Find out how our Consulting team can help you and your organisation

Evaluating infrastructure and optionality in Canadian hydrocarbon exports

A world of opportunities?

12 minute read

Kian Akhavan

Consultant, EMEA

Kian Akhavan

Consultant, EMEA

Kian is a specialist in public policy, with a focus on public-private partnerships.

Latest articles by Kian

-

Opinion

Reassessing Canadian Export Infrastructure

-

Opinion

Evaluating infrastructure and optionality in Canadian hydrocarbon exports

-

Opinion

How public-private partnerships can accelerate the energy transition

The relationship between Canada and the United States has frayed in recent months as Washington has threatened to impose crippling tariffs on Canadian imports and to annex the country altogether. During Canada’s recent federal election campaign, newly elected Prime Minister Mark Carney offered a damning assessment on the state of the country’s relationship with the United States:

"The global economy is fundamentally different today than it was yesterday. Our old relationship with the United States is over. While this is a tragedy, it is also the new reality. Canada must be looking elsewhere to expand our trade, to build our economy and to protect our sovereignty. And if the United States no longer wants to lead, Canada will."

A big part of the re-evaluation of this relationship will take place in oil and gas markets. In 2023, the US accounted for 96% of Canada’s total hydrocarbon exports – over 20% of the country’s total goods exports.

Carney has promised to make Canada an “energy superpower” by investing in renewable and fossil fuel infrastructure and diversifying trade away from the United States. This would mark an unprecedented shift in Canadian economic and energy policy, giving producers greater reach and helping to maximise the value of their products. However, Canada’s access to non-US markets is severely constrained due to insufficient infrastructure.

As the new government’s mandate begins, it will need to contend with several key questions. Can Canada move away from its longstanding role as a regional energy supplier to become a global superpower? Is it ready to be? How soon? The outlook is potentially very promising, but to reach this ambition the country will need to invest heavily in its hydrocarbon infrastructure.

Tariffs, optionality, and the status quo

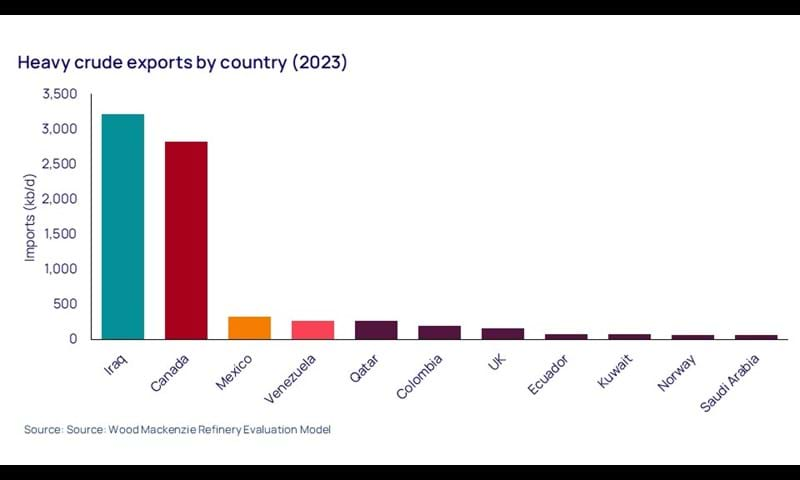

Canadian hydrocarbon exporters are massively reliant on the United States, with 97% of crude oil and 100% of natural gas exports sold to the American market in 2023 (the most recent year for which official data is available). This reliance is generally asymmetrical; many American refineries can import comparable heavy sour crude from other countries at a discount to Canadian crude at risk of heavy tariffs, and the US is the world’s largest gas producer.

Flexibility among American refiners is not uniform. Assets in Texas or Louisiana can benefit from their coastlines to replace Canadian crude with volumes from other producers of similar quality oil, though this is not without its challenges. For example, US sanctions on Venezuela are highly unlikely to be lifted, barring a significant shift in American foreign policy. This precludes Venezuelan heavy crude as a supplement for potentially tariffed barrels in the US crude slate.

Wood Mackenzie does not anticipate a significant increase in crude shipments from Mexico, as uncertain tariff schedules and the startup of Pemex’s Dos Bocas refinery are likely to increase Mexico’s domestic crude consumption, cutting exports to the US Gulf Coast.

