Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Europe looks for alternatives to Russian energy

In the short term, European customers are reliant on Russian oil, gas and coal. Governments are looking for ways to reduce that dependence over the medium and long term

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

Inside the ‘crazy grid’

-

Opinion

The Big Beautiful Bill is close to passing

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

-

Opinion

What the US attack on Iran’s nuclear installations means for energy

As fighting raged across Ukraine over the weekend, western countries moved quickly to disrupt Russia’s links to the global economy. In the short term the implications for energy have been minimal. The financial sanctions introduced in recent days have generally been specifically designed with exemptions for the energy trade, to avoid interrupting the flow of oil, gas and coal from Russia. In the medium and longer term, as Wood Mackenzie’s chief analyst Simon Flowers suggested last week, Russia’s conflict with Ukraine could cause a fundamental shift in its energy trading relationships with the rest of the world, and particularly with western Europe. Signs of that realignment are already starting to emerge. A long-term shift away from reliance on Russian energy and towards other sources — including LNG, renewables and nuclear power — has been signaled by European leaders.

On Saturday, the leaders of the US, EU, UK, Canada, France, Germany and Italy announced a package of financial sanctions intended to “further isolate Russia from the international financial system and our economies.” The measures include excluding some Russian banks from the SWIFT messaging system used for international payments, and restrict the Russian Central Bank’s use of its international reserves. The announcement had an immediate impact on the Russian rouble, which fell sharply in early trading on Monday morning.

The immediate impact on oil and gas sales, however, will be muted. Media reports clarified that the sanctions were not intended to stop Russia’s energy exports. As the Financial Times explained, the new sanctions “will either carve out certain energy-focused banks or use product definitions in the SWIFT system to permit energy-related transactions”.

As the world’s second-largest producer of natural gas, and one of the big three producers of crude oil, along with the US and Saudi Arabia, Russia plays a critical role in global energy supplies. Wood Mackenzie analysts warned last week that if the EU were to impose sanctions that stopped Russian gas flows immediately, it could by next winter result in shortages, factory closures, rising prices and ultimately a global recession.

Jen Psaki, President Joe Biden’s press secretary, said in a television interview on Sunday that energy sanctions were still “on the table” for the US and other countries, but highlighted the dilemma they faced. “We want to take every step to maximise the impact and the consequences on President Putin, while minimising the impact on the American people and the global community,” she said.

However, there have been several signs on recent days of western governments aiming to take steps that would over time reduce their reliance on energy imports from Russia. Olaf Scholz, Germany’s chancellor, told a special session of the Bundestag on Sunday morning that his government would accelerate the construction of two new LNG import terminals and add to Germany’s gas reserves in storage.

Germany shut down three nuclear power plants last week, and its last three are scheduled to close at the end of the year. There is now widespread agreement that it is too late to try to keep them open. Chancellor Scholz’s SPD-led government has supported the nuclear exit, and wants “ideally” to close Germany’s coal-fired power plants by 2030. It has acknowledged that an increased reliance on gas is likely to be a consequence. But it is now seeking to diversify the sources of that gas. The decision to delay certification of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia, which the German government had previously supported, was a stark illustration of how the landscape has changed. “We will do more to ensure secure energy supply for our country,” Scholz told the Bundestag. “We must change course to overcome our dependence on imports from individual energy suppliers.”

In France, meanwhile, the government is betting on nuclear power as a way to enhance energy security while cutting emissions. President Emmanuel Macron earlier this month announced the “rebirth” of the country’s nuclear industry, with up to 14 new reactors planned by 2050.

Liz Truss, the UK foreign secretary, has floated the idea of setting ceilings “over time” for how much oil and gas the G7 economies import from Russia.

In another sign of energy links between Russia and the west being loosened, BP announced on Sunday that it would exit its 19.75% shareholding in Rosneft. Both BP-nominated directors on the Rosneft board, Bernard Looney and Bob Dudley, resigned with immediate effect. The decision means BP will take two non-cash charges in its first quarter earnings: one for the difference between the assessed fair value of the Rosneft stake and its carrying value of $14 billion, and another of $11 billion mostly for accumulated foreign exchange losses.

