Discuss your challenges with our solutions experts

1 minute read

Julian Kettle

Senior Vice President, Vice Chair Metals and Mining

We have extracted metals from the earth’s crust for millennia. We’ve converted mined material into primary metal at considerable financial and environmental cost. And yet we only recycle a fraction of the metal that we extract – despite the fact that most can be reused infinitely. Could increased recycling displace our need for freshly mined metal and help save the planet for future generations? Is there enough scrap metal in the system to satiate humankind’s endless demand for more?

Governments are reluctant to put the environment before economic growth but, increasingly, the two will be interlinked. A strong economic rationale exists for greater scrap processing and use. Capital investment costs for scrap processing facilities for aluminium are typically 10% of that for primary and 50% or less for steel. Then there are the carbon emissions benefits – typically, secondary aluminium production has a carbon footprint five to 25 times lower than primary metal production. For steel, the largest industrial emitter, emissions can be halved.

Although scrap demand will outpace growth for primary metal, it will remain underutilised compared to its overall availability. Why? Because price, profit, quality and technological considerations currently drive development of the secondary industry. But stricter environmental policies will change scrap availability and use.

The prospect of a US$110/tonne carbon price will undoubtedly lead to an acceleration of scrap processing in carbon-intensive industries.

One example would be carbon tax policy. The prospect of a US$110/tonne carbon price (Wood Mackenzie’s estimated global carbon price required to limit warming to 2 degrees) will undoubtedly lead to an acceleration of scrap processing in carbon-intensive industries. In contrast, for low carbon-intensive industries, untouched by carbon taxes, uptake in scrap use is likely to be slower and will depend heavily on relative production costs.

Consumer and investor pressures – demanding recycled content – could transform the market but it will not happen until incentives are compelling and quality can be maintained. Policies that mandate greater recycling rates are already driving cleaner and more reusable scrap collection. Furthermore, policies on minimum recycled content could spur demand for scrap. In addition, we believe that governments will increasingly see scrap as a strategic source of low-carbon domestic supply with significant growth potential.

If policy is the key to unlocking scrap availability, how much metal scrap could be recovered? And if all available scrap is recovered will we need to mine metals in the future?

It’s impossible to eliminate the need for the mining and processing of primary metal, even allowing for a massive expansion of scrap availability. Many end uses cannot use scrap while rising demand for metal elsewhere will mean that scrap alone couldn’t fill the gap. Absent seismic shifts in policy and society, scrap will remain underutilised.

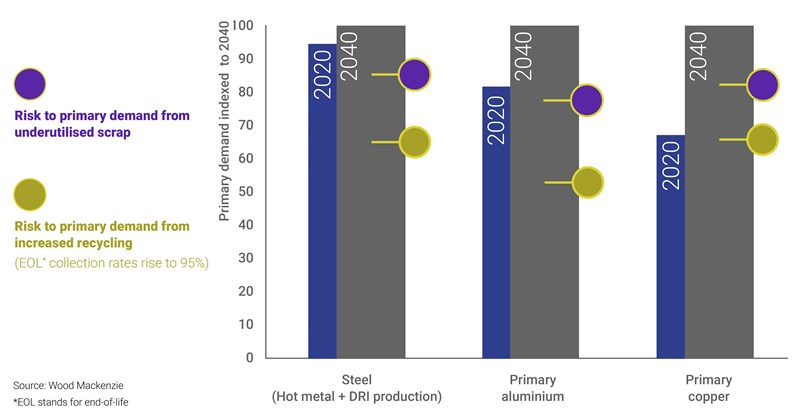

Environmental policy will force a rapid increase in scrap utilisation. By 2040, an extreme environmental regulation scenario equivalent to our AET-2, or 2 °C world scenario, would reduce primary metal demand by up to 35% for iron, 47% for aluminium and 34% for copper. This could prove truly transformative for producers and the planet alike.

The art of estimating scrap availability

We first need to establish levels of scrap availability. This is defined as an unconstrained view of scrap supply potential – a scenario where metal prices, consumer demand and scrap quality don’t matter. In the real world, of course, these

considerations can’t be ignored so scrap availability offers a view of the maximum potential supply.

There are two types of scrap: scrap generated through production processes – semifabricator and fabricator scrap – and scrap recovered from end-of-life goods (old scrap). Calculations of scrap availability depend on five assumptions, which vary for different metals, products, years and countries.