Stemming the tide of plastic waste

And how increased recycling will cut oil demand

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

We’ve all had our ‘Blue Planet’ plastic moments. My latest was on a remote Hebridean island in a rare heatwave last month, swimming on a pristine, deserted beach with only a basking shark for company. Pristine, save for the plastic ropes, twine, broken creels, bottles, containers, floats, nets, six-pack rings and indeterminate shapes of polystyrene littering the shoreline.

Alongside climate change, the rising tide of environmental waste, plastic included, is society’s other sustainability challenge. I asked Guy Bailey and his Petrochemicals Research team how we can get on top of the problem.

Why is plastic waste so out of control?

The litter on your beach is just one symptom of the explosive growth in consumption of materials in the last 50 years, fuelled by a rising population, growing incomes and new technology. People want to buy more and more stuff, much of it made of plastic or packaged in it. The majority of plastic today is single-use and once it’s served its purpose, it’s dumped in landfill or just discarded.

Will plastic consumption continue to grow?

Yes. Intensity of use is actually falling in richer service-based economies – in the US, plastic consumed per unit of GDP began to decline in 2015, after a brief bounce following the 2008/09 recession. But absolute volumes will continue to increase in the developing and developed world because of rising GDP and population, and modern life’s dependence on plastics. The tide of waste threatening our ecosystems isn’t going to subside without determined action.

Can the materials industry learn from the energy transition?

Definitely. The energy transition started gaining traction once society recognised that climate change is a problem. That led to new policies (the Paris Agreement, as well as others at the national, state and even city levels); investment in technology and innovation (such as EVs and green hydrogen); and energy companies shifting strategic direction to embrace decarbonisation.

Belatedly, the penny dropped that plastic waste is a problem. There’s now policy (plastic bag bans, the EU’s 2019 Single-Use Plastic (SUP) Directive, among others) and technology advances (light-weighting cars and packaging, chemical recycling); while companies have begun to source recycled feedstock. But there’s not enough action across all fronts. Policy makers and the industry need to push harder to catch up with their peers in energy.

What can companies do to instigate change?

Packaging presents a major problem for the plastics industry in terms of environmental and reputational damage. Packaging companies need to start aligning the business model with the three ‘R’s: reduce (using less plastic in soft drinks bottles, for example); re-use (multiple-use packaging) and recycle.

Plastic can trump glass or aluminium on environmental grounds because manufacturing it emits less CO2 and uses less water. But the successful company of the future will work out how to collect and process the waste plastic to recycle it back into the value chain. There’s a cost, but it’s now happening. Nestlé has earmarked US$2 billion to pay for the higher cost of recycled inputs.

How much plastic is recycled today?

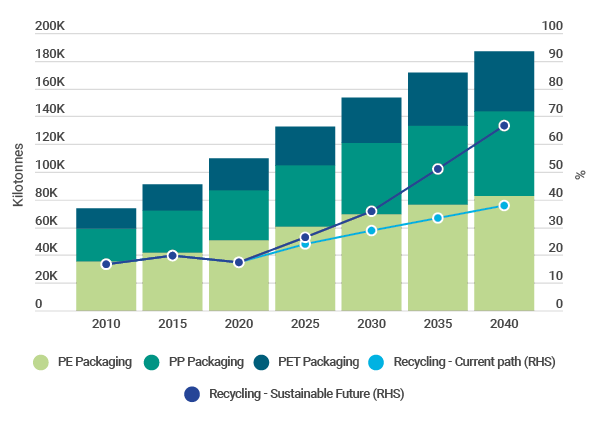

It’s pretty modest – across the board, around 10% to 12%. If we focus on the three main polymers used in packaging – polyethylene, polypropylene and polyethylene terephthalate (together, 85% of plastic packaging) – about 17% of feedstock is recycled plastic. Assuming a gradual increase in waste collection rates consistent with today’s trends, we’d expect recycling to rise to about 40% by 2040.

What could make things move faster?

There are two essential drivers in our more aggressive ‘sustainable future’ scenario. First, binding global regulatory targets using the EU’s SUP Directive as a model. Second, new policy sparks investment into technologies, such as chemical recycling, as well as new capacity post-2030 to enable the recycling of a much wider range of harder-to-recycle applications. We think recycling rates could reach as high as 67% by 2040, keeping 53 million tonnes of packaging materials from waste, whether landfill or the oceans. But we need to see action soon to make this happen.

What are the implications for oil demand?

Potentially significant. The petrochemicals industry already accounts for 13 million b/d of global oil demand and is the main driver of demand growth for the next two decades. The 83% of plastics production that doesn’t come from recycled feedstock is made from naphtha or natural gas liquids. If plastic recycling reaches 67% under our sustainable future scenario, it would take 1.5 million b/d a year from global oil demand by 2040.