Future energy – green hydrogen

Could it be a pillar of decarbonisation?

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

US Lower 48 upstream: the US Majors’ long-term strategic advantage

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

The ambition is net-carbon neutral. The EU, and others, want to get there by 2050, some even sooner. Achieving that goal needs policy, investment and technology. Hydrogen is one of the technology pillars on which hopes to abate climate change rest. To find out more, I chatted to Ben Gallagher, our lead analyst on emerging technologies.

What is the attraction of hydrogen?

It's a super-versatile energy carrier with exceptional energy density (MJ/kg). Today, around 70 million metric tonnes of hydrogen are produced globally, used across an array of sectors – fertiliser, refining, petrochemicals, solar panels and glass manufacturing. In the future, hydrogen will have a huge role to play in decarbonising the global economy, especially in hard-to-decarbonise sectors. But, first, there are a lot of challenges.

How is hydrogen produced today?

The technology is entirely based on fossil fuels. Around 71% is ‘grey’ hydrogen (steam methane reformation, or SMR) while most of the rest is ‘brown’ hydrogen (gasification of coal or lignite). These processes have been around for decades. The challenge is dealing with the carbon and high emissions that result. The future for the current technology is all about ‘blue’ hydrogen, where the production process is paired with carbon capture and storage (CCS). But CCS isn’t yet widely commercial and needs scaling up, too.

Grey, brown, blue – what about green hydrogen?

The technology is different, with the hydrogen produced from water by renewables-powered electrolysis. The process is zero carbon and gives very pure hydrogen, whereas grey or brown hydrogen contains impurities. The idea is that green hydrogen piggybacks on the rapid roll-out of renewables in the coming decades. As penetration of intermittent solar and wind generation into power markets rises, system prices will fluctuate and generally should be lower. When there’s surplus renewables, prices will drop, becoming cost-effective for green hydrogen. The hydrogen can then be sold or stored until it’s needed. Green hydrogen therefore becomes both a form of energy storage and a balancing tool for renewables.

What are the uses?

As well as the sectors hydrogen already sells into, green hydrogen’s zero-carbon credentials open a wide range of new ones. Green hydrogen will be critical for difficult-to-decarbonise industries like steel and cement, for blending with methane in gas pipelines (though hydrogen’s low volumetric density poses challenges for existing infrastructure), in fuel cells for electric vehicles and many other applications.

And the economic challenges?

Green hydrogen has to compete with SMR hydrogen, which costs between US$1-2/kg without CCS – or 50 cents more when paired with CCS. These are costs that green hydrogen can’t even get close to currently. Green hydrogen’s economics are particularly sensitive to two factors – power prices and plant utilisation rates. The economics only work on what are unrealistic assumptions today – high load factors (more than 50%) and low electricity prices (below US$30/MWh). But, right now, a green hydrogen plant paired with a renewable source could expect load factors nearer 20%; typically, power purchase agreement prices for renewables are nearer to US$50/MWh globally.

How could green hydrogen become viable?

First, cost reduction – we expect capex to fall by one-third by 2030, especially as the manufacturing process for electrolysers moves to automation, unit feedstock costs reduce by 5% and electrolyser efficiency improves by 8%. But those gains still leave green hydrogen well out of the money.

What needs to change?

The big impetus is likely to be policy and societal desire for change. If, as we expect, national and corporate strategies embrace green hydrogen as part of a strategy to decarbonise, it could take off, driving the economic threshold down. That means investment in R&D, improvements in technology, pilot projects with industrial users and adapting to changing power markets as renewables penetration increases. Carbon pricing will be key – we estimate a carbon price of US$40/tonne in 2030 could get green hydrogen on a level with SMR-produced hydrogen paired with CCS.

When?

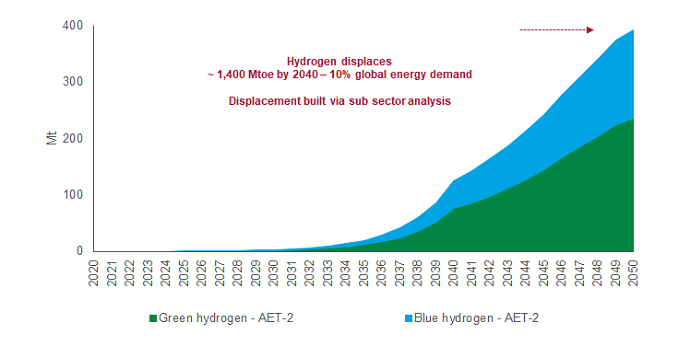

Realistically, it’ll be another decade before hydrogen starts to make a meaningful contribution to decarbonisation. Today green hydrogen is tiny, with only around US$365 million invested in 94 MW of capacity, though the pipeline of new projects is 3.2 GW and growing fast. That shows the interest the technology is attracting in China, Japan, the US, Europe and Australia, but so far, it’s only scratching the surface. If the pieces fall into place it could be huge. We think hydrogen could displace 1400 Mtoe of primary energy demand by 2050 under a 2-degree scenario, 10% of global supply, with green hydrogen the majority of that. Scalable, commercial green hydrogen would answer a lot of questions around global decarbonisation.

And who will invest?

Only a handful of companies have entered the electrolyser market. But rising membership of the Hydrogen Council, formed in 2017, reveals the widespread interest among big players across multiple sectors including automakers (among them BMW, GM and Honda), power and gas utilities (Engie and EDF), engineering (Bosch, Alstom), finance, and oil and gas (Aramco, Shell, BP, Total and Equinor).