5 ways exploration benefits upstream emissions intensity

Analysis of 2014-2023 discoveries by the oil and gas majors shows they are significantly cleaner than the sector average

3 minute read

Xin Yi Dong

Research Analyst, Upstream

Xin Yi Dong

Research Analyst, Upstream

Xin primarily covers Canada and Alaska upstream.

Latest articles by Xin

View Xin Yi Dong's full profileThe Majors have made significant strides in reducing emissions over recent years. Decarbonisation work and portfolio reshaping have been key factors in bringing their emissions intensity figures well below the average for the sector. But how big is the emissions advantage for Majors’ new discoveries, and what factors affect their relative emissions intensity?

Our report ‘Emission intensity benefits of exploration’ uses our Lens Subsurface tool to analyse the emissions profiles of the Majors’ conventional discoveries from 2014 to 2023. Fill out the form at the top of the page to download an extract of this insight, or read on for five key facts from the report.

1. New discoveries made by the majors emit half the global average CO2e

Our analysis found that supplies of oil and gas resulting from exploration by the Majors between 2014 and 2023 have half the emissions intensity of supplies from the average upstream asset globally. These discoveries emit 20-30% less carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) on average than the overall portfolios of which they are a part. For one firm, this has resulted in a reduction in total portfolio emissions intensity of 15%.

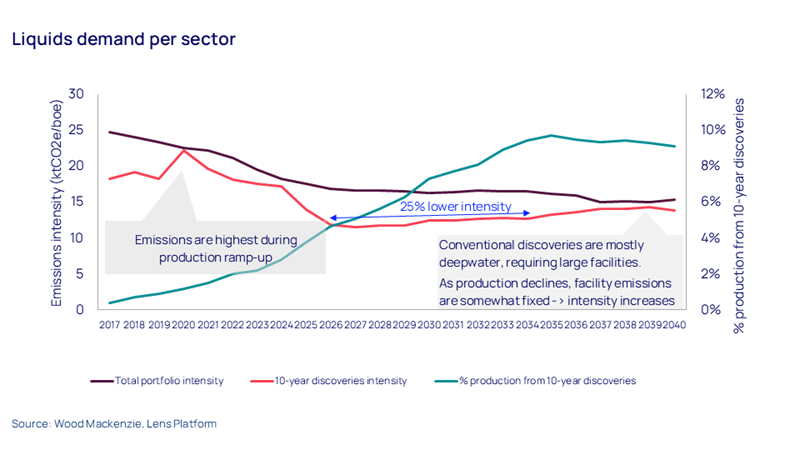

Upstream emissions intensity peaks when production is ramping up, before falling as production volumes increase. Facility emissions are broadly fixed, so emissions intensity tends to rise again somewhat as production declines towards the end of a project’s lifespan (see chart below).

2. Pre-2019 discoveries are more carbon efficient than more recent finds

Majors began to focus on prospects with a lower carbon footprint from around 2018. It would therefore be reasonable to expect that later discoveries made after this change of approach would be lower intensity. Our analysis shows, however, that pre-2019 discoveries are more carbon efficient than those from 2019 to 2023. The reason is that these earlier finds have better reservoir quality, resulting in highly productive wells, which in turn lower emissions intensity.

3. Projects with pre-2020 FIDs outperform those with later FIDs

Development teams began to engineer for decarbonisation from around 2018. As a result, projects sanctioned from 2020 onwards should have lower emissions ‘built in’. Somewhat counterintuitively, our analysis shows that projects that received a final investment decision (FID) before 2020 tend to outperform those with later FIDs on emissions intensity, thanks again to quality. However, it makes sense to focus decarbonisation efforts on newer fields that have a longer remaining lifespan, so these later fields may be good candidates for the addition of carbon reduction technology that will lower their emissions.

4. Large discoveries are more emissions efficient than smaller fields

Thanks to efficiencies of scale, we would expect larger fields (defined as those holding recoverable reserves of more than 100 million barrels of oil equivalent) to emit less CO2e than smaller projects. These large standalone developments must meet strict carbon criteria and can be customised with innovations such as power from shore or electric floating production storage and offloading (FPSO). By comparison, smaller fields that tie back to existing infrastructure are subject to the age and relative inefficiency of their hosts. Our analysis shows that this principle tends to hold for most Majors, with emissions intensity for larger fields lower for four out of seven firms.

5. Deepwater fields typically have lower emissions intensity

Alongside discovery size, water depth is a better indicator of lower emissions than discovery or FID date. Deepwater reservoirs tend to be of good quality, resulting in higher well productivity. As a consequence, fields at a depth of above 400 metres have lower intensity than onshore and coastal shelf finds for all but one of the Majors.

Finally, it should be noted that the exploration advantage in relation to emissions isn’t static; ongoing technological advances and the sustained focus on lowering carbon intensity will mean the emissions performance of new discoveries will continue to improve.

To learn more about how Lens Subsurface can inform investment decisions and help build a resilient portfolio, visit the product page. Don’t forget to fill in the form at the top of the page to download an extract of this insight.