Is Northeast Asia finally tackling its coal dependency as air quality deteriorates?

Concerns over emissions pollution is now driving policy change across Northeast Asia, but responses remain patchy and uncertain

3 minute read

Gavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin oversees our Europe, Middle East and Africa research.

Latest articles by Gavin

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

Upside pressure mounts on US gas prices

-

The Edge

The coming geothermal age

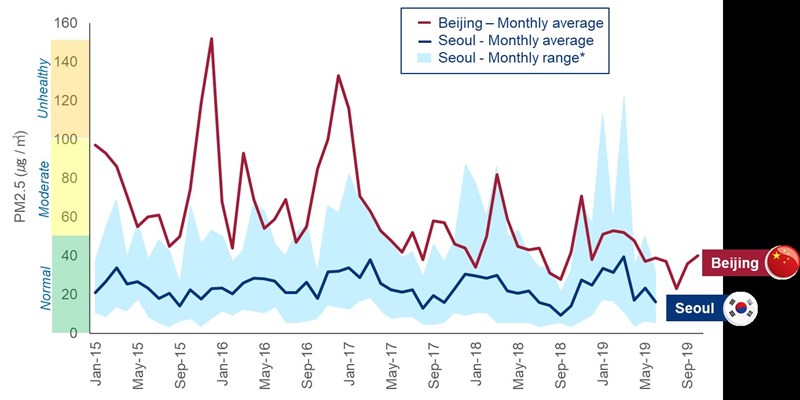

Over the 14 years I spent living in Beijing, the question I was asked most was how I coped with the air quality. Fortunately, Beijing’s notorious pollution never really affected my health (I ran my personal best marathon time in the city in 2014 during some serious haze), and in recent years the city’s government has made major efforts to improve the situation. The result is a marked improvement in air quality.

Credit where credit is due, though clearly policy efforts in Beijing and across China need to continue as I’ve discussed several times in the APAC Energy Buzz. But what about the rest of Northeast Asia? The reality is that much of the region’s air quality has deteriorated over the past few years.

As 2019 ended, I visited clients in Tokyo, Seoul and Taipei and was struck by how rapidly concern over emissions has escalated and is now driving energy policy change. I believe this trend could accelerate in 2020, with important implications for companies and the fuel mix across the region.

As air quality deteriorates, Seoul tackles coal

Guess the city? No, not Beijing or Delhi, this is Seoul in November 2019. Just the kind of conditions that led South Korea’s government to declare a ‘social disaster’ over fine dust particle emissions in March 2019 and to set up the National Council on Climate and Air Quality (NCCA) the following month. The government complemented existing restrictions of coal-fired power plants with additional winter curtailments from the beginning of December last year, targeting a 44% cut in PM2.5 emissions.

With a quarter of South Korea’s oldest coal capacity earmarked for closure over December to February (though there remains no actual data yet to confirm this is happening), with some units also at risk through March. All other coal-fired plants will be capped at 80% utilisation.

It’s also worth noting that 2019’s winter curtailments are only the latest challenge to coal generation in South Korea and follow on from spring restrictions (running from March to June and in place since 2017), and the April 2019 tax reforms, which raised import duty on coal by 27% and reduced it on LNG by 74%. While the exact scale of curtailments and how they will be implemented remains unclear, we see LNG as a winner (and nuclear) as coal demand falls.

Taiwan follows suit

Policy efforts to reduce emissions have also been seen in Taiwan, where state-owned generator Taipower also escalated winter coal restrictions in response to mounting air quality concerns. Initial plans aimed for the shutdown of 2.7 GW of coal this winter, and this has now been extended to a full shutdown of 5.5 GW at Taichung through December and January. As in South Korea, details around implementation are limited, though LNG is intended as the alternative fuel choice.

Tokyo’s plans to tackle coal: big on rhetoric, but light on action

It didn’t go unnoticed that at the UN climate change summit in New York in September 2019, Japan, the country that delivered the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, was not invited to speak due to its continued support for coal-fired power. And while Japan was not alone (Australia for example also never received its invite from secretary-general António Guterres), the gesture highlighted Tokyo’s complex, and often contradictory, position on coal.

Last year, Japan’s government committed to achieving carbon neutrality ‘at the earliest possible time in the latter half of this century’, while also laying out ambitious plans for investments in carbon capture and storage for the coal-fired power sector by 2030. And then there’s the somewhat ambiguous goal to become a ‘hydrogen society’ by 2050. Additional headline grabbers, such as importing the world’s first carbon-neutral LNG cargo, add to the perception of serious steps towards decarbonisation.

But the reality is that coal isn’t disappearing anytime soon within Japan’s long-term energy planning. And while its share of electricity output falls from 33% currently to 27% by 2040, coal maintains its second-place ranking in Japan’s energy mix. At the same time, Japan continues to build new coal-fired capacity (admittedly higher-efficiency) and the country’s banks and overseas development agencies remain active in financing mines and coal-fired plants across Southeast Asia.

To quote my colleague Lucy Cullen, who covers Japan’s energy market, ‘until Japan’s government and METI seriously address the future of coal, the country will not be seen as fully committed or a leader in tackling climate change’.

Read more: Asia Pacific gas and LNG - 6 themes to watch in 2020

Real progress is challenging, but don’t let perfection stand in the way of good

The Beijing city government’s aggressive approach to tackling air pollution is working and South Korea’s spring coal-fired curtailments show some success in cutting seasonal emissions. If winter curtailments have a similar result (and blackouts are avoided during peak demand), then I think it’s realistic to expect that seasonal coal curtailments will become a permanent feature across much of Northeast Asia.

This should benefit LNG, particularly while spot prices remain low. There are still challenges though, as the structure of energy markets in Northeast Asia does not favour significant coal-to-gas switching. But the combination of rising public antipathy towards air pollution and sustained low gas prices could provide the necessary impetus for governments to support policy for wider scale switching in 2020.

If this happens, then the next question is what happens once gas prices recover? It’s easy to be pessimistic but having lived in Beijing for many years, I know that the city’s residents are largely unopposed to paying (a little) more for their energy as a trade-off for cleaner skies. We are all aware that this is taking a little longer in Asia than in other parts of the world, but I think the quote below from Mr Choe Peng Sum, CEO of the Pan Pacific Hotels Group in last Friday’s Straits Times sums up where we are.

"Sustainability is costly, but we have to think long term. People in Europe and America, for instance, are more in tune with saving the environment, but Asia is also coming up now. People will soon demand it from us."

Mr Choe Peng Sum, CEO of the Pan Pacific Hotels Group

Up next

Wednesday 15th January will see all eyes on the signing of the US-China Phase 1 trade agreement. Next week’s APAC Energy Buzz will consider what this means for energy in the region, with my expectations on the low side of very little.

APAC Energy Buzz is a blog by Asia Pacific Vice Chair, Gavin Thompson. In his blog, Gavin shares the sights and sounds of what’s trending in the region and what’s weighing on business leaders’ minds.