The roadmap to recycling polyolefins

The future of polyolefin recycling hinges on innovations in waste management systems and a new kind of value chain.

3 minute read

Husam Taha

Principal Analyst, Plastics Sustainability

Husam Taha

Principal Analyst, Plastics Sustainability

Latest articles by Husam

-

Opinion

Plastic demand could reduce by up to 30% in an accelerated energy transition scenario

-

Opinion

The roadmap to recycling polyolefins

-

Opinion

Can private value chains boost polyolefin recycling?

For a long time, landfilling was the easy option for global waste management, but times are changing rapidly. Sites are overflowing, and with a global shift towards sustainability, industries are coming together to transform waste into a useful resource. For more details on recycling trends, the value chain, and regional differences, fill in the form to read the full report or continue reading for an introduction.

Relationships will be key

The pressures of the coming years will change the shape of business. If companies are to hit their net zero targets, they will have to diversify their portfolios and value chain activities through new partnerships and collaborations.

Relationships between producers, brand owners and waste management companies will be a powerful new currency, they will secure the flow of sustainable material from waste into products with high reuse value.

As expertise comes together, the value chain will be able to react more quickly to changes and challenges. These new partnerships will be focussed on acquiring stable long-term access to feedstock at low costs – having control over quantities and qualities of feedstock will put players in a competitive position as the industry scales up.

The value chain

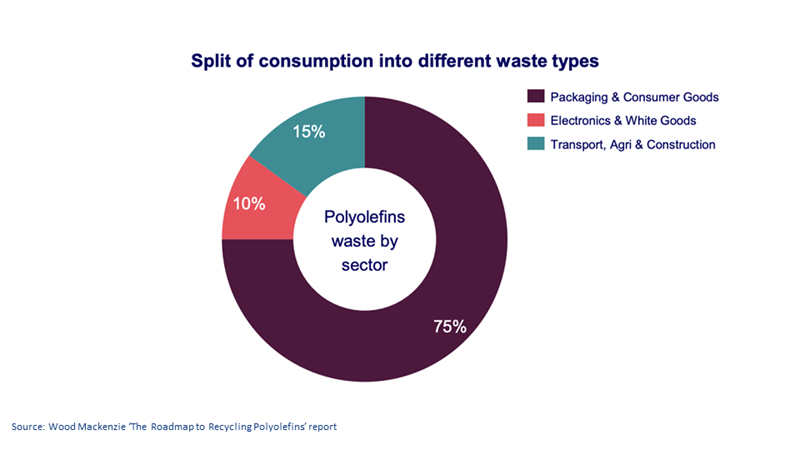

Waste is streamed into specialised collection and handling systems, but the existing recycling infrastructure is predominantly designed for post-consumer waste. Electronics and white goods are tricky: not normally built with circularity in mind, they often end up as impure plastic waste.

Transport, agriculture and construction have the same issue: a complex and intermingled waste product. With scrap yards and demolition sites generally valuing other materials, like metals, more highly than plastics, there isn’t much incentive to develop recyclable versions of many goods.

Recycling the unrecyclable

Ideally, recycling should be considered before landfilling or incineration, but only a third of the 200 million tonnes of polyolefins produced in 2022 are suitable for mechanical recycling. Fortunately, waste considered non-recyclable, can be processed chemically.

Innovation in the area of chemical recycling is beginning to accelerate, giving support to the industry in terms of operation rates and improved yields. The industry is likely to capitalize on the widely available flexible waste until 2030, from there on rigid feedstocks are likely to become more attractive from a cost and quality perspective.

As sorting technologies improve, materials will be swiftly paired to their appropriate recycling method, and higher yields and improved operational efficiencies should be the outcome. Chemical recycling methods will mean less material diverted into landfilling and incineration, gradually increasing the amount of material available to the circular economy.

The global value of waste

In the coming years, a global infrastructure will develop around exporting, importing and sorting waste. Net exporters in Europe and North America will have to effectively connect with waste-handling regions or develop the technology in-house. With the growth of chemical recycling, waste may begin to be seen as a desirable resource, potentially contributing to a decline in exports as countries decide to reap the benefits of their waste.

Asia will continue to be the main receiver of waste for a while, however, with plastic bans on the horizon, everything could change quickly. Southeast Asian countries were a favourite destination for plastic waste from developed countries, but Thailand is now counting down to a complete ban on plastic waste imports, and Vietnam and others will follow suit. Japan, South Korea and Australia are soon have to come up with domestic solutions.

New targets worldwide

Increasingly, legislation is bringing about a global reduction in plastic waste. In theory, these rulings should encourage investment in the circular economy, though in practice they are not all as effective as they could be. Canada has introduced a federal ban on single-use plastic, and ‘Plastic Pacts’ throughout the region set aggressive targets for the coming years.

Elsewhere, the picture is similarly mixed. In the US there is a high ambition, but there are feasibility concerns and a lack of clear-cut regulatory processes in place to complement the rise of advanced recycling facilities. High carbon taxes around Europe are beginning to incentivise plastic recycling, and between the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) and the new carbon taxes, mismanaging plastic waste and incineration will become more expensive.

As a result of these new incentives, fast-developing sorting and recycling tech, and a new, relationships-driven waste supply chain, the next few years could see more efficient, effective processes taking over the global plastic recycling industry – but there is some way to go, first.

For more detail, and to find out all about Wood Mackenzie’s Recycled Polyolefins Service and Materials Application Platform (MAP), fill in the form to read the full report.