Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

The mounting challenges facing Europe’s power market

Will the energy crisis be a catalyst for structural change?

5 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

The power sector finds itself at the focal point of multiple, building pressures with the threat of chaos looming over the European energy market this coming winter. The energy trilemma – security, sustainability and affordability – was always anticipated but most observers expected it to play out over years, even decades. The present crisis means governments, regulators and the industry must deal with it right now. I asked Peter Osbaldstone and Dan Eager of our Power and Renewables team for their latest thoughts.

Why are power prices at record levels?

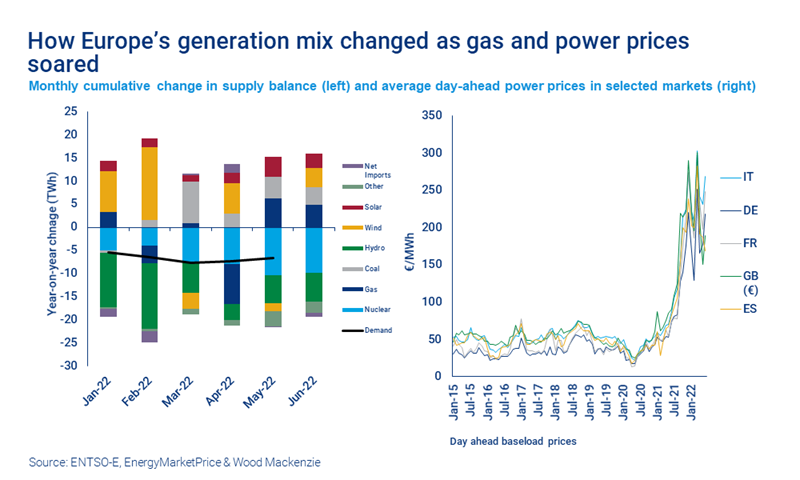

High gas prices are the big factor, though far from the only one. Gas-fired generators provide Europe’s marginal power supply: power prices move up and down with gas prices. Gas pipeline imports from Russia are 55% down year-on-year and that’s sent gas and power prices through the roof.

But there are numerous other challenges in the power sector that are also pushing prices up: high coal and carbon prices, low hydro availability, low river levels in Germany putting coal deliveries at risk and reduced availability across the ageing French nuclear fleet. Europe’s current heat wave has boosted electricity demand for cooling, limited the availability of cooling water for thermal plants and cut the efficiency of system infrastructure.

Day-ahead power prices are high and volatile. Baseload prices for calendar 2023 are trading at over EUR 300/MWh in Germany and above EUR 450/MWh in France. The big fear is more disruption to gas supply this winter. French baseload for Q1 2023 delivery is currently close to EUR 850/MWh.

What are the short-term solutions?

There’s no quick solution – developing new gas supply, building new power capacity or building new interconnection will take years. But there are levers to pull that can lessen the pressure on the market.

First, governments and utilities are scrambling to secure what gas they can to ease tightness in the market. The problem is that there’s only limited additional volumes from indigenous or alternative pipeline suppliers. Existing LNG production is already maxed out, which means paying up for cargoes that were destined for Asia.

Second, power generation must switch away from gas. That means more high-emitting coal (with its own supply restrictions), nuclear and even what little oil plant is functionable; allowing for sustained operation of strategic reserve plant; restarting mothballed plant or postponing closures; and accelerating maintenance schedules. Existing interconnection can move power between markets to where it’s most needed.

Third, demand management. The demand-side in power has been relatively resilient to high prices and is running just 2-3% lower than last year. Governments have already indicated that, in extreme periods this winter, interruptions or selective rationing will be a last resort to ensure supply can be maintained to critical consumers, institutions and industries.

In contrast, we expect gas demand to be 12-15% lower this winter as a result of high prices. The European Commission published a plan this week to “Save Gas for a Safe Winter”, exhorting governments to seek a 15% reduction in consumption.

Are governments dealing with affordability?

Up to a point, yes. All governments recognise they must help consumers, but policies are manifesting in different ways. In Spain, the government has capped the wholesale gas price paid by generators, effectively capping the Spanish power price. In the UK, the government has introduced a package of subsidies and loans for consumers. The European Commission recently granted state aid approval to German plans for a EUR5 billion grant-based scheme to support energy and trade-intensive industries – this is on top of a broader package of tax-based reliefs for consumers agreed in March. In France, the government’s move to take full control of EDF is in part to protect a national champion and critical supplier.

In essence, these solutions, in their various forms, boil down to subsidies or temporary financing. These help with affordability today but, ultimately, consumers will pay.

Will the crisis be a catalyst for structural change in power markets?

Yes, and alternative structures for price setting are already being discussed. The marginal pricing model, for so long the bedrock of liberalised wholesale markets, has worked well for the most part. It was designed as an economically efficient means of power price-setting in a market with a mix of technologies and operating costs. But variable renewable energy, with little to no short-term operating costs, does not fit well into this system. Sooner or later, renewables’ rising share of the market was going to lead to change.

The crisis has exposed how marginal pricing can over-reward all other plants, whatever their costs, fuel or technology. All governments and regulators will be looking closely at this. The UK has launched a review that will look to lessen the influence of gas prices in power and reduce costs to end-users. For the wholesale market, the idea is to split the market in two: one for non-dispatchable sources – such as wind and solar – and the other for dispatchable ones, currently dominated by high-cost gas but, in future, flexible decarbonised alternatives.

How long will prices stay elevated?

The next three to four years. High prices are sparking a flurry of investment in new gas supply, mostly US LNG capacity. But there will only be a drip feed of additional volumes until a wave of LNG from new developments comes onstream after 2025. That’s a turning point and the arrival of additional supply should pull down global gas prices and the whole complex – coal, carbon and power prices – towards pre-crisis levels.

Can Europe’s power sector bounce back from all this?

Yes, REPowerEU confirms that policy commitment to decarbonisation is more bullish than ever. Electrification is at the heart of both energy security and net-zero objectives, and domestically sourced low-carbon power can deliver both. Power markets are set to increase substantially in size, reversing the downward volume trend of recent years. The EU also wants to do it faster – REPowerEU is aiming for the challenging target of 69% renewables in power supply by 2030. It will help that the crisis has made wind and solar suddenly look better value than other options.

There’s no shortage of capital wanting to invest in the growth opportunity in renewables, and the prospect of higher wholesale prices should be a bonus for new projects. However, any changes to the marginal pricing system increase regulatory risk, invariably a dampener for developers.

We will need gas in the power mix for years, perhaps decades. Volumes of unabated natural gas, though, will diminish through time, with flexibility increasingly provided by hydrogen and storage technologies. Whether gas or low-carbon alternatives, flexibility will be priced at a premium.