Interested in learning more about our oil & gas solutions?

Decarbonising crude

How upstream carbon emissions can ripple through the oil value chain

4 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

Crude oil’s centrality to the global economy has been reinforced in the energy crisis of 2022. Oil demand has recovered strongly from the Covid-induced dip and, despite an economic slowdown, could reach record highs next year. But COP27, underway in Egypt, is a reminder that oil consumption must fall if the world is to achieve net zero. In our accelerated energy transition 1.5 °C scenario, demand falls by two-thirds from 100 million b/d today to 35 million b/d in 2050.

In the meantime, pressure on the upstream and refining sectors to decarbonise the crude oil value chain is mounting. Alan Gelder and Sushant Gupta of our Refining team took me through their latest analysis.

What’s the decarbonisation challenge for oil?

The sector is responsible for one-third of global emissions. Around 70% of these are Scope 3, released into the atmosphere on combustion at the point of consumption, mainly in transportation, heating or industry. The other 30%, Scope 1& 2, are split almost evenly between upstream production and refining. Emissions have to start falling soon, and precipitously, if the world is to get onto a 1.5 °C pathway.

Why is crude’s carbon intensity in the spotlight now?

Decarbonisation of the crude oil value chain is gathering momentum. The price reporting agencies that record crude prices are considering including upstream carbon emissions in their methodology, paving the way for carbon taxes to influence buyers’ behaviour.

There is a broad range of carbon intensities across the numerous different crudes. Including the cost of carbon will change ‘traditional’ price differentials that today are determined mainly by the crude’s gravity (API) and sulphur content. For refiners, carbon intensity will not only change the economics of selecting crudes as feedstocks, but how they themselves tackle reducing emissions from refining.

How do you measure carbon intensity for crudes?

Our data assesses the carbon intensity from well to wheels globally, asset by asset, from upstream through refining and transportation. We can then benchmark crudes on relative price using our models and tools.

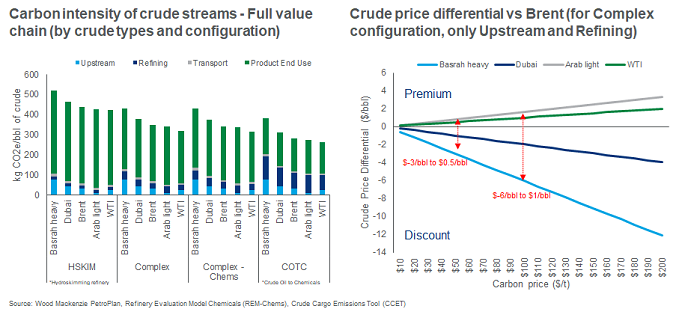

Most upstream emissions are produced by powering operations (70%); the rest comprise non-combustion emissions from methane losses, flaring gas and venting CO2. Upstream carbon intensity for crudes ranges from 10 tons to 70 tons of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) per 1000 bbls of crude produced. Arab Light is at the low end, Brent roughly in the middle and Basrah Heavy among the highest.

Refining emissions intensities are a similar order of magnitude, from 20 tons to 100 tons of CO2e per 1000 bbls of crude processed, the range a function of crude feedstock and the configuration of the refinery processing it. More complex refineries have higher processing capability to produce higher value products so tend to produce more emissions. Likewise, sites with deep integration with chemicals are more energy-intensive and produce higher emissions.

Product end-use emissions range from 250 to 450 tons of CO2e per 1000 bbls of crude. Refineries integrated with petrochemicals tend towards the lower end because plastics are not combusted on consumption.

How will including carbon emissions change crude pricing?

It will change the relative values of different crudes. Traditionally, crude price differentials reflect the difference in value of the yield of products the typical refiner achieves from processing alternate grades.

In Europe, refiners already pay a carbon price on a portion of emissions that arise from crude processing through the EU emissions trading scheme. As upstream carbon intensity becomes an independent, reported variable, the roll-out of carbon pricing in other fiscal regimes will lead to a widening of differentials between lower and higher emission-intensive crudes. The differentials will change with the level of carbon price.

We estimate that at US$100/ton of CO2, the Brent-Dubai differential could double to US$4/bbl (see chart), assuming the refiner pays all upstream and refinery processing emissions. Arab Light’s low upstream emissions are a significant advantage and its typical discount to Brent could be eliminated.

What are the implications for companies?

For crude producers, the introduction of carbon pricing will accelerate action to decarbonise upstream operations. Low carbon-intensity crudes will have a big advantage over higher carbon-intensity crudes, which will be sold at a bigger discount. By actively cutting emissions, producers of higher carbon-intensive crudes can close the gap to a degree, recapture ‘lost’ revenue and establish a more sustainable and marketable crude stream.

Refiners may have a short-term bonus from buying discounted, higher carbon-intensity crudes. However, their longer-term interest, too, is best served by delivering products with a lower carbon intensity. As carbon prices rise, refiners will increasingly look to buy lower carbon-intensity crudes and decarbonise their refining processes.

The elephant in the room is who bears responsibility for emissions from product end use. The vast majority of refinery sites have product end-use emissions that account for up to 90% of total oil value-chain emissions. Carbon charges for product end-use emissions could dwarf all other categories of value chain if borne solely by the refining sector.

In this scenario, refinery location – and the carbon policy it operates in – will be critical.