Helge Lund, BP’s chairman, said in a statement that the company had operated in Russia with “brilliant” colleagues for 30 years, but the conflict in Ukraine “represents a fundamental change”. He added: “It has led the BP board to conclude, after a thorough process, that our involvement with Rosneft, a state-owned enterprise, simply cannot continue.”

Russia has been a reliable supplier of energy to western Europe and the world for many decades, through the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the presidency of Vladimir Putin. That record of reliability, plus its abundant hydrocarbon resources, are the reasons that Russia plays such an important role in international energy markets. Finding alternatives will be neither quick nor easy. But western governments are at least thinking seriously about how it could be done.

An expanded role for US LNG

For European countries wanting alternatives to Russian gas, the US is an obvious place to find suppliers. The US has the gas resources, the infrastructure, and the construction capabilities to achieve a significant increase in LNG exports relatively quickly. It cannot be an answer to any immediate shortages — US LNG export facilities are already running at full capacity — but in a few years’ time it could make a significant contribution to reducing Europe’s dependence on Russian gas.

Proposed new US LNG projects with a total capacity of about 160 million tons per year (mmtpa) have permits for construction and export sales. That is more than the total US export capacity currently in operation and under construction, which totals about 110 mmtpa. European countries’ hunt for additional supplies increases the likelihood of those projects going ahead.

Venture Global’s newly completed Calcasieu Pass project in Louisiana has set the pace in terms of how quickly new export capacity can be brought on stream. The final investment decision for the plant was taken in August 2019, and it is scheduled to ship its first cargo any day now, just 30 months later. “What Venture Global is doing is showing that it doesn’t have to take a long time to bring new US export capacity on stream,” says Alex Munton, Wood Mackenzie’s principal analyst for Americas LNG. “They have used modular construction, which means a lot of the work can be done off-site, in factory conditions. And their contracting strategy, doing their own procurement, has helped hold costs down.”

There are six new US LNG projects that have all the permits they need to start construction. The nearest to final investment decisions are Cheniere’s Corpus Christi Stage 3 project and Venture Global’s Plaquemines LNG. We expect both to start construction this year. Others such as Tellurian’s Driftwood LNG and NextDecade’s Rio Grande LNG have also have signed EPC contracts. All of these projects have also signed sales contracts with buyers including Shell, Vitol and Gunvor.

Behind them there are six more proposed projects along the Gulf of Mexico coast that have approval from the Department of Energy for LNG exports without restrictions on destination. Given the increased level of interest from European buyers, we expect at least two or three new US export projects to secure the financing they need and take FID this year, with more following in future years.

“Before, European customers were not very enthusiastic about signing long-term contracts to buy LNG. There were questions over whether they would still be selling gas in 20 years’ time, given Europe’s net zero goals. And US contracts locked them into these fixed long-term commitments,” says Wood Mackenzie’s Munton. “Things are completely changed now. The conversations with customers will be very different.”

After Germany announced it was putting the certification of Nord Stream 2 on hold, Dmitry Medvedev, former president of Russia and now deputy chair of the Security Council, tweeted: “Welcome to the brave new world where Europeans are very soon going to pay €2.000 for 1.000 cubic meters of natural gas!” That is a price equivalent to about $62 per million British Thermal Units (mmBTU).

That might be an exaggeration: European benchmark TTF gas futures for December 2022 were trading at the equivalent of about $30 /mmBTU at the end of last week. But even so, US gas priced at about $4.50 / mmBTU for front month benchmark Henry Hub futures, giving a delivered cost of LNG to Europe of about $9-$10 / mmBTU, still looks highly competitive.

One potential hitch in the expansion of US LNG exports is a move by federal regulators to look more closely at greenhouse gas emissions when deciding whether a proposed project is in the public interest. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission earlier this month issued an interim policy statement for approvals of new pipelines and LNG plants. Any project with greenhouse gas emissions of more than 100,000 tons per year of carbon dioxide equivalent will be required to submit an Environmental Impact Statement including an assessment of its climate impact, which will then be taken into account in FERC’s decision on whether to approve the project.

The policy statement, which accompanied a wider clarification and expansion of the certification process for new gas pipelines and LNG facilities, follows a ruling last year from the DC Circuit court of appeals that FERC had failed to properly address climate impacts and local pollution when approving two LNG export plants in Texas.

