Have we passed ‘peak growth’ for tight oil?

What it means for OPEC+ and Permian pipe owners

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

Has US oil production growth hit the buffers? Supply has boomed over the last decade, disrupting the market, domestically and internationally. But weak commodity markets and corporate strategies are now taking their toll, undermining the expected growth path in the near term. I spoke with our North American market expert, John Coleman, principal analyst, crude supply and infrastructure, to get his perspective.

The big question is: have we passed ‘peak growth’ for US tight oil? Our forecasts suggest we have. And pipeline developers (and their financiers) who’ve done so well out of the boom are increasingly concerned about it.

Permian crude supply growth, the main driver of tight oil growth, has outpaced takeaway capacity frequently in the last few years. When production jumped by an astonishing 1.7 million b/d in the two years from January 2018 to December 2019, infrastructure was stretched to the limit. Producers had to fight to get their crude to market. Those without access to pipe had to put crude onto rail or trucks or leave it in the ground. And they paid a high price – the US$10 to US$20/bbl discount at the Midland trading hub only a year ago reflected the cost of shipping the marginal barrel to Houston.

Producers losing out on value while mid-stream asset owners made hay was a constant narrative in tight oil’s first decade. But things have changed. The playing field has tilted decisively in the other direction at the very start of the 2020s. Overbuild means pipeline owners face intense competition for increasingly scarce barrels.

Producers losing out on value while mid-stream asset owners made hay was a constant narrative in tight oil’s first decade. But things have changed.

Permian production growth is decelerating rapidly. Independent producers, constrained by capital discipline, have cut drilling rigs and are shifting focus from growth to generating free cash flow. That will progressively show through in production. We expect Permian tight oil production to increase by just 0.6 million b/d from January 2020 to December 2021 – a fraction of what we saw in the two prior years.

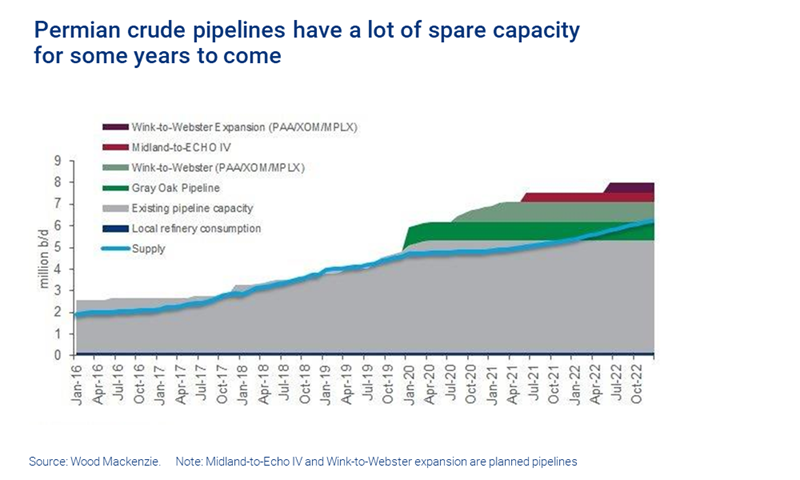

Meanwhile, new pipe is belatedly coming onstream, and at a much faster rate than supply. Capacity already exceeds today’s production of 4.7 million b/d and will reach 7 million b/d by the end of this year. Utilisation rates are down from over 100% a year ago to 85% and fall as low as 68% by mid-2021 in our forecasts. Discounts at Midland have unwound to just US$1/bbl. The value has swung back in favour of producers rather than pipe owners.

The tougher financial climate has forced pipeline developers themselves to embrace capital discipline. We’re seeing strategies shift away from new build to focus on project consolidation and cash generation. These companies intend to reduce financial leverage and return any surplus capital to shareholders.

One big question for them is when the 2.3 million b/d of spare Permian pipeline capacity will be filled. It will take some years. At WoodMac we think Permian supply growth starts picking up again in 2022, and that we could be back at high utilisation rates by 2025. There’s plenty of tight oil inventory. How quickly it’s developed depends on price and whether corporate strategies shift back to growth. But there’s a possibility the Permian may never need another new pipeline built.

Our oil market expert, Ann-Louise Hittle, points out that there are also big implications for global oil markets. OPEC+ has its work cut out to balance the market in 2020. Demand is weakening – early in February we revised down Q1 demand by 0.9 million b/d, and calendar 2020 by 0.5 million b/d, mostly due to the effects on the global economy of coronavirus, especially in China. We expect full year demand growth of about 1 million b/d.

Non-OPEC liquids supply is set to grow at more than twice that rate, by around 2.4 million b/d, much the same as it has for the last two years. What’s different in 2020 is that growth is split evenly between the US and other non-OPEC producers including Norway, Canada and Brazil.

OPEC+ has a full ministerial meeting scheduled for 5-6 March. As it weighs up how much more production to cut – if any – it will find that for the first time in several years, US tight oil growth is not the biggest of the problems it’s facing.