Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Nuclear power needs a way to break the stalemate

Political support is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a revival in investment in new reactors in the US

10 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

-

Opinion

What the US attack on Iran’s nuclear installations means for energy

-

Opinion

How do we adapt to a warming world?

-

Opinion

What the conflict between Israel and Iran means for energy

US politics today, both in Congress and among voters, are more polarised than they have been for decades. Policies with strong bipartisan support are rare. So it was a noteworthy moment last week when the Senate voted by an overwhelming 88-2 majority to pass legislation to support the deployment of advanced nuclear power.

The vote was an indication of how nuclear power is now widely supported across the political spectrum in the US. The politics of energy and climate are, in general, sharply polarised between the two main parties. Just seven months from now, the country could have a new administration that would take a very different view from President Joe Biden on the need to incentivise investment in wind and solar power. A key advantage for nuclear power is that policy support is likely to be resilient through successive revolutions of the political cycle.

Yet while stable long-term policy support may be a necessary condition for a revival of investment in nuclear power in the US, it is not sufficient. Investment is stagnating because the commercial case has not been strong enough. For nuclear power to begin to grow again in the US, that will have to change.

The legislation passed in the Senate last week, the Accelerating Deployment of Versatile, Advanced Nuclear for Clean Energy (ADVANCE) Act, includes a series of measures intended to expedite the licensing and construction of a new generation of reactors. It aims to cut costs for developers by, among other things, mandating the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to make its regulatory reviews “efficient, timely, and predictable” and to streamline its processes for environmental approvals.

The act also requires the NRC to develop a pathway to expedite licensing for new nuclear facilities at brownfield sites where there have already been other reactors or fossil fuel power plants. As a sign of all these changes, the NRC is being required to update its mission statement to endorse the beneficial use of nuclear material and energy.

This activity in Congress fits closely with moves being made by the Biden administration. The Department of Energy last week issued a notice of intent to provide up to US$900 million to support the deployment of new small modular reactors (SMRs) in the US. Jennifer Granholm, the energy secretary, said the administration aimed to “reassert American leadership in this critical energy industry”.

A key reason for the broad-based support for nuclear power is that it aligns climate, economic and national security objectives for the US. The Biden administration has been emphasising the climate benefits. The Department of Energy says that to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, the US will need between 700 to 900 gigawatts of “clean firm” generation capacity, meaning dispatchable zero-carbon power. Nuclear would have to play a key role in that.

But even if emissions were not an issue, there would still be a case for the US government to support nuclear development. The US Export-Import Bank has identified SMRs as a potentially substantial international market, but American companies will find it difficult to compete if they cannot demonstrate successful deployment in their own country.

Nuclear technology is also an important factor in international diplomacy. The refusal of multilateral development banks to support nuclear projects has left space for Russia and China to expand their global influence.

The big problem for nuclear power in the US is that it is very hard to make the economics work. The last two new reactors to be built in the US, Units 3 and 4 at the Vogtle plant in Georgia, have come into service seven years behind schedule and with a cost overrun of more than 100%. The levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) from the new reactors has been estimated at about US$180 per megawatt hour, which is getting on for three times the cost of power from a new combined-cycle gas turbine plant (CCGT).

That experience has left other companies sceptical about new nuclear construction. Chris Womack, chief executive of Southern Company, parent company of the Vogtle plant operator, said recently he expected more commitments to build new reactors in the US before 2030. But no projects have yet been announced.

What would have been the country’s next new nuclear plant, the Carbon Free Power Project in Idaho, using NuScale SMRs, was cancelled last year after failing to find enough buyers for its power. The target LCOE for the plant was estimated at US$89 / MWh, after tax credits and federal government support, and there were clear risks that it could rise higher. With US LCOEs averaging about US$70/MWh for new gas-fired plants, US$50/MWh for onshore wind and US$31/MWh for utility-scale solar, again including tax credits, it was hard for local utilities to make the case that they should sign their ratepayers up for higher costs and higher financial risks.

If ordinary ratepayers cannot be asked to bear the costs of new nuclear deployment, there are other customers that could be prepared to pay: large commercial users and, in particular, the big tech companies. Rapid advances in artificial intelligence mean that demand for data centre capacity is booming, as is demand for electricity to power those facilities.

Tech companies hoping to earn vast revenues from the new generation of AI applications are much less price-sensitive buyers than households and small businesses. Most of them also have demanding goals for cutting emissions and using low-carbon electricity. Given that data centres typically need 24/7 power, wind and solar cannot be a complete solution, and tech companies have a keen interest in those “clean firm” technologies, including geothermal, long-duration storage and hydrogen as well as nuclear.

The problem is not so much money, but time. “Time to power” is a vital consideration for companies racing to offer the most advanced new AI applications. New nuclear plants that have long licensing and construction timetables, and run the risk of falling many years behind schedule, are not the most attractive option from that point of view.

The only deal yet announced for a tech company to use nuclear power for a data centre involves an existing plant, which came on line in 1983.

Tech companies and others with facilities that create large loads on the grid are certainly interested in new nuclear. The alliance formed by Google, Microsoft and Nucor to use their buying power to accelerate the deployment of advanced energy technologies is looking at nuclear among other options. But that initiative could have a material impact on US generation capacity in the 2030s and beyond – not in the possibly hectic period of growth in AI that some expect over the next few years.

Not everything in nuclear deployment in the US is stagnating. TerraPower, the advanced nuclear startup founded by Bill Gates, broke ground on its first project in Wyoming earlier this month. However, only its non-nuclear construction can begin because the NRC has not yet given its approval.

