Securing exposure to Permian tight oil – Part 1

Reasons to invest

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

What do Total, BP, Eni, CNPC, Sinopec Group have in common? Each is among the biggest oil and gas producers in the world, with a portfolio diversified geographically and across multiple resource themes.

Yet none has meaningful exposure to US tight oil or to the Permian Basin, with its giant inventory of low-breakeven, yet-to-drill wells. It’s a significant gap in optionality. BHP Billiton’s sale of its suite of US onshore assets this summer will have attracted multiple bids.

Some of those listed question the tight oil value proposition and may not participate. Tight oil incumbents are expected to dominate the bidding, but there are plenty of new entrants alive to this and other opportunities.

It’s worth assessing the pros and cons of getting into US tight oil at this stage of its development. I kick off this week with the pros, chatting to R.T. Dukes, Head of US Lower 48 Oil Supply.

First, the growth potential.

Nowhere on the planet has liquids growth of this scale over the next ten years and capable of providing materiality to any portfolio.

US tight oil production is poised to climb from just below 6 million b/d this year to 10 million b/d by the late 2020s by our forecasts.

From now on in, the Permian is the big engine, providing 3 million b/d or 80% of that growth. Some operators’ forecasts are 1–2 million b/d more bullish.

The Bakken and Eagle Ford, the other big US tight oil plays, are further down the track in terms of development and are already showing signs of flagging growth. We expect tight oil production outside the Permian to put on another 1 million b/d, reaching a plateau of 4.6 million b/d in the early 2020s.

The Permian is much bigger in areal extent, and has thicker formations with multiple benches at a much earlier stage of development.

By 2024, Permian volumes will exceed the rest of tight oil combined, and though the rate of growth slows, never looks back.

The next stage for the Permian is about enhancing recovery. Development is being industrialised, with ExxonMobil, Chevron and Shell now among the biggest investors shaping the way the basin is being exploited. ‘Cube’ and ‘tank’ strategies will optimise well spacing, lateral reach and targeted drilling.

Technology is speeding up the drilling process, where simple changes like slim-hole designs can increase drilling speeds and lower costs. Big data, analytics and real-time feeds are improving the understanding of reservoir delivery.

Second, it’s long-life, short cycle.

Oil and gas companies are still governed by financial discipline and loath to commit to large, high-capital-intensity conventional projects.

Drilling tight oil wells en masse in the growth phase is capital-intensive, but the key difference is that investment can be turned on and off depending on price and margin, and cash is generated quickly from each well.

It’s a different profile from sanctioned, conventional projects with the commitment to upfront spend and a longer wait until payback.

Third, liquidity – to access assets, build a business and, if need be, to exit.

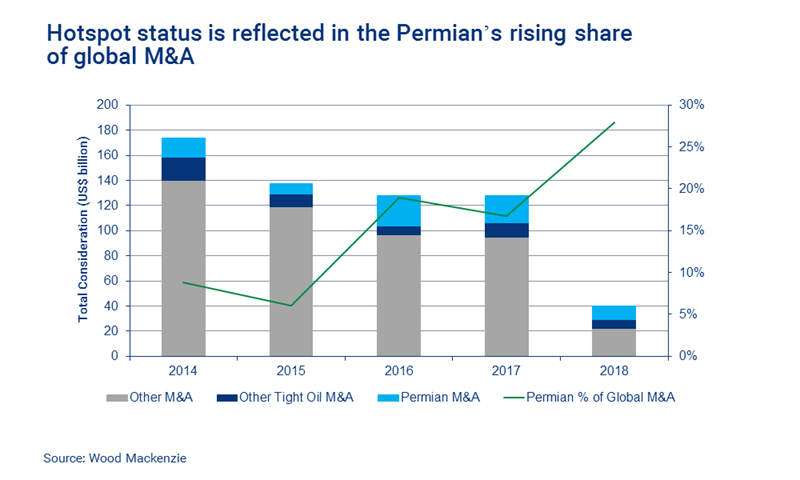

US$57billion in Permian deals has been done in the last three years – 20% of total global M&A spend, and twice as much as other tight oil plays combined.

Yet it’s still a fragmented market, with more than twice as many publicly listed operators than either the Bakken and Eagle Ford, and three hundred other players that have drilled wells. There are multiple ways in – acquisition, partnership, JV or through a private equity vehicle.

Fourth, the skill set.

New entrants need not start out with the tight oil skill set; everything through the value chain can be outsourced. Internal understanding and skills can be built up over time.

The US is the current working laboratory, other plays will emerge elsewhere. Having the know-how, the technology, the processes will equip a new entrant with the wherewithal to transfer acquired skills to any new play internationally.

We’ll tackle the cons next – the risks, the downsides, the valuations.

Hotspot status is reflected in the Permian's rising share of global M&A