The Euro Majors’ big bet on new energy

How to show value in early-stage renewables growth

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Upstream’s mounting challenge to deliver future oil supply

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

The European Majors have set bold targets to be net carbon-neutral by 2050. Progressively decarbonising and shrinking oil and gas is one part of it. But the strategy to invest in the zero-carbon value chain is the big bet on long-term corporate sustainability and relevance.

New energy businesses are being built from scratch, and most investment in the next few years will be in renewables. Wind and solar are among the few zero-carbon technologies that are already commercial, scalable and have some synergies with the oil and gas business. Valentina Kretzschmar, Vice President, has just launched our Corporate New Energy Series covering the six leading European players – Shell, Total, BP, Eni, Equinor and Repsol. She talked me through how she sees the businesses developing.

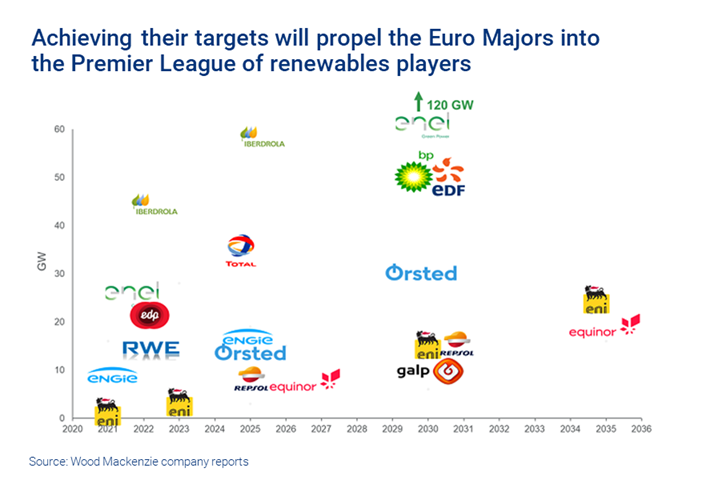

First, the Euro Majors are rapidly establishing meaningful renewables positions. New energy businesses emerged after the Paris Agreement five years ago, but not much happened with oil and gas in the midst of a downturn. By 2018, there was just 7 GW of capacity across all seven Majors, 2% of global capacity, and half was the legacy assets of BP and Total from a decade or more earlier.

Fast forward to today and all six companies have plans that will propel them into the premier league of global renewables players. Eni is targeting 25 GW by 2035, Equinor 16 GW (2035), Total 35 GW (gross, 2025) and BP 50 GW (2030), while Shell has no specific target. BP’s 50 GW, if achieved, would give it 1.5% of global renewable power capacity, only just lower than its share of global oil and gas production.

Second, the growth opportunity in renewables is huge. We forecast capacity will triple to 3,700 GW by 2030, with 2,450 GW of new build – 1,600 GW of solar, 700 GW onshore wind and 150 GW offshore. That’s 200 to 300 GW of new capacity additions every year for the foreseeable future.

What’s surprised us is how quickly the Majors have managed to build exposure. Together, the six companies have accessed around 15 GW in 2020 with an even spread across solar and wind. Much of it is very early stage and acquired for little upfront capital outlay.

Total has accessed 10 GW globally this year alone, trebling its exposure through a focus on early-stage opportunities. Offshore wind is fast becoming a focus for Majors, drawn by the scale and in a field where they can leverage capital and project execution skills. Total and BP picked up assets in 2020 and Equinor has focused almost exclusively on offshore wind.

Third, the renewables cash flow profile is highly attractive to the Majors. If the returns are typically more modest than oil and gas, so, too, is the risk. And the shape of cash flows looks similar to long-life upstream gas assets – heavy investment for two or three years, then 20 years or more of stable production.

The big difference is that projects that secure a PPA (power purchase agreement) can virtually guarantee stable cash flow for 10 to 15 years of the asset life, which can exceed 20 years. It’s highly bankable and a dependable future source for shareholder dividends.

We expect the Majors will aim to maximise PPAs as they develop assets; though intensifying competition for contracts will put downward pressure on contract prices and returns. Over time, some may look for wholesale price exposure, leveraging energy trading to enhance returns.

Leaders Total and Equinor have already assembled portfolios that could generate 10% to 20% of group cash flow post-2030, higher still if they hit their capacity targets. The early years of build out, though, will consume a lot of capital.

Our company cash flow modelling suggests that new energy businesses will be free cash flow-negative for most of this decade. We’d expect the companies to look at all financing options, including project finance and monetising equity exposure, by ‘flipping’ de-risked assets – there’s no shortage of risk-averse buyers looking for green assets. Even so, the capital demands of growing a zero-carbon business underline the importance for legacy oil and gas to serve as a cash cow.

Fourth, investors have been prepared to pay a big premium for renewables’ growth and ESG credentials. The share prices of European pure play Orsted and utilities, such as Iberdrola, with significant renewables exposure have doubled in the last two years and trade on significantly higher multiples than the European oil majors. This presents an opportunity for the Euro Majors with new energy aspirations to score a premium rating.

Repsol signalled this week that it is considering tapping lower cost capital and demonstrating value by IPO-ing its renewables business or selling a minority stake. They’ll all want to do this. We’d anticipate a rerun of the early 2000s when a clutch of European utilities – Iberdrola, EDF and EDP among them – successfully spun-off their early-stage renewables businesses.

Back then, renewables were the coming thing, but marginal in the grand scheme of things. Now it’s the thing – the big growth theme of the energy transition that’s investable today. And there’s seemingly a wall of money wanting to buy into it.

Explore the emerging energy transition landscape

The Corporate New Energy Series is a collaboration between Wood Mackenzie experts from the corporate, energy transition practice and carbon research teams. Find out more.