The impact of this dynamic on Canadian oil exports is complex and depends on several moving parts. Imports of CUSMA-compliant goods are temporarily exempt from US tariffs, but the situation remains turbulent, both in terms of trade barriers but also of retaliatory measures. When the first tranche of tariffs was announced, Canadian energy imports were taxed at 10% while Mexican imports were taxed at 25%. If Mexican oil is once again disproportionately tariffed compared to Canadian oil, this might lead to greater demand for Canadian barrels at Gulf refineries. However, this may be partially offset by the recent shutdown of Lyondell Houston refinery, which was optimised to run heavy crudes.

This leaves Iraq as the best alternative for importing heavy crude. Iraqi barrels have greater global reach, with regular shipments to international markets including China and India. Basrah Heavy is generally slightly lighter than WCS Blend but has a similar sulphur content, making it an easy replacement for refineries; the US imported over 200 kb/d of heavy Iraqi crude in 2023.

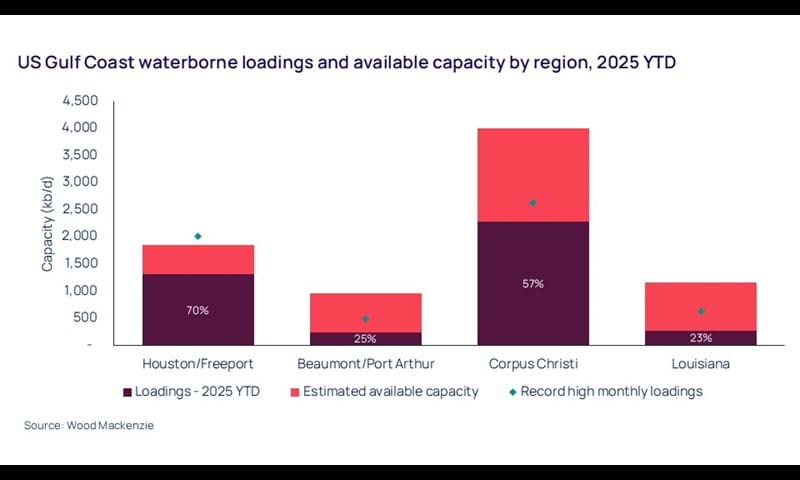

West Coast refineries, while also benefitting from access to shipped volumes, are more limited in their choices. The TMX pipeline, running through Alberta and British Columbia to the Port of Vancouver, has boosted optionality for shipping Canadian barrels to other Pacific basin markets, and higher tariffs are likely to gradually shift exported volumes to Asia.

Landlocked Midwestern refineries are the most reliant on Canadian imports, lacking viable alternatives. Pipeline routes that used to flow north to provide access to seaborne crude were all reversed over the past two decades as Canadian oil sands volumes grew rapidly. Therefore, these refineries will remain reliant on Canadian crude even under high tariffs, but they may benefit from a WCS benchmark that is discounted to remain competitive under tariffs. These refineries are likely to have tighter margins than coastal refineries but will continue to purchase Canadian oil.

The story is similar for gas. Wood Mackenzie anticipates an influx of Northeast American gas into Eastern Canada as local demand grows. Its relative share is likely to shrink as AECO margins decrease to regain some market share in both countries. The major difference here is that the United States, as the world’s largest gas producer, could theoretically replace imported gas with domestic volumes if Canadian producers are priced out of its market with higher tariffs.

