap. We reckon to pay its way the rate for a new build 8th generation rig would have to nearly double again to an all-time high of US$700,000/day.

We doubt it’s a record operators will be willing to set. Indeed, this phase of consolidation isn’t just about doubling down on oil and gas and meeting growing demand. Buyers, and the wider industry, will be at pains to demonstrate that the industry is still remorselessly focused on all the elements that have helped rejuvenate the sector in the eyes of investors – building resilience, keeping costs low, and holding the line on capital discipline.

Make sure you get The Edge

Every week in The Edge, Simon Flowers curates unique insight into the hottest topics in the energy and natural resources world.