Offshore wind propels the UK’s net zero ambitions

The UK is home to around 35% of the world’s installed offshore wind capacity. Technology evolution will be vital to maintain the growth of the sector.

1 minute read

Malcolm Forbes-Cable

Vice President, Upstream and Carbon Management Consulting

Malcolm Forbes-Cable

Vice President, Upstream and Carbon Management Consulting

Malcolm is an expert in strategy development, transaction support and the energy transition.

Latest articles by Malcolm

-

The Edge

No country for oil men (and women)

-

Opinion

The Norwegian emissions dilemma

-

Opinion

The case for developing UK's oil and gas resources: Rosebank and Cambo fields

-

Opinion

Scotland the brave: a Firth of Forth net zero hub for COP26?

-

Opinion

A £2.5 trillion transformation: the economic impact of a net-zero North Sea

-

Opinion

Is net zero oil and gas production possible?

Wind is an abundant resource on the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS), and will play a vital role in realising the UK’s ambitious 2050 net zero emissions target. But are offshore renewable targets on track? Are there innovation gaps that need to be closed? And will the UK forge a path that other regions can follow?

This is the first in a five-part series of articles exploring the Wood Mackenzie/OGTC report, Closing the Gap: Technology for a Net Zero North Sea. Fill in the form to download the chapter on the renewable energy ecosystem and the path to 2050. Or read on for a summary of some of the key themes.

The UK is a world leader in offshore wind

Offshore wind is a key feature of the UK’s net zero future. It’s off to a good start, with more installed capacity than any other country. This leading position is down to strong wind speeds, shallow water depths and appropriate seabed substrate – combined with early adoption, technology evolution and clear political will.

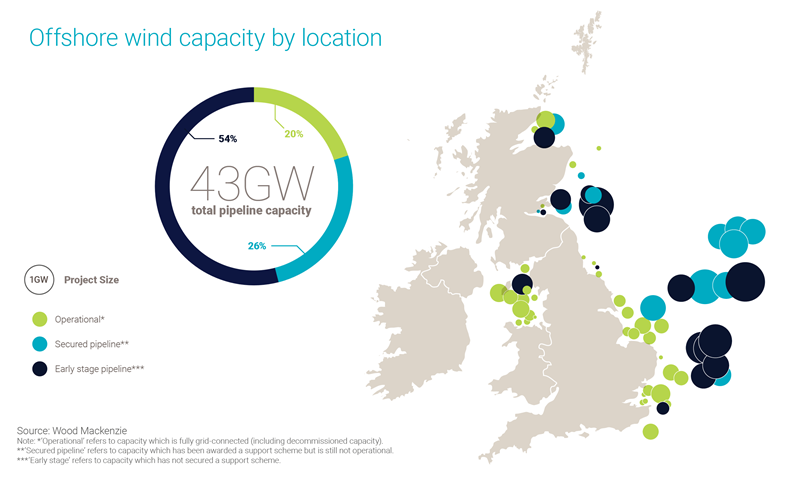

At the end of 2019 the UKCS had an installed capacity of 8.6GW across more than 35 operational offshore wind projects. In 2020, offshore wind is expected to generate 10% of the UK's electricity. The government aims to reach 40GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030 and looks on target to do so. It is worth noting that this target could be accelerated when the government unveils its latest package of green energy policies.

The UK offshore wind market has attracted global interest

While 32% of its major suppliers are based in the UK, 68% of the offshore wind supply chain is sourced from non-UK based firms.

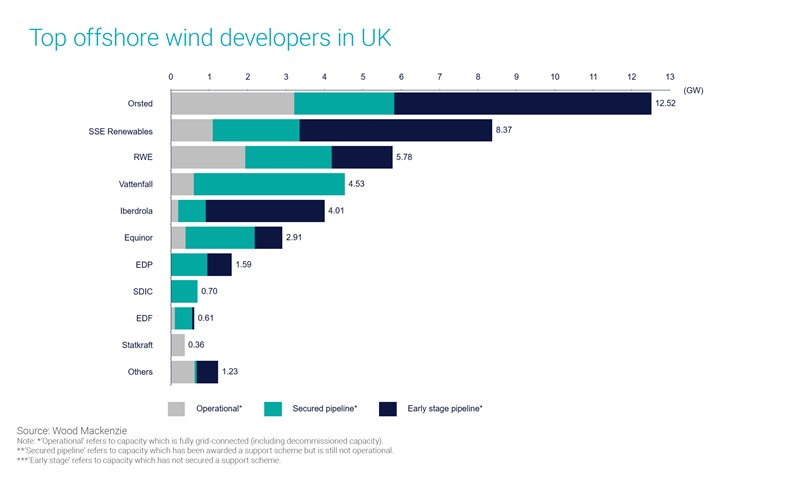

Key players include UK-based SSE, one of the most active wind developers and operators in the region, and Danish company Ørsted, which currently has the largest UK offshore wind portfolio. RWE, Vattenfall, Iberdrola and Equinor also have large UK offshore wind portfolios.