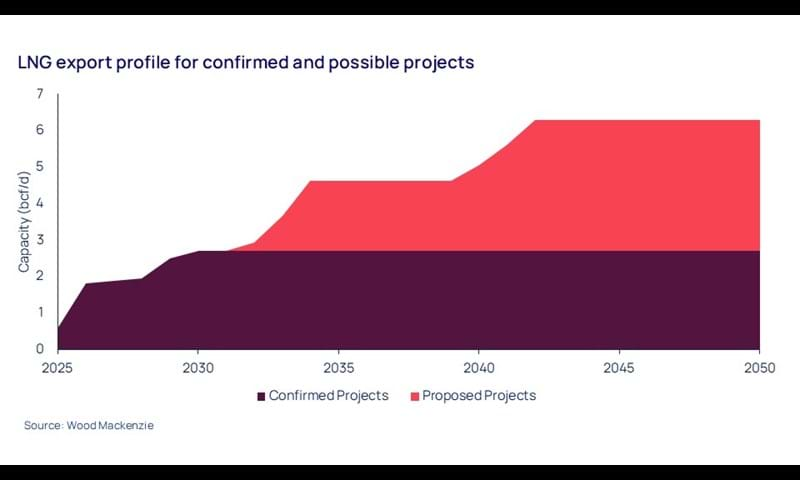

The biggest near-term upside for Canadian gas exports is the startup of LNG Canada Phase I, which is scheduled to come online later this year. Several additional LNG projects are set to begin operations across British Columbia in the coming years, quickly adding export capacity and both flexibility and access to new markets. Until then, all Canadian gas exports will continue to be sold to, or exported through, the United States. Nevertheless, demand for Canadian gas is expected to grow both domestically and internationally.

In the current state of play, Canadian oil and gas exports to the United States are likely to remain largely unchanged. LNG Canada will divert some flows to new markets, but the bulk of exported Canadian gas volumes will continue to flow south. The reimposition of a 10% tariff would hurt Canadian producers’ margins more than that of American buyers, but it’s survivable for both players. In such a scenario, Canadian prices would adjust to remain predominantly in American markets, in part due to a lack of access to alternatives. A tariff of 25% or more would completely reshape the trade landscape, forcing both buyers and sellers to look elsewhere and putting a significant dent in everyone’s margins.

Infrastructure and Export Capacity

Canada and the United States share the longest undefended border in the world. This has generally been a major economic advantage for both countries, doing wonders for Canada’s economic development while the United States’ own growth has effectively been subsidised by cheap and plentiful Canadian natural resources.

This beneficial status quo has left the Canadian export economy largely dependent on its southern neighbour – most commercial exports from Canada are sent to or through the United States. This is not entirely surprising: the relationship has been stable and mutually beneficial for most of both countries’ histories, and a peaceful land border with the largest economy in history is typically an enormous benefit to any country. However, in energy as in most industries, this has also led to complacency in developing infrastructure to diversify Canada’s export partners.

Trans-shipment through the United States is a workable arrangement for Canadian producers; American export infrastructure is well-developed and has sufficient surplus capacity for Canadian products. While this status quo may not be politically popular, these flows are likely to stay stable regardless of tariff scenarios because trans-shipped goods are exempt from potential tariffs, and the largest percentage of these volumes re-enter Eastern Canada for domestic consumption.

The development of Canadian energy export infrastructure suffers from domestic opposition as much as it does from the complacency that comes with geographical convenience. In Eastern Canada particularly, provincial governments have consistently opposed pipelines on the grounds that they would not meet provincial environmental regulations. This has been a divisive issue in Canadian civil society, with public opinion varying by province. While the debate over environmental concerns is urgent and extremely important, it has historically overshadowed the conversation of export optionality in Canada. However, while environmental concerns are still top of mind for many Canadians, developing new energy infrastructure has also increased in importance, particularly for provincial politicians.

The development of an energy corridor between Alberta and Eastern Canada has been discussed for several decades but has only been partly developed, in large part due to opposition from the governments of Ontario and Quebec. The TC Energy Canadian Mainline gas pipeline stretches from the Eastern border of Alberta to the outskirts of Montreal (via Toronto) and is the main source of domestic gas transport. There are discussions of increasing the pipeline’s capacity to meet growing demand in Eastern Canada or convert one of its lines to carry oil, though there is notable opposition from provincial governments, particularly in Quebec. The closest equivalent for transporting oil is the Enbridge Mainline system, which ends in Southern Ontario but connects to smaller pipelines that continue up to Montreal. More of this pipeline runs through the United States than Canada, and most of the shipped volumes are consumed south of the border.

Feelings towards developing a more extensive national pipeline network have been changing recently. In March 2025, the government of Quebec stated that it would support the construction of a cross-country pipeline network, provided that it was “socially acceptable” – a tepid but unprecedented show of support for a project it has historically opposed.

This newfound support is broadly reflected among ordinary Canadians as well; a poll taken in early April showed that 58% of Canadians support an East-West pipeline for both oil and natural gas, while an additional 15% somewhat support the project. This marks a clear change of priorities among Canadian voters and, as a result, for both provincial and federal lawmakers. While this risks negatively impacting Canada’s energy transition targets, it could theoretically offer valuable optionality for Canadian exporters who may struggle to sell to the American market because of growing and unpredictable trade barriers; an East-West pipeline network would increase the possibility for domestic use of Canadian natural resources and the potential to export goods to Europe. Despite these shifting tides, strong opposition to these projects remains, particularly on social and environmental grounds at the provincial and federal levels, particularly in Quebec, as well as among Indigenous governments and civil society groups.

