The domino effect of the Ukraine crisis on gas and LNG

Weighing up the risks of cuts to Russian gas exports

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

The threat of military escalation in Ukraine is ramping up the pressure in Europe’s gas market. The chances of Russia intentionally cutting its exports are remote. But any disruption to pipeline volumes could lead to energy chaos in Europe and ripple out into global gas and power markets. How it might all play out is complicated. I turned to our gas experts, Massimo Di Odoardo, Kateryna Filippenko and Penny Leake to guide me.

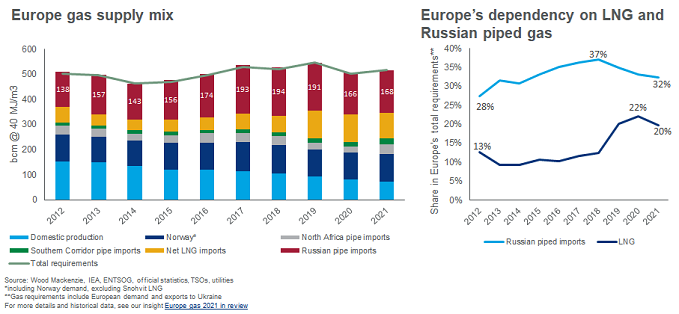

How dependent is Europe on Russia gas?

Russia supplied 168 Bcm to Europe in 2021, down from 191 Bcm in 2019 but still meeting around one-third of demand. Volumes reaching Europe transiting via Ukraine have halved since 2019 but are still 40 Bcm a year – around 8% of total demand. Nord Stream 2, the final step in Russia’s plan to grow its exports to Europe whilst circumventing Ukraine, still awaits final approval from the EU. Germany is the biggest buyer of Russian gas (40 Bcm) but Italy, Austria and Slovakia are most dependent on Ukraine transit gas.

Has LNG become more important?

Yes, imports have doubled over the last few years and contributed 20% to Europe’s supply in 2021. Global LNG capacity is finite until new projects come on stream in a few years, but it’s flexible supply which can move to where demand is. LNG volumes into Europe surged through Q4 to hit record levels in January. Warmer temperatures in Asia prompted LNG traders to reroute cargoes to take advantage of higher prices in Europe, temporarily reducing European buyers’ requirements of Russian imports. That though has now reversed with the arrival of cold weather lifting Asian spot LNG prices.

Does Europe need higher volumes of Russian gas this year?

Yes, we expect Russian pipeline imports to increase by 20% above the January lows for the next few months consistent with the capacity booked at the end of 2021. The higher volumes are needed not just to get through this winter but to prepare for next. Inventories are already well below the 5-year average and will be well under half the ‘normal’ seasonal low point in March.

Even if Russian pipeline gas continues to flow through spring and summer, winter 2022/23 will begin much as this one did – with inventories at a record low. That’s assuming no more Russian gas is made available for export either through Nord Stream 2 or the other routes.

Were all gas flows to stop today, existing gas storage would run out in 6 weeks.

Can Europe cope without Russian gas?

No, we don’t think European governments could countenance blocking Russian imports even if there’s full-scale conflict in Ukraine. It would prove impossible to find alternative volumes to meet 28% of annual demand. Were all gas flows to stop today, existing gas storage would run out in 6 weeks; demand destruction would be massive; and if disruption was prolonged, gas inventory couldn’t be rebuilt through the summer.

We’d be facing a catastrophic situation of close to zero gas in storage for next winter. This scenario highlights how dependent Europe has become on Russian gas and the critical role diplomacy and commercial sensibilities have to play to ensure supplies keep flowing.

What if transit volumes through Ukraine are disrupted?

That could happen as an unintended consequence in the event of conflict. Losing those volumes might be more manageable, particularly through the summer when demand is lower; and if Russia was willing to re-route gas to utilise spare capacity in the pipeline from Belarus to Poland.

But even with the Belarus option, Europe would have to pull every lever in the energy system to keep the lights on – reducing gas burn and cranking up mothballed nuclear and coal plant (with all the backlash around higher emissions that would bring); maximising indigenous gas production (Norway, Netherlands) and pipeline imports (Algeria, Azerbaijan); and persuading Asian buyers to switch to coal and free up LNG. But it would only be a temporary solution to muddle through the summer and would leave Europe with perilously low storage volumes going into winter 2022/23.

Are high prices a problem for this year only?

That depends. A defusing of military tension would quickly lead to lower prices as the winter ends, though it’s hard to imagine the market can go back to pre-crisis levels with no risk premium after everything that’s happened. Any other scenario and the initial reaction would see prices through the roof. The likelihood is that Europe faces elevated prices compared with a year ago for some years until new supply, mainly from Qatar and US, becomes available in the middle of the decade.

What are the implications for the global gas market?

First, Russia’s apparently strong position with its Europe customers is not quite what it seems. Russia also has a lot to lose – not least its reputation as a reliable supplier of gas; and Nord Stream 2 which is in danger of becoming a white elephant. Should Europe choose to wean itself off Russian gas it’s a bullish signal to LNG developers in the US, Qatar and beyond.

Second, there’s the impact of soaring prices and supply uncertainty on gas demand, in Europe and elsewhere. Europe might use the crisis to push even harder on its plans for net zero. Growth in the global market longer term is all about Asia, with gas displacing coal to meet rising energy demand and reduce emissions. High prices and volatility do the cause no good at all.