How solar is central to the energy transition

Decades of growth in power and green hydrogen

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

Solar is king of the low-carbon technologies. Its new-found competitiveness makes solar central to decarbonising power markets and, in time, it can fuel green hydrogen’s push into hard-to-abate sectors. I chatted to Ravi Manghani, Head of Solar, who forecasts in Horizons that solar costs will continue to fall.

What’s driving the growth in solar?

It’s economics rather than just the environmental agenda – solar is now competitive. Solar costs have fallen by 90% this century, most of that in the last decade. Nearly all capacity installed until now has been supported by feed-in tariffs and power purchase agreements subsidised by governments, in many cases, to get renewables off the ground. The guarantees attracted the capital, which delivered the scaling up. That’s all led to a steep reduction in costs.

We’ve reached the point in 2021 where, without subsidies, solar is cheaper than any other technology in 16 US states and some markets elsewhere in the world. Solar will dominate new power capacity as the world electrifies with as much as 8,000 GW added by 2050 in our AET-2 scenario – twice as much as wind (AET-2 is WoodMac’s 2 °C energy transition scenario).

Can costs fall further?

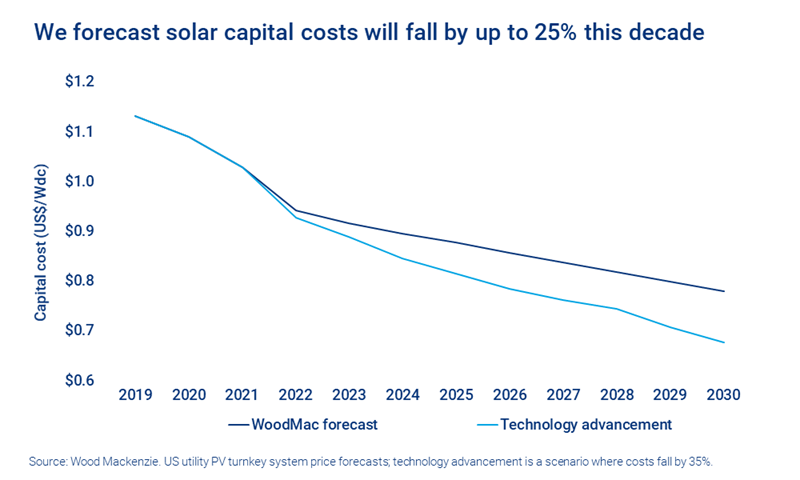

We think we’ll see another 15% to 25% reduction over the next 10 years from a host of technology innovations. Two stand out. Bi-facial modules, which allow electricity generation on both sides of the panel, could lead to efficiency gains of up to 15%; and increasing wafer size on the module from the 158 mm in use today to 210 mm could double the power rating.

There are also big gains to be made from operational improvements. Tracker technology to align the panels with the sun as it moves through the day can increase generation capacity by up to 25%. Bigger inverters are also coming and can reduce the overall project footprint, while solar projects have yet to reap the efficiency gains from automation, digitalisation and application of artificial intelligence. We expect continued cost reductions will make solar competitive at wholesale prices in most power markets by 2030.

Will cheap solar drive power prices down?

Yes. The two will go hand in hand, pushing more expensive coal and other thermal generation out of the market. Solar’s competitiveness rests on continued cost improvement so that margins stay robust even if wholesale prices fall. We’re starting to see developers build projects based purely on selling the power into the wholesale market.

Problems arise when solar penetration reaches a double-digit percentage of generation in any market. At that point, the ‘duck curve’ effect can kick in. Power prices are depressed during the day when solar is producing, bouncing back when the sun sets and solar is offline, so flexible plant is brought on to meet peak demand in the evening. The duck curve is punishing for solar revenues.

What can solar producers do about the duck curve?

Build battery storage, a technology that’s going to get much bigger. We are already seeing developers include battery storage in their interconnection queue applications. The plan is to mitigate lost revenue by storing ’cheap’ power during the day and dispatch it at peak prices in the evening.

Do customers buy solar directly?

More and more. Since 2019, it’s surpassed wind as the technology of choice. Data centres and technology companies led the way, and now we’re seeing industrial and retail off-takers join in. Unlike utilities, which typically commit to long-term contracts, these buyers tend to want shorter-term contracts. That will tend to accelerate solar developers’ exposure to merchant markets.

Was solar to blame for last month’s Texas power crisis? No, there were several systemic failures in power supply in this extreme weather event but solar was peripheral, to say the least. There’s very little solar on the Texas grid today – in December 2020, just 6 GW of installed utility solar, so 5% of the market. And while solar is intermittent unlike wind, it’s fairly predictable.

As renewables’ share of a power market grows – in Texas alone, there’s over 90 GW of utility solar in pipeline – there needs to be a multi-faceted approach to deal with intermittency and one-offs, such as a Texas-style event. That will include building in diversity of supply and ensuring flexible and back-up capacity, including energy storage, is adequately rewarded; as well as demand management.

What’s the opportunity for solar in green hydrogen?

The next two decades are about power markets, but green hydrogen holds the promise of a second wave of potential growth for solar in the mid-2030s. Green hydrogen will play a big role in the transition as a long-duration storage and grid flexibility solution. There are many hurdles before hydrogen can fill that gap; not least, harmonising variable renewable supply. If it happens, it will open up new revenue streams for solar asset owners selling excess hydrogen to industrial clients in hard-to-abate sectors.

The opportunity goes beyond the domestic market because hydrogen is transportable in liquid form. High irradiation countries will use solar to fuel electrolysis and export the hydrogen or its derivatives.