Is upstream oil and gas delivering on decarbonisation?

Upstream scope 1 & 2 emissions intensity has been cut by 12% since 2017. But is the industry delivering on decarbonisation?

4 minute read

Fraser McKay

Head of Upstream Analysis

Fraser McKay

Head of Upstream Analysis

As head of upstream research, Fraser maximises the quality and impact of our analysis of key global upstream themes.

Latest articles by Fraser

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: diverging development strategies in Latin America, investment at risk in Africa, and Kazakhstan supply tensions explained

-

Opinion

Is oil price volatility a threat to upstream production, investment and supply chains?

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: UK fiscal changes and an Asia-Pacific licence bonanza

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: the global sanctions slump, grappling with gas and potential US tailwinds

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: the global sanctions slump, grappling with gas and potential US tailwinds

-

The Edge

Why upstream companies might break their capital discipline rules

Adam Pollard

Principal Analyst, Upstream Emissions

Adam Pollard

Principal Analyst, Upstream Emissions

Adam is a principal research analyst leading Wood Mackenzie’s upstream emissions initiative.

Latest articles by Adam

-

Opinion

Video | Lens Upstream: Leveraging emissions and commercial data for decarbonisation

-

Opinion

Is upstream oil and gas delivering on decarbonisation?

-

Opinion

Global upstream update: a review of key industry themes

The intensity (emissions per boe of production) of the upstream oil and gas sector’s emissions has fallen, thanks to reduced flaring, better methane leak detection and mitigation, electrification and carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS). However, more work is needed on the absolute level of upstream emissions.

Wood Mackenzie’s unique asset-level emissions data allows us to track improvements and decarbonisation trends across the industry using a globally consistent methodology. In a recent examination of upstream scope 1 and 2 emissions, we asked whether the industry was delivering on decarbonisation. Fill in the form for a complimentary selection of slides from the report and read on for an outline of our conclusions.

Increasing demand offsets the sectors’ decarbonisation efforts

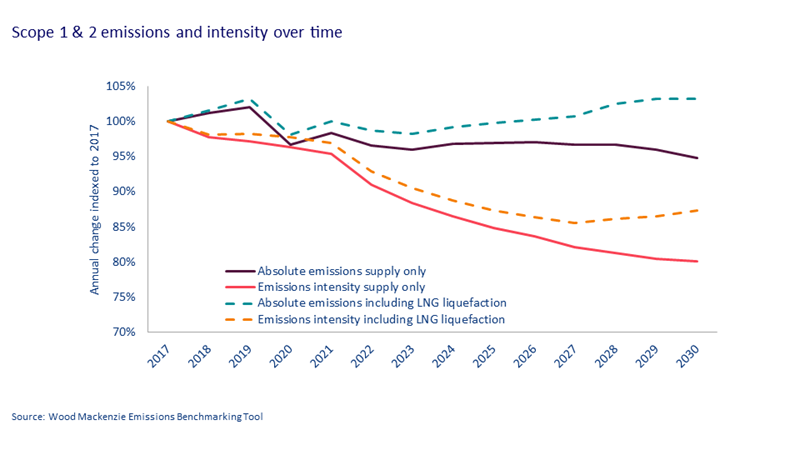

While emissions per barrel have fallen 12% since 2017, a post-pandemic rise in production to meet demand has caused absolute emissions to plateau, and 2024 could see a renewed year-on-year rise.

Upstream emissions remain closely linked to production, with the world’s largest oil and gas fields often the world's largest emitters. Fuel use in production and processing remains the largest source of emissions and the hardest to abate. Higher production volumes could push absolute emissions past pre-pandemic levels by 2028.

This is likely to be exacerbated by a rise in emissions from liquified natural gas, the linchpin of many companies’ energy transition plans and one of the fastest growing sectors. Including liquefaction emissions, LNG expansion could well push absolute emissions even higher.

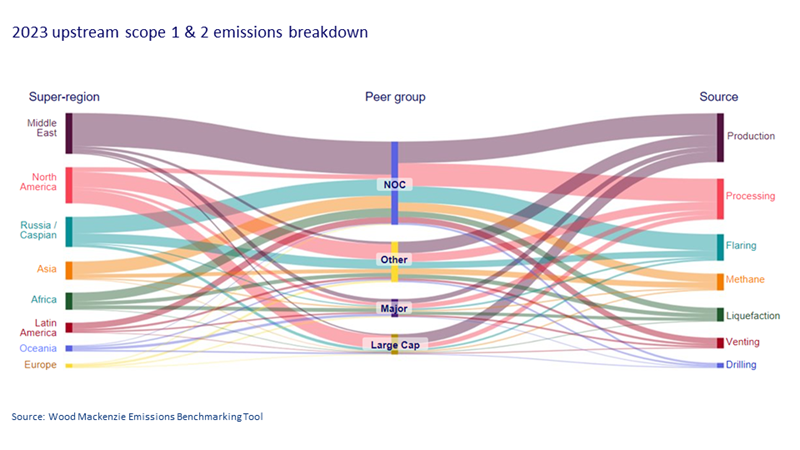

The largest oil and gas-producing companies and regions remain the biggest emitters. The Majors and Large Caps face the most scrutiny and pressure to decarbonise, amid increasing regulation and the introduction of carbon taxes, but are responsible for less than a quarter of total emissions. The remainder are attributable to National oil companies (NOCs), other independents, smaller international oil companies (IOCs) and private operators. Action on decarbonisation from the largest of these could really move the needle.