In a dissenting comment, Commissioner James Danly, who opposed the new policy, argued that it represented “a dramatic expansion” of FERC’s authority to impose conditions, and was probably not supported by the law.

The new policy applies to pipelines only if they cross state lines, and most of the key routes for supplying LNG plants on the Gulf coast will be within either Texas or Louisiana, so any new infrastructure needed there is unlikely to be affected. And as discussed above, there is still room for a significant increase in US LNG exports just from projects that already have FERC approval. So the new policy may not have much immediate impact on the LNG outlook. However, it will create additional challenges for developers in future. For the Biden administration, it is a sharp demonstration of how its climate goals and strategic objectives can conflict.

Record-breaking bids for US offshore wind

An auction of offshore wind leases off the coast of New York and New Jersey attracted a record $4.37 billion in high bids, in the latest sign of strong international interest in the US market. The auction round, run by the federal government, shattered the previous record of $405 million, achieved at the previous US offshore wind auction in 2018.

Success in the auction means RWE Renewables of Germany is entering the US offshore wind market for the first time, as part of the Bight Wind joint venture. Shell also said it had provisionally won a lease block, through its joint venture with EDF of France.

Søren Lassen, Wood Mackenzie’s head of offshore wind research, said that the level of bidding “tells us that that the appetite for offshore wind continues to soar, not just in the US but globally.” He added that the auction was important for the Biden administration to stay on track for its goal of having 30 gigawatts of offshore wind generation installed by 2030. “The sheer GW capacity of these leases drives a much-needed expansion of the US offshore wind pipeline by 30%,” he said.

We will have more details of the auction and its implications for the industry later in the week

The US Postal Service rejects electric vehicles

The US Postal Service is pressing ahead with buying predominantly gasoline-fueled vehicles for its new generation of delivery vans, despite a sustained attempt by the Biden administration to persuade it to buy electric.

Quotes of the week

“To be clear, our sanctions are not designed to cause any disruption to the current flow of energy from Russia to the world.” — Daleep Singh, US Deputy National Security Adviser

“This latest military escalation also shakes the economic cooperation between Russia and Europe that has been built up over decades. That will have far-reaching consequences. To what extent cannot yet be foreseen.” — Mario Mehren, Chief Executive Officer of Wintershall Dea

“We are doubling down on renewables. This will increase Europe’s strategic independence on energy.” — Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission

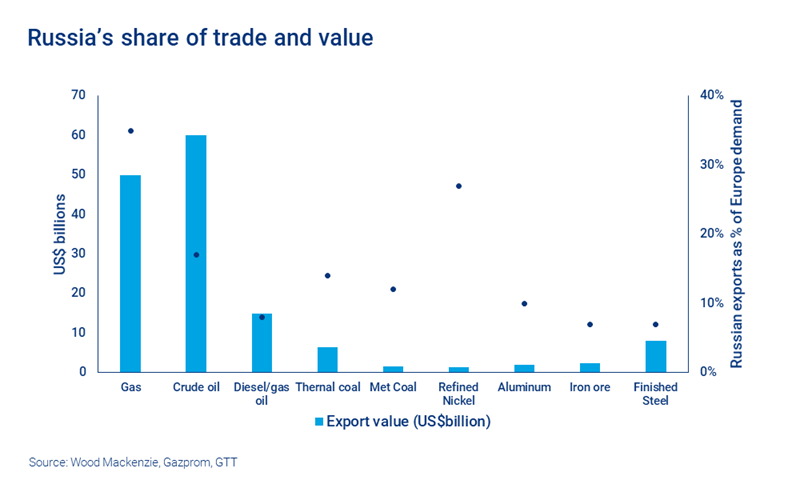

Chart of the week

This comes from Wood Mackenzie’s Insight report last week on what the conflict in Ukraine means for global commodities. It shows the value of Russian exports, and Russia’s market share in Europe, for a variety of commodities. What is particularly noteworthy is that although oil and gas are the biggest export earners, and it is in gas that Russia’s share of the European market is highest, there are many other sectors where Russian production is highly significant for the west, including nickel and coal.