The energy transition will be built with metals

Getting to grips with supply of the Big 5

2 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

Electrification is front and centre in the energy transition. The entire power value chain – from wind turbines and solar panels, transmission and distribution infrastructure to energy storage and batteries, electric vehicle charging and the rest – will be a winner.

But what does this mean for the metals that will build the plant, infrastructure and zero-carbon technologies? How much is needed and, critically, when depends on the pace at which the world pushes to reduce carbon emissions.

In any scenario, demand for metals goes up. But a 2 °C or lower pathway will require a more than doubling in power sector capacity over the next 20 years and will be truly transformational for metals. Julian Kettle, Vice Chair Metals and Mining, shared his views about the challenges for the sector in meeting rising demand.

What metals will we need?

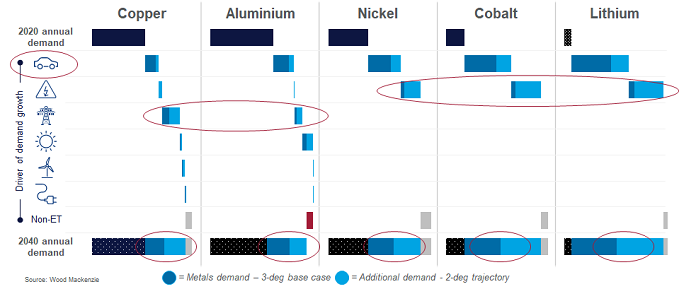

The big five transition metals are copper, aluminium, nickel, cobalt and lithium. The biggest growth sector will be electric vehicles – a 2 °C or lower pathway will see demand soar from 5 million vehicles today to at least 80 million by 2030. The EV body will heavily rely on aluminium to minimise weight, and copper for wiring. The batteries for EVs and the emerging energy storage market will drive up demand for lithium, nickel and cobalt. Copper and aluminium are critical to the expansion of transmission and distribution grids, as are solar panels.

How much more will we need?

Even in our base case, which is aligned with the less ambitious 3 °C pathway, demand growth will be substantial. We’re forecasting copper and aluminium demand to increase by about a third by 2040, nickel by two-thirds, and cobalt and lithium by 200% and 600%, respectively. A 2 °C or lower pathway doubles those growth rates.

The China of early this century offers the only comparable explosion in demand for metals and mining in living memory. That was more about iron ore, and demand rocketed to a new plateau as China began its prolonged investment in national infrastructure. For some metals, the energy transition could be like the Chinese economic boom on steroids.

Growth in EVs, energy storage and wires will transform demand for the big 5 transition metals

Are there political risks to metals supply?

The main concern is cobalt. The world will become increasingly dependent on the Democratic Republic of Congo which will control 80% of global supply by mid-decade. Battery makers are investing heavily in thrifting to reduce the proportion of cobalt in batteries, and in new battery chemistries to mitigate the risk.

What’s it going to cost?

Call it a conservative US$1 trillion over the next 15 years to ramp up the supply just in these five essential metals. We reckon copper needs US$525 billion over the period, aluminium US$335 billion, and nickel US$150 billion – double the investment on each over the last 15 years. Spend on new supply for lithium (US$50 billion) and cobalt (US$5 billion) is of a smaller order. But the industrial scaling-up of these metals for the 21st century economy is reflected in the six-fold increase needed in cobalt supply and 15-fold increase in lithium.

Where is the money going to come from?

Metals markets are currently at a low ebb, with demand and price weakened by the economic fallout from the pandemic. Our view is that we are two to three years away from any sustained economic recovery and the higher prices to incentivise investment in new supply. Metals has always been a highly cyclical industry and in this downcycle the sector has embraced capital discipline. It’s all about cash generation – there’s no appetite for risk or for investing in future growth through the downturn.

Although the energy transition is a golden opportunity for miners, few will commit capital to new supply when the timing of the pick-up in demand for the transition metals is so uncertain. Among the other risks is how carbon taxes will affect the economics of mining and processing operations, which can be extremely carbon-intensive.

Getting the timing right for new investment is a challenge given all these uncertainties. This presents a problem – it can take five to seven years to get a new mine into production. We’ll need decisions to sanction new projects made sooner rather than later.

Can the metals industry expect fiscal support?

Not as directly as the energy sector might be incentivised to develop new technologies like green hydrogen for hard-to-decarbonise sectors. But there are initiatives that could clear the path for miners, among them: stable policy on ‘green deals’ that help underpin demand, transparent policy on carbon tax and the mitigation of country risks, including ESG, that dissuade the major miners from investing.