Sending up flares

Decarbonisation initiatives have to-date been most focused on flaring, methane and venting. But combustion-related emissions from production, processing, drilling and liquefaction account for two-thirds of total emissions. These sources are much harder to abate but fuel efficiency and electrification offer the best solutions.

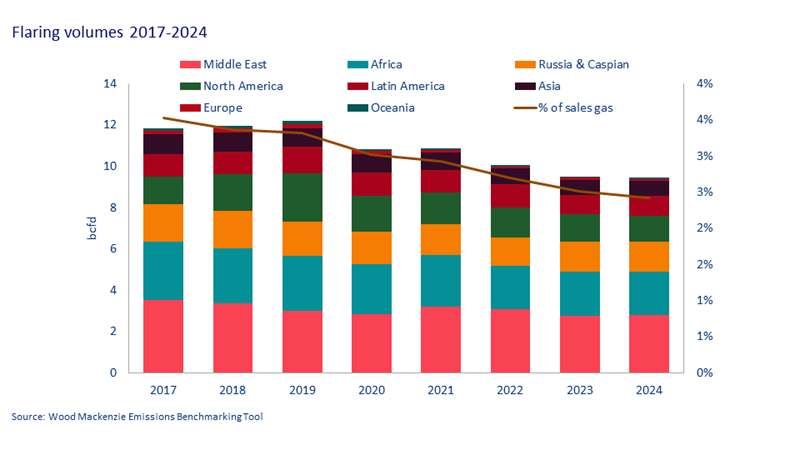

Flaring, the most visible of the sector’s emissions categories, has been cut most, driven by IOCs with global operations, and those keen to monetise the gas that was until recently considered an oil by-product. Regions with the tightest regulations and the largest IOC presence have seen the biggest cuts.

Flaring has often been tolerated in return for maximising oil production, but that is changing as countries like Iraq and Iran expand their domestic gas capacity to meet growing gas demand. Half of the top 20 flaring countries have endorsed the World Bank Zero Routine Flaring Initiative, obliging them to dramatically reduce flaring by 2030.

But more than 10 bcfd – a theoretical US$12 billion in revenue – is still burned yearly. Attempts to tackle flaring are being hampered by a lack of investment in gas infrastructure, processing capacity or local markets.

What are the solutions?

Local regulations are becoming increasingly supportive of decarbonisation and remain one of the most effective catalysts of emission reductions. The biggest driver of reductions in mature regions is falling oil and gas output, but Europe and Asia are also making progress on electrification and CCUS. Licensing bans and exploration restrictions in several countries, including in Europe and Oceania, will also have a long-term impact on upstream emissions.

CCUS can effectively tackle venting from high-CO2 gas fields but remains far too costly for large-scale combustion-related emissions abatement. Action on methane is a priority for the industry and could deliver rapid reductions, but measurement is difficult, and volumes are inconsistently reported. LNG expansion has offset flaring gains in North America, Oceania and Russia, but the US government focus on methane shows what can be achieved despite rising production.

Companies and governments need to try harder

Efforts need to move beyond the low-hanging fruit. Many companies and governments are only starting to set targets and develop decarbonisation strategies – they have some catching up to do. Carbon offsets and credits will play a major role in meeting net zero targets.

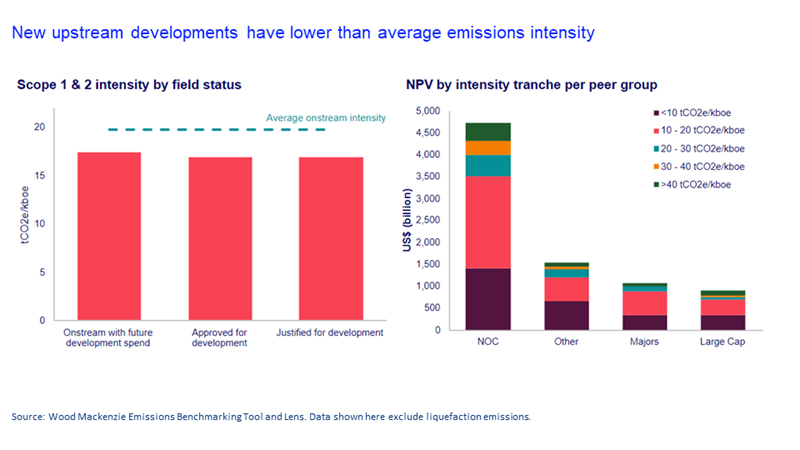

Investment is weighted towards cleaner advantaged barrels that will help to further reduce intensity, but ultimately progress on decarbonisation will depend on support from governments and regulators. As our Lens chart shows, the majority of future upstream spending is on below-average-intensity assets. New assets can be designed with emissions reductions built in and new facilities are cleaner and more efficient.

A third of spending will still go on above-average-intensity assets, predominantly brownfield spending on existing fields. Each dollar of investment on these assets will act to raise companies' emissions profile.