Other major energy players are showing an interest in the UK's offshore wind sector. For example, in March 2020 Total entered the UK floating wind space when it acquired a stake in the Erebus project in the Celtic Sea.

The decarbonisation of the UKCS will continue to attract interest from the global energy industry, with investment fuelled by the increasing availability of finance for green projects. It’s a huge opportunity for Big Oil as they seek to establish a foothold in offshore wind and other zero-carbon technologies, and transition to Big Energy.

Turbine technology must evolve as wind farms move further offshore

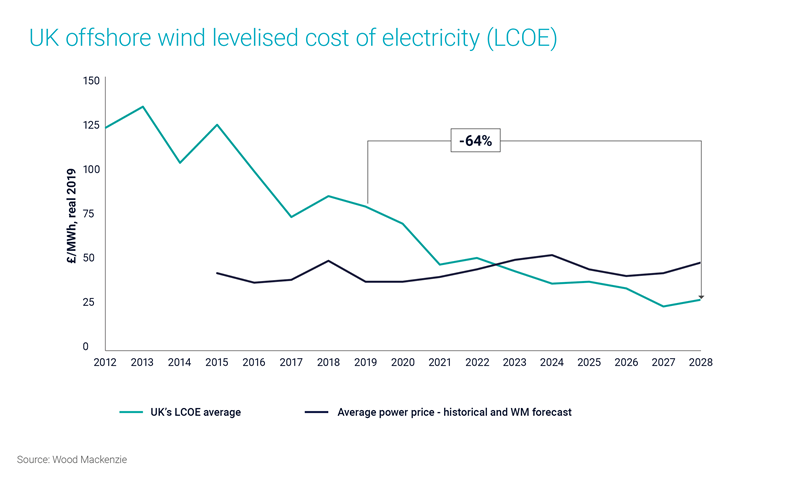

There are headwinds. Worsening area characteristics is one key barrier to the growth of offshore wind. Most easy-to-access, shallow water locations are already licensed and projects in more complex areas will incur higher capital costs. However, the UK’s offshore wind levelised cost of energy (LCOE) has nearly halved since 2012. And it’s expected to drop further as technology improves, the demand outlook steadies and the economies of scale take effect.

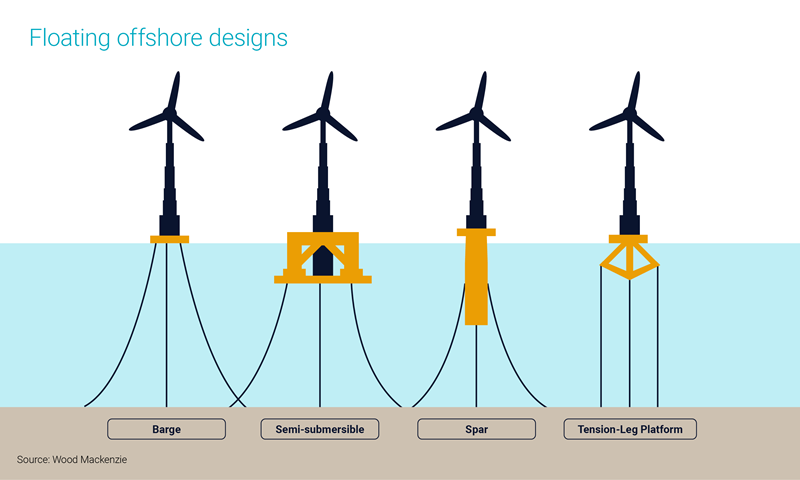

New and improved technology will be crucial. The UKCS is currently home to around 35% of the global installed offshore wind capacity, almost exclusively from fixed-bottom turbines. But around 80% of the UKCS’ offshore wind resource potential is at depths where fixed-bottom systems aren’t viable. The industry is therefore exploring the potential of floating systems – Hywind, the world’s first floating offshore wind farm, was installed 15 miles off Peterhead in Aberdeenshire by Equinor in 2017.

Floating wind has the potential to expand to 10GW of capacity by 2050. However, turbine design needs to be standardised to enable mass production – and policy-makers need to develop a clear route to market for the industry to take off at commercial scale.

What are the challenges in designing ever-larger, yet durable and reliable turbines? Are innovