Can chemical recycling make plastic more sustainable?

New technologies offer huge potential to increase recycling rates – but there are critics

1 minute read

Guy Bailey

Head of Oils & Chemicals Markets

Guy Bailey

Head of Oils & Chemicals Markets

Guy brings over 15 years of experience in regulation and sustainability.

Latest articles by Guy

-

Opinion

Can legislation unlock a circular plastics economy?

-

Opinion

COP26: Can petrochemicals square the circle?

-

Opinion

Can chemical recycling make plastic more sustainable?

-

Opinion

Can bioplastics make the chemicals industry greener?

-

Opinion

What can the materials transition learn from the energy transition?

-

Case Study

Making materially better choices

Chemical recycling is attracting serious interest and investment. Still in its relative infancy, the technology carries a weight of expectation as a possible solution to the mountain of plastic waste created every year. But not everyone is convinced – chemical recycling is not without its critics and there will be challenges to overcome if it’s to live up to its hype.

In the second part of our Chemical Solutions series, we explore the potential of these nascent technologies. Fill in the form for the insight brochure, which includes sample charts and an overview of the rest of the series. Or read on for an introduction to the pros and cons of chemical recycling.

Bringing plastic waste full circle

Around 220 Mt of plastic waste is generated each year. Of this, around 90 Mt is mismanaged (leaking into the natural environment), 70 Mt is landfilled, 30 Mt is incinerated, and another 30 Mt is recycled. Creating a genuinely circular economy – and advancing the materials transition – depends on finding ways to recapture more value from the waste stream and boosting recycling rates.

Chemical recycling currently accounts for less than 1% of this recapturing process. But judging by activity from refiners through to consumer-facing brands – in the form of pilots, partnerships and investment – there is real scope for rapid expansion.

Chemical recycling versus mechanical recycling

There are multiple competing approaches to chemical recycling. Plastic-to-plastic (P2P) recycling turns waste directly back into feedstock that can be reconverted to plastic applications. Plastic-to-feedstock (P2F) technologies create a longer loop, converting the waste stream into hydrocarbon products. These can be processed and provide feedstock at the top of the petrochemical value chain, or be used for other energy applications.

Chemical recycling has many advantages over mechanical recycling, the current dominant process. The mechanical approach is more costly, requiring a flow of high-quality feedstock. Any additives or pollutants, such as colouring, can lead to reduced-quality material or lower volumes.

Key differences between mechanical and chemical recycling

Getting value out of harder-to-recycle plastic

One of the main driving forces for chemical recycling is its potential to unlock value in waste previously regarded as difficult to recycle.

HDPE and PP bottles and rigid packs, for example, are typically coloured, which lowers the value of the recyclate. Chemical recycling removes the colouring which makes this highly recyclable material much more valuable.

Mixed-waste bales also move further up the value chain. P2F processes don’t require the same stringent levels of sorting as mechanical recycling – often the costliest element of the process.

How will moving waste further up the value chain help tackle the 90 million tonnes of plastic leaked into the natural environment each year? Find out more in the full report – fill in the form for a preview.

Expanding the potential of lightweight flexible packaging

There’s been a big push for brands to ‘downgauge’ packaging – a combination of consumer pressure over plastic and a desire to cut packaging costs. Flexible packaging and films perform well in this regard, but aren’t recycled in large volumes for technical, collection and economic reasons. In the US, for example, about 30% of PET and HDPE bottles are recycled each year, compared to less than 10% of bags and wraps.

Chemical recycling will significantly boost the reprocessing rate of these flexible applications, making them more attractive for brands with recycling commitments.

Chemical recycling could reduce fossil fuel extraction and CO2 emissions

Chemical recycling is energy-intensive. But if incinerated and landfilled waste can be moved to disposal via chemical recycling, the industry could reduce its overall emissions intensity and displace virgin feedstocks.

This displacement would mean more hydrocarbons could be left in the ground. P2P technologies displace the need for petrochemical feedstocks altogether, while P2F technologies produce feedstocks that can be reprocessed in refineries, in place of oil and gas products.

Read the full report for comparisons of CO2 emissions of mixed plastic waste and new product production.

But is chemical recycling really a sustainable choice?

Chemical recycling is not universally hailed as the solution to the challenges facing the plastics value chain. A recent report by GAIA made objections on environmental grounds, while Greenpeace has questioned whether the approach is likely to succeed in increasing recovery of post-use plastic waste.

Concerns vary by technology type, but three key themes have emerged:

- Chemical recycling generates high carbon emissions. Plastic that can be mechanically recycled will emit more CO2 if it is processed via energy-intensive chemical recycling.

- Chemical recycling leaves toxic by-products. Toxic substances produced in the chemical recycling process, such as cadmium and mercury, are costly to dispose of and could leak into the environment.

- Chemical recycling could be a form of ‘wishcycling’ or greenwashing. Critics fear that the industry could become complacent, assuming the technology will inevitably scale. With such limited operational capacity today, many bold assumptions made about future growth are inherently uncertain.

So, can chemical recycling improve the sustainability of the plastics value chain?

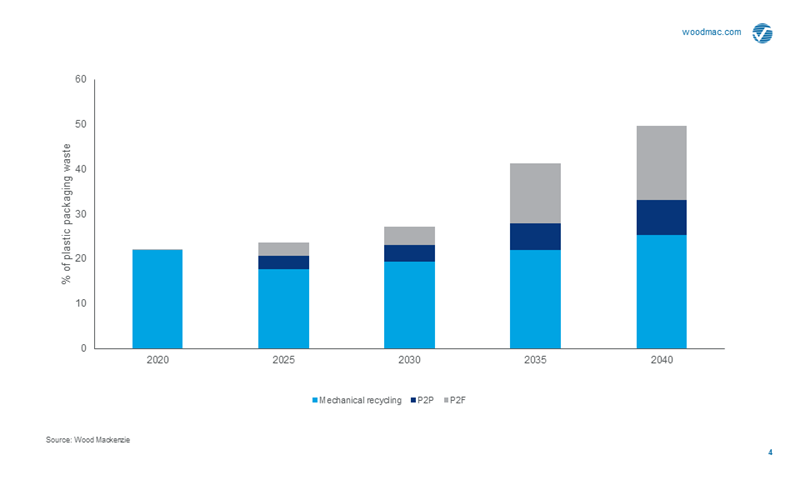

Despite these concerns, chemical recycling’s potential to tackle end-of-life plastic is highly anticipated by many participants across the value chain. Implemented carefully and alongside mechanical recycling, it can increase processing capacity and the value of recycled plastic waste. Our modelling suggests that the proportion of plastic packaging reprocessed into the energy and petrochemical value chains could more than double, from 22% today to 50% by 2040.

Chemical recycling could boost the global plastic packaging recycling rate to 50% by 2040

But how does chemical recycling go from a potential game-changer, to making a material impact?

The full report explores the hierarchy of waste disposal methods, how chemical recycling technologies can be scaled up to become commercial, and the major challenges that lie ahead. The report also includes charts on the projects tracked in our chemical recycling database – and the technologies attracting the most attention.

Fill in the form at the top of this page for a complimentary preview.