Why oil and gas exploration is still important

New low cost, low carbon barrels are needed even in a 2 °C world

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

Do we still need to explore for oil and gas? One conclusion in our Horizons scenario analysis is that if the world gets onto a 2 °C pathway, there’s enough oil in existing discoveries to meet future oil demand. It’s a view the IEA NZE concurs with.

Dr Andrew Latham, Huang Tra Ho and Julie Wilson have just published their analysis of the Majors’ exploration performance for 2011-2020. In that tumultuous decade, exploration lost its way economically, before a pivot to value that got returns back to respectable levels – even at US$50/bbl. I asked them where exploration goes from here.

Is exploration still relevant?

It will still play a role in upstream. Even if we do get onto a 2 °C pathway, exploration can deliver new resource into the supply stack that’s lower cost and less carbon-intensive than existing resources. We also think the focus of exploration will progressively shift towards gas, for which demand will be more resilient through the transition.

There is still a likelihood that oil and gas demand holds up for some years. In that case, we’ll want exploration to find new resource to offset the natural decline in production from existing fields.

How committed are the Majors?

They’re spending a lot less on exploration. A decade ago, conventional exploration was central to portfolio renewal and growth. In 2011-2015, the Majors together spent an average of US$16 billion a year on exploration and appraisal. The collapse in oil prices in 2015 led to financial pressures and capital discipline that hit exploration hard. Spend shrank by two-thirds, dipping to just US$5 billion in the crisis of 2020.

For the first time, we’re starting to see differing levels of commitment among the Majors. The energy transition is increasingly influencing investment, and strategies are diverging. Exploration is still core to ExxonMobil, Total and Eni. In contrast, BP has the most aggressive plans to decarbonise its business. It spent just 6% of its upstream budget on exploration in 2020 and may shrink it further. BP is an outlier in radically downsizing upstream, with exploration collateral damage. It could be years away, but eventually others too will wind down upstream and with it exploration.

Paradoxically, the collapse in price in 2015 did exploration a favour.

Does exploration still make money?

It can be very lucrative, even at US$50/bbl. Paradoxically, the collapse in price in 2015 did exploration a favour. Out went capital-intensive, long-payback opportunities; in came short-cycle, quicker-payback prospects. A lot of capital shifted away from conventional exploration to short-cycle tight oil, which has now become Chevron’s main focus.

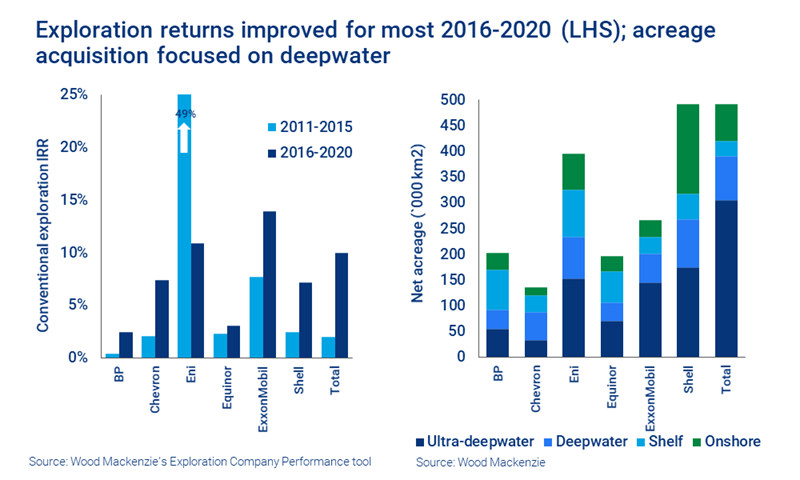

Since 2016, the Majors have drilled fewer conventional exploration wells and concentrated on prospects that could be commercialised swiftly. Six of the seven Majors delivered higher returns from conventional exploration in 2016-2020 than for the previous five years. Eni’s returns fell, but it was from a spectacularly high base of 49% IRR in the first period on the back of its giant 2015 Zohr gas discovery (returns boosted by the post-discovery selldown of equity, which is part of its exploration business model).

The tighter focus has delivered high-value discoveries across a range of plays, including near-field Gulf of Mexico discoveries for Chevron and oil tie-back finds in Angola for Eni.

There are also the game changers, reminders of the what exploration can do, even for a Major. Equinor’s Johan Sverdrup (2010), Eni’s Zohr (2015), ExxonMobil’s multiple deepwater oil finds in Guyana (from 2015) and Total’s giant discoveries in Suriname (2019-2020) have quickly become the jewels in the crown of their upstream portfolios.

Are the Majors still taking on new acreage?

The gathering trend is contraction to core regions and incumbency – there’s less appetite to take on new areas. That said, most of the Majors have reloaded aggressively, even in 2020. Shell and Total are the biggest acreage holders, followed by Eni.

The big attraction is deep water, home to most of the world’s accessible yet-to-find resource and the giant prospects with the potential to create material value. The most contested deepwater hot spots in 2020 were in Latin America (Brazil and offshore Argentina).

Will NOCs step into the gap?

NOCs account for about half of all exploration volumes, the vast majority of resource in their own backyard. Rosneft, TPAO (Turkey), Gazprom and CNPC were in the top six for net resource discovered in 2020. CNOOC’s exposure to the giant Guyana oil finds has made it a rare exception with success on the global stage, as well as offshore China. PTTEP (Malaysia and Mexico) and Petronas (Indonesia, Mexico and GoM) are also breaking through internationally.

Resource-holding governments will want to maximise the value of their oil and gas revenues through the energy transition. If IOCs progressively narrow their geographical focus and keep budgets tight, NOCs will take more of a lead in proving up and commercialising resource.