What’s holding back a new investment cycle?

Despite healthy cash flow, investment is still in a trough. Simon Flowers looks at reasons why.

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

US Lower 48 upstream: the US Majors’ long-term strategic advantage

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

How the downturn thinned out the upstream opportunity set

We’ll all look back at 2018 as a golden year. Oil and gas companies are raking it in with Brent set to average near US$75 per barrel and cost bases set at US$50 per barrel post-downturn. The best part of US$160 billion of free cash flow will flow into the coffers of the 48 IOCs and NOCs covered in our Corporate Service this year. The money is real enough, but it would be wrong to see the windfall as indicative of an industry in robust health. Investment is still in a deep trough.

I asked Norman Valentine, director of corporate analysis at Wood Mackenzie, what the prospects are for a new investment cycle kicking off.

So Norman, is global upstream investment picking up?

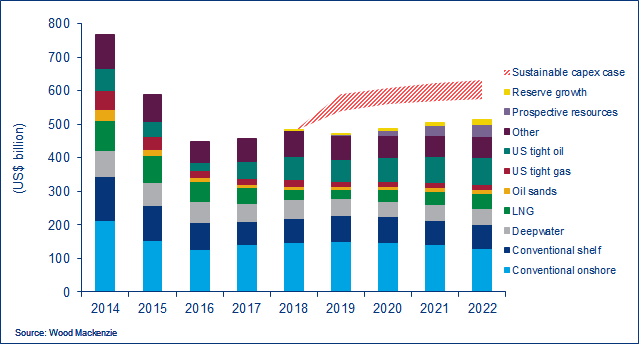

Yes, but the recovery is much slower and shallower than past upcycles. Our analysis shows investment rising from the lows of US$460 billion in 2016 to just over US$500 billion in the early 2020s – way below the US$750 billion peak in 2014. It’s also patchy across the sub-sectors. Only US tight oil looks set fair for consistent growth in investment in the next few years driven by the Permian, and there’s a new wave of big LNG projects coming.

Elsewhere spend is ticking up but there’s no momentum. We think investment in conventional, deepwater US shale gas and oil sands will be stuck well below pre-downturn levels for the foreseeable future.

Aren’t new project sanctions rebounding?

Yes, we’re on course this year to get close to pre-downturn numbers of 40 final investment decisions per year but scale has been sacrificed. Today’s new projects are much smaller, with capital spend averaging US$3 billion compared with US$9 billion a decade ago. And resources sanctioned per year are around 10 billion barrel of oil equivalent (boe), down from 50 bn boe in 2010. The average break even price for projects going ahead in 2018 is US$35 per barrel, reflecting demanding hurdle rates that defeat the bigger and more complex projects.

And the right level of investment?

Around 20% higher, or around US$100 billion per year more. That would take annual spend to US$600 billion – what we think is needed to meet future demand for oil and gas through next decade. It’s below pre-downturn spend because we take into account the progress the industry’s made in reducing costs for the present batch of commercial projects.

What’s holding the industry back from spending more?

Confidence is a big factor. The industry is plagued with doubts as to whether the higher oil price will hold up. The energy transition is also clouding the picture for longer term investment. And companies are stuck in a mind set of austerity designed to appease shareholders – investment is lower in the pecking order for surplus cash flow than dividends and buy-backs.

Will we see a bolder approach going forward?

You’d expect to, but the opportunity set of conventional projects is quite thin. We hold around 100 billion boe in our pre-FID hopper which sounds a lot, but it’s only around two years’ worth of global oil and gas production. Companies have been cherry-picking the best conventional projects: half of our set of pre-FID resources are higher cost projects, uneconomic below US$60 per barrel. On top of all that, risk aversion for the last four years has severely limited resource capture, and there’s been nothing like enough coming in to replenish the hopper.

What are the implications for oil and gas markets?

There’s a risk that we are sleepwalking into a supply squeeze in the middle of next decade. The emergence of US tight oil has brought welcome diversification of supply into the market. But it has effectively sidelined much of the activity in resource capture and development in the conventional world. That will become a problem when, in time, US tight oil can’t on its own meet incremental demand or falls short of expectations. Some argue that OPEC needs to manage the oil price back down from US$80 per barrel. There’s an argument it may need to be higher still to spark investment and for the industry to begin building a stronger pipeline of commercial options for next decade.