Future cost of new oil supply: shale vs conventional

Implications of tight oil’s hegemony

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

The seismic shift away from conventional producing regions to US tight oil over the last few years is now entrenched in the outlook for global supply. It’s a primary driver of corporate strategy for many IOCs. But there’s a risk it will lead to a weakening of critical skill sets and disrupt the established talent channels feeding into the industry.

The world needs another 23 million b/d of additional supply by 2027. This ‘supply gap’ opens up as demand grows by a cumulative 8 million b/d and as existing producing fields decline. Peak demand won’t happen in this timescale (though it may soon afterwards). It’s a lot of new oil production, around 25% of total supply today. A sizeable chunk will be sourced from improved recovery from existing fields and new discoveries according to the latest analysis from Harry Paton, of our Global Supply team.

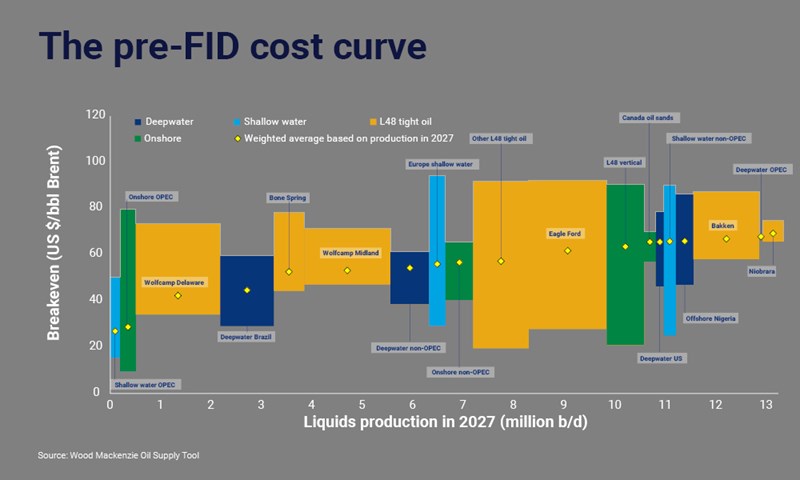

The bulk, over 13 million b/d, will come from pre-FID conventional projects and future drilling in the US Lower 48.

Harry Paton

Senior Research Analyst, Oil Supply

Harry is a member of four oil supply research team. His focus is developing oil price models and benchmarking assets.

Latest articles by Harry

View Harry Paton's full profileUS tight oil is winning the battle between the two. Having not figured at all in the equation early this decade, Lower 48 plays are forecast to deliver over 9 million b/d of new production by 2027 - 12% more than we expected a year ago.

There’s positive news for the conventional world too. Forecasts for supply volumes from green field projects halved after the oil price crash, as the high-cost developments of the boom times were deferred or scrapped. The current suite of pre-FID projects show improvement: NPV,15 Brent break evens averaging US$55/bbl, well down on the US$75/bbl peak three years ago. These projects will deliver a combined 4.6 million b/d by 2027, 0.6 million b/d more than we forecast a year ago.

H2 2017 data set Breakevens calculated point forward at NPV15, weighted average based on liquids production in 2027, blocks exclude upper 90% and lower 10% to exclude outliers.

Signs of the conventional sector recovering? Up to a point. The increase in future production is in the main from Brazil and Guyana where the giant, high-quality reservoirs have very low unit costs: NPV,15 weighted average break evens of US$48/bbl and US$40/bbl respectively pull the average down. Much of the rest of the conventional opportunity set is expensive and thin, with a few exceptions such as Norway and Senegal. More work still needs to be done to reduce costs and get project break evens in other geographies competitive with the best tight oil plays.

Not all future tight oil will be cheap and it won’t all be easy to extract.

Parent/child wells may limit drilling intensity and the focus of drilling will necessarily move into tougher rocks as sweet spots are drilled out. But this latest analysis confirms a trend that’s gained momentum through this decade. The axis of new supply to the oil market has swung decisively towards the US and it’s likely to stay that way for some years.

Two thoughts on tight oil’s hegemony. First, how it continues to shape corporate strategies.

Marathon’s sale of its Libyan assets to Total this month is just the latest of a series of disposals that all but ends decades of internationalisation – retrenching like so many of its US Independent peers to its Lower 48 core. Chevron’s latest plans are concentrated on its first rate Permian position, a big change after a period of heavy investment overseas.

Our cost curve analysis validates the increasing focus on the Lower 48 by IOCs. But tight oil will have its limits - the resource won’t last forever. Companies that lack portfolio diversity, internationally and across resource themes, and which allow attendant skill sets to wither away, may find themselves at a competitive disadvantage in time.

Second, there are profound implications for the industry’s next generation of engineers and geoscientists, already threatened by digitalisation and artificial intelligence.

Prospects look fine if you’re at school in Texas and on the cusp of a new career in US unconventionals. Thin pickings for graduates in much of the rest of the world. High rates of graduate placement into oil and gas companies from some of the best vocational courses are a thing of the past.