Future energy – carbon capture and storage

Central to decarbonisation strategies

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

US Lower 48 upstream: the US Majors’ long-term strategic advantage

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

Shell, Repsol, BP are among those setting bold targets to become net-carbon neutral. Governments, too, will head in that direction. But how to get there? Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is invariably central to the strategy. I asked Ben Gallagher, lead analyst on emerging technologies and author of a new report on CCS, about the opportunity and the challenges.

What is CCS?

A method of removing the carbon dioxide (CO2) released in the processing or combustion of hydrocarbons. CCS can be applied in power generation, natural-gas processing, refining, cement, hydrogen reforming and chemicals and other industries. There’s now a search underway to use the carbon or embed it in materials – what’s called carbon capture utilisation and storage.

Complete the form on this page to download the Carbon capture and storage 2020 executive summary and report brochure.

Why is there so much interest in CCS?

Few think the global economy can thrive for the next few decades without coal, oil and gas. The world will be emitting carbon for decades yet; the trick will be to capture and store it. Commercial, scaled-up CCS means we can use fossil fuels while greatly reducing CO2 emissions until energy consumption is fully decarbonised. It’s going to be hugely important for hard-to-decarbonise sectors like cement and steel.

How is CO2 captured?

There are four main processes, each with its own complexities. First, pre-combustion. A gas mix of hydrogen and carbon monoxide (CO) is processed converting the CO into CO2. The CO2 is then removed using solvents.

Second, post-combustion. Sulphur and nitrogen-based gases and any trace metals need to be removed. The residual flue gas is then heated and treated with solvents, releasing CO2.

Third, there’s oxy-combustion, where enriching the fuel-burning process with oxygen gives a higher concentration of CO2 in the flue gas. Lastly, there’s direct air capture, a nascent technology that removes CO2 from the atmosphere. It’s very energy-intensive but may play a part longer term.

How is the carbon stored?

In the many depleted oil and gas fields around the world, with the CO2 transported by pipeline. The Global CCS Institute reckons there’s almost 400 years’ worth of storage capacity at today’s level of annual emissions – more than enough to meet the Paris climate targets. Geological stability is among the environmental criteria for this to work. There are also long-shot contenders for storage – such as low-grade coal seams and saline reservoirs.

Could the carbon be used?

Yes – to enhance oil and gas recovery, extending the economic life of a productive reservoir. New concepts being considered include: embedding CO2 in concrete and other building materials; purifying it for carbonation; transforming it into polyurethanes for use in home furnishings and other materials; and turning it into food products.

What are the challenges?

The idea of CCS has been around for decades, but it still hasn’t really got off the ground. We reckon 68 projects have started and terminated, primarily because CCS is very expensive. Costs are difficult to get a handle on because no project is the same, and a lot of technology is proprietary.

Instead we look at ‘cost of CO2 avoided’ – the carbon price that makes a project economic. We estimate that a minimum carbon price of US$90/tonne is needed for most applications, about three times today’s traded price in Europe. Costs do vary widely – some power projects might make money below US$50/tonne; in difficult-to-decarbonise sectors like steel, it’s up to US$120/tonne; and cement up to $194/tonne.

Costs need to come down. R&D will help, as will, in time, scale and a modular, standardised approach. But CCS also needs fiscal support – as with tax credits in the US recently – and it needs access to low-cost finance so investors can generate an adequate return on equity.

How much investment is needed?

Today, it’s a tiny part of the decarbonisation story – the 42 million metric tonnes of installed capacity are capable of capturing just 1% of annual global emissions. Most are attached to power plants. We think capacity will double by 2030. As the power sector transitions to renewables, blue hydrogen production makes up an increasing proportion of the CCS development pipeline.

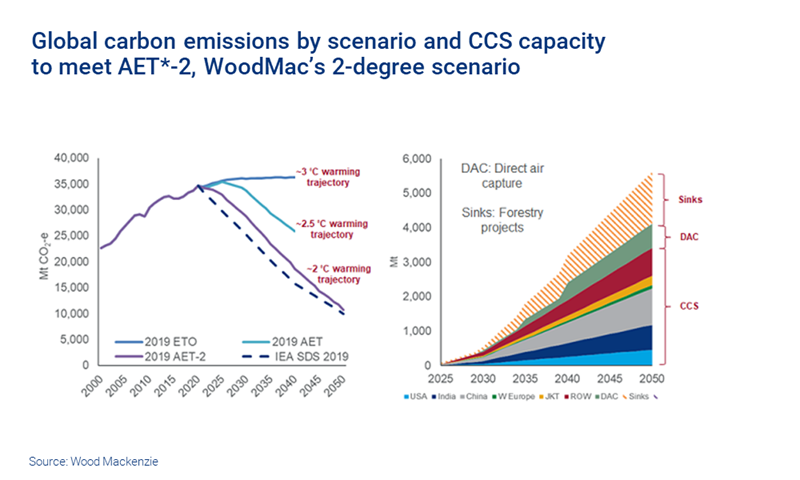

If the world is to get onto a 2-degree pathway, we could need up to 4 billion tonnes of capacity by 2050, 100 times what we have today. Exponential growth will require exponential investment. That will only happen if the incentives are there – high carbon prices, policy support or, most likely, both.

How will Big Oil invest in CCS?

First, storing carbon extracted from high CO2 gas fields – Chevron (Gorgon, Australia) and Equinor (Sleipner and Snovhit, Norway) have projects already in operation.

Second, injecting post-combustion CO2 to enhance oil recovery – Occidental is one of the leading exponents in the Permian.

Thirdly, and a big growth opportunity, is to partner in high-emitting but hard-to-decarbonise sectors. Total has teamed up with Lafarge and Svante in Canada to pilot CO2 capture and reuse from Lafarge’s Richmond cement plant in British Columbia.

Get weekly insights from our chairman and chief analyst, Simon Flowers, on the issues shaping your industry. Sign up for The Edge here.

Want to learn more about the new report, Carbon capture and storare 2020? Complete the form at the top of the page to download the executive summary and report brochure.