The Terrapower project is a first-of-a-kind development for its Natrium reactor technology, intended to validate its design, construction and operation. Construction is scheduled to take five years, so even if all goes well, it is likely to be well into the 2030s before wider commercial deployment is underway.

In light of all these issues, the next new reactor project to proceed in the US could be another Westinghouse AP1000, of the kind built at Vogtle, not an SMR.

A Department of Energy report last year on advanced nuclear deployment argued that most of the root causes of the delays and cost overruns at Vogtle were within the control of the project’s leadership, including incomplete design and inadequate quality assurance. Learning the lessons from that experience should mean that many of those mistakes can be avoided.

Jigar Shah, director of the energy department’s Loan Programs Office, which provided financing guarantees for the Vogtle project, has said that the cost of Unit 4 was already 30% less than for Unit 3, as the project teams had been trained and learned from their experience on the first unit.

In the improbable event that cost declines continued at that rate, by Unit 10 the LCOE would be in line with utility-scale solar. But even if that projection is unrealistic, the learning from Vogtle could be useful for other new nuclear plants being built in the US.

The danger is that the longer the country goes without another new nuclear project, the more that pool of expertise and supply chain capability will evaporate, and the benefit will be lost. That threat argues for decisive action to get nuclear construction underway again in the US.

As the Department of Energy report noted last year, “to progress beyond this stalemate, deliberate action to kickstart and sustain the nuclear industry is necessary”. That means creating demand, and possibly additional financial support from the public sector. Without that, all the warm feelings about nuclear power in Washington will amount to very little in terms of concrete and steel in the ground.

In brief

The Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) is close to a deal to buy German chemicals company Covestro for about €14.4 billion. Covestro’s chief executive Markus Steilemann said the company had been making good progress in its discussions with ADNOC.

Ukraine is continuing its campaign of drone strikes against Russian oil infrastructure, hitting three refineries on Thursday night.

The second-best selling electric vehicle in the US, after a Tesla, is a Lectric electric bike.

Other views

A window opens for OPEC+ oil – Simon Flowers and Ann-Louise Hittle

The state of the US energy storage market – Allison Weis

The state of US distributed solar-plus-storage – Max Issokson

What’s in store for gas and LNG in Europe? – Lucy Cullen

Can the EU and US hit EV targets amid supply chain shake up? – Max Reid

More running room in Lower 48 efficiencies? – Maria Peacock and Josh Dixon

Europe faces an unusual problem: ultra-cheap energy – The Economist

How companies are starting to back away from green targets – Kenza Bryan and Attracta Mooney

Batteries as a military enabler – Joseph Webster

Maybe don’t spray-paint Stonehenge – Tyler Austin Harper

Quote of the week

“It’s obviously uncomfortable, and it’s unfortunate, I don’t know anybody who’s involved in this campaign who was happy that literary festivals are suffering for funding… The goal was to get Baillie Gifford to divest; it was not to get the festivals to lose their sponsors.”

The author Naomi Klein explained that the Fossil Free Books campaign had not had its intended impact. Last month, the campaign called on the UK fund manager Baillie Gifford, sponsor of 10 literary festivals including Hay, Cheltenham, Edinburgh and Stratford, to “divest from the fossil fuel industry and from companies that profit from Israeli apartheid, occupation and genocide”. Baillie Gifford has roughly 1%-2% of its assets under management invested in fossil fuels.

In response to the campaign, the Hay Festival decided to end its sponsorship by Baillie Gifford, which then also cut its ties with the other festivals.

Chart of the week

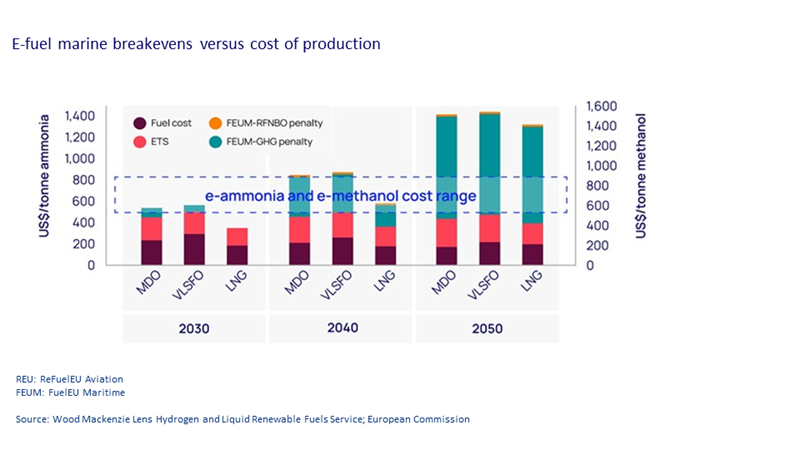

This comes from our new Horizons report: ‘Adding fire to e-fuels: Are synthetic fuels the key to unlocking growth in hydrogen?’ It shows cost comparisons for three options for marine fuels – marine diesel oil (MDO), very low sulphur fuel oil (VLSFO) and LNG – set against possible ranges for the synthetic fuels e-ammonia and e-methane.

Three points are worth noting. Firstly, the cost of the fuel itself, shown in the purple bars, looks likely to be significantly lower than the cost of e-fuels, even in 2050. Secondly, even adding in the cost of carbon under the EU’s Emissions Trading System, e-fuels are still significantly more expensive. Thirdly, however, it looks as though the impacts of the 2023 FuelEU Maritime Regulation, shown by the blue-green bars, will make e-fuels competitive against their conventional alternatives. Often by 2050, sometimes by 2040, and perhaps in some occasional cases even by 2030.

Get The Inside Track

Ed Crooks’ Energy Pulse is featured in our weekly newsletter, The Inside Track, alongside more news and views from our global energy and natural resources experts.