Competing for capital in a downcycle

Upstream spend plummets to a 15-year low

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

Back to work, back to planning. Many IOCs and NOCs over the next month will put the final touches to 2021 budgets and finesse the rolling five-year strategic plan. An immediate priority is to reset spend after a steep fall in the oil price. But the economic fallout of Covid-19 and the gathering pace of the energy transition make decisions on capital allocation in this downturn that bit more challenging. Tom Ellacott, Head of Corporate Analysis, and Fraser McKay, Head of Upstream, identify three main factors affecting decisions on investment in upstream, still the biggest slice of the corporate pie.

First, capital is scarce – industry finances have been hit very hard these past six months. The sector still needs over US$40/bbl on average to break even on cash flow, even after the cost and spend cuts already announced. Around half of the 50 companies we cover are cash flow negative in 2020 and 2021 at today’s oil price.

Balance sheets have been weakened by US$160 billion of write-downs through Q2 2020. The seven Majors alone wrote off US$57 billion of assets, pushing leverage to 30% on average (including operating leases). That’s the highest since Q2 2006, and at the upper end of the 20% to 30% most consider as ‘comfortable’. Only Chevron’s leverage at 17% is below.

Deleveraging will be a priority for higher-leveraged players; a pick-up in a moribund M&A market will see many companies selling assets to raise cash.

Second, the need to appease capital markets. All companies have tightened criteria for new investment, including higher hurdle rates and lower oil price assumptions; and many now factor in higher carbon prices than before the crisis. Fewer projects will proceed and spend will be lower.

Already hostile to growth strategies prior to the crisis, investors now wield even more influence. US Independents, pilloried for outspending cash flow to pursue growth in the boom years of tight oil, have finally kowtowed. Some are adopting a capital discipline framework that restricts investment to 70% to 80% of operating cash flow, with surplus cash flow returned to shareholders.

Tight finances come at an awkward time for those companies with aggressive decarbonisation strategies.

Third, the energy transition has moved up the agenda. Tight finances come at an awkward time for those companies with aggressive decarbonisation strategies. The Euro Majors other than Total have already cut dividends to reflect what is the beginning of a momentous shift in capital allocation. These companies aim to channel 5% to 15% of organic investment into zero-carbon assets. That’s up to US$3 billion annually in the next few years for Shell and Equinor, while Eni has nearly a quarter of capex earmarked for renewables in 2023.

None will want to be seen to scrimp on scaling up new energy, a flagship strategy. But near-term funding will be challenging with balance sheets stretched and legacy upstream and downstream cash flow depressed. It may be a case of robbing Peter to pay Paul, with other hopeful recipients of what little capital is available – exploration for example – the losers.

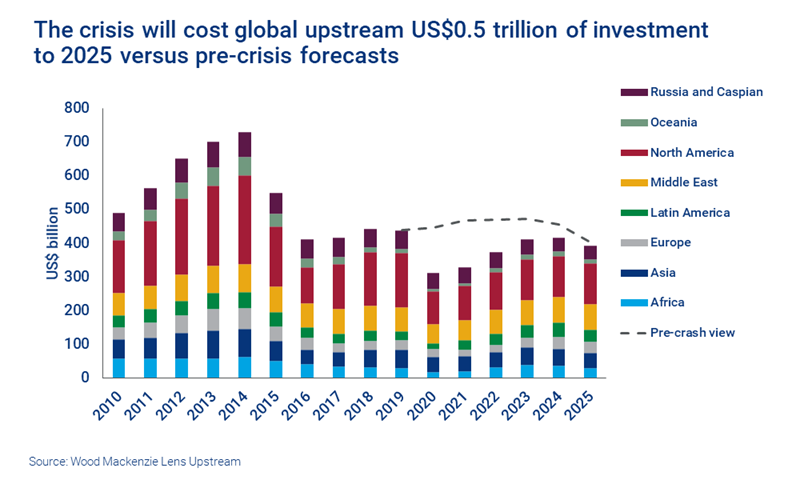

What does this all mean for upstream investment? Spend in 2020 will be the lowest in 15 years. Our forecast is US$310 billion this year, 30% down on 2019 and 60% below the 2014 peak of US$730 billion. Adjusted for the higher spend in Q1 pre-crisis, the present run-rate is well under US$300 billion.

Upstream will be in a spending trough through 2021, quite likely beyond. Greenfield conventional project FIDs have virtually dried up. We expect around 10 project FIDs over 50 million boe this year, down from 40 in 2019 and 50 the year before. Tight oil spend is down over 50% in 2020. A pick-up in conventional spend likely awaits Brent recovering above US$55/bbl and confidence that it will stay there; US tight oil needs WTI over US$50/bbl.

And what does it mean for the oil market? An extended lull in investment in liquids supply today will help rebalance the current oversupplied market. But if demand recovers back to 100 million b/d as we expect over the next two or three years, the market will tighten.

Our Macro Oils team reckon the 2020 crisis will prove to have a more lasting effect on oil supply than demand. They forecast demand in 2025 will be 1-2 million b/d lower than our pre-crisis forecasts but liquids supply will be 4 million b/d lower. That points to firmer prices in the middle of the decade – an outcome that would reward companies that are able to invest through the downturn.

We’ll explore the theme of underinvestment in oil and gas supply in our 2020 Energy Summit EMEA taking place on 6-8 October 2020.