Conventional exploration – playing devil’s advocate

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

Resource yield in decline as tight oil booms

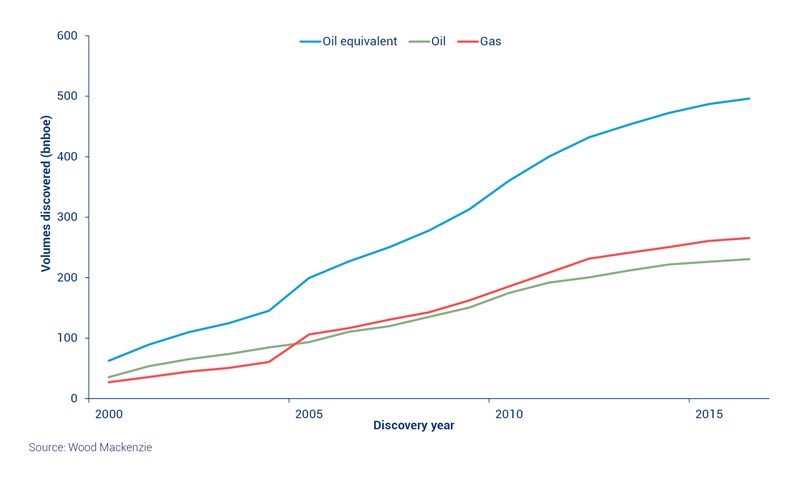

The ‘creaming curve’ is a touchstone of strategic planning in any exploration team. To the layman, it’s the cumulative volumes of oil and gas discovered and indicates basin maturity.

Andrew Latham, our Head of Exploration Research, has built a global creaming curve (below) for conventional exploration outside the USL48. Three themes stand out.

1. Prospectivity is maturing

If not approaching its twilight years, global exploration potential is sporting tell-tale signs of middle age. Discovered resources per well drilled have so far averaged 21 mmboe this decade. This is far below the halcyon days of the 1960s and 1970s (50–60 mmboe per well) when new offshore technology such as seismic and deeper water rigs opened up many basins to wildcatting. But it is reasonably respectable compared with the average of 24 mmboe per well in the four decades since 1980.

2. Recent performance is a concern

Total volumes discovered plunged to a paltry 9 bnboe in 2016, the lowest annual yield in six decades. The new resources found by the drill bit in 2016 are just 23% of last year’s global production, compared with the average of 60% since 2000.

Last year was also the sixth consecutive year of decline. The falling annual volume tips the global creaming curve onto a new, shallower trajectory.

The industry has delivered more than 30 bnboe in a single year only six times since 2000, most recently in 2012. We don’t expect that level to be achieved regularly again.

Belt tightening since 2014 has led to high grading — fewer wells and lower risk prospects. The early results show promise. Volumes per well in 2016 were 21 mmboe, up 36% on the abject lows of earlier this decade. The industry is recognising the need to address declining technical and economic performance from exploration.

3. The recent pre-eminence of gas

Oil consistently contributed the bulk of new volumes right up to the early years of this century. Discoveries of oil in the Atlantic deepwater golden triangle of Angola, Brazil and Nigeria marked a purple patch that culminated in the emergence of Brazil’s giant pre-salt fields in 2006–2010.

Two new plays have been opened up in the last two years, showing that there is still potential for big oil discoveries. Onshore Alaska and ExxonMobil’s deepwater Guyana discoveries hold 4 bn barrels and 2 bn barrels (plus 3 tcf of gas) respectively. But these cannot disguise the broader trend.

Around 500 bn boe have been added to the creaming curve since 2000, more than half gas (53%). The ratio has been increasing, averaging 56% since 2010.

Three mega deepwater gas plays have emerged in the last 10 years. The Eastern Mediterranean has 60 tcf of gas (10 bnboe) across Israel, Egypt and Cyprus, more than half in Eni’s Zohr field. East Africa has over 160 tcf (27 bnboe) in Mozambique and Tanzania. NW Africa, now holds over 35 tcf (6 bnboe) in Mauritania and Senegal including BP and Kosmos’s latest Yakaar discovery.

Is gassy success in exploration a problem? Up to a point in that oil is typically quicker to commercialise and can be higher value per barrel. But gas too has its attractions as a long life resource with stable, predictable cash flows. Gas’s rise is also opportune as upstream companies begin to adapt to a lower carbon future.

Dwindling volumes of oil discovered have coincided with the emergence of huge US unconventional resources. Tight oil will meet virtually the entire global supply gap we forecast over the next few years.

Indeed our modelling suggests that the market’s need for production from new conventional discoveries could be vanishingly small, even on a 10-year view.

A devil’s advocate might ask a few pertinent questions. Is conventional exploration worth the money? Can explorers ever deliver full cycle value tested against lower-for-longer price decks? Does the business model still work?

Three simple responses: The Guyana discoveries are proof that big oil prospects are still out there, and that frontier exploration can not only pay off, but also push tight oil volumes to the right.

Eni’s swift commercialisation of Zohr shows the potential scale and value in conventional gas.

Last, exploration is a long game. Tight oil won’t grow forever, and the seeds of future conventional exploration success need to be sown now.