Ultimately, a national energy corridor is more likely to serve an energy security function than to meaningfully increase Canada’s oil and gas exports to Atlantic markets. For example, most volumes from a TC Pipeline extension in Eastern Canada will serve growing domestic demand rather than creating new export markets. With high development costs, provincial fracking bans, no local production and political opposition from Quebec, major export infrastructure projects face seemingly insurmountable hurdles in Eastern Canada.

Likewise, there is unlikely to be sustained demand for Albertan oil in Eastern Atlantic refineries; European refineries are generally configured to process lighter, sweeter crudes, and West African refineries rely more on domestic or regional volumes. Furthermore, the downstream sector is shrinking across OECD countries, with liquids demand expected to peak sometime in the next decade. Demand for hydrocarbons is expected to grow rapidly in West Africa, but most of this supply will not be met with transatlantic imports.

The outlook for LNG exports is very promising, with terminals being built up the coast of British Columbia to meet rapidly growing international demand. Canada’s Pacific coast is closer to producers and benefits from the shortest distance between North America and Northeast Asia. To this end, Phase I of LNG Canada is expected to begin operation later in 2025, with Woodfibre LNG expected to start in 2027 and Cedar LNG in 2028. There are ongoing discussions for developing additional LNG projects in British Columbia, including a second phase of LNG Canada, expanding Tilbury LNG and building Ksi Lisims LNG.

Government Support

The new government faces many significant challenges if it wants to expand and diversify Canadian natural resource exports in the short term. If a major new infrastructure project is to begin construction in the next four years, both provincial and federal governments will have to become directly involved to accelerate approval processes and encourage investment in high-risk, capital-intensive projects.

The federal government is likely to provide significant financial and regulatory support for new energy projects. It will be interesting to see how it reconciles its stated development goals with the Impact Assessment Act, part of the controversial Bill C-69, which has been characterised by its critics as a major hurdle to developing major infrastructure projects, particularly for fossil fuels. Nevertheless, it has committed to amending the most stringent parts of the bill to significantly reduce approval times for new projects.

Federal and provincial governments will have to make a concerted effort to incentivise investments in major, often risky infrastructure projects. Namely, these projects can take several years to reach FID, and even longer to be built and to become operational. Even under Wood Mackenzie’s delayed transition scenario, the world will continue to decarbonise and demand for hydrocarbons, particularly in Canada’s main export markets, will continue to decrease, likely peaking before 2040, with demand for oil falling faster than demand for gas. This is, of course, a major consideration in assessing the economic viability of any major investment in dedicated export infrastructure.

To reach its ambition of becoming an energy superpower, Canada needs to invest significantly in its hydrocarbon infrastructure. The outlook for LNG is overwhelmingly positive. Canada is a Pacific nation as much as it is an Atlantic one, and it is uniquely positioned to deliver large volumes of a vital transition fuel to growing markets with several high-capacity projects being discussed or developed across the Pacific Coast. While they have not been discussed in this piece, discussions around Arctic export ambitions have been reinvigorated in recent months as part of the broad effort to reduce Canadian reliance on the American market.

The overall approach to developing new export infrastructure will be guided by the federal government’s approach to decoupling the Canadian economy from the United States. If Ottawa assesses that this relationship has truly and permanently ruptured, then it will have a starting point from which to implement policy changes to reposition the country’s hydrocarbon exports. However, the calculus is different if they deem the current tensions to just be a blip in an otherwise mutually beneficial and stable alliance. Regardless of the state of Canada-US relations, the federal government has committed to connecting provincial economies more closely and is very likely to invest in infrastructure to facilitate that goal.

The government will then need to navigate the challenges of legislating without a parliamentary majority, as well as economic uncertainty, the growing risk of a global recession, increasing geopolitical tensions, oppositional provincial governments, environmental concerns, winning the support of Indigenous communities, constraints on public finances and a private sector wary of high-risk Canadian infrastructure projects. These problems are real, but they are not insurmountable. Thoughtful and creative approaches from both the public and private sectors can mitigate much of this risk and reach desired outcomes in whatever way is needed.

If you would like to learn more about this research, fill in the form above to discover how our Consulting team can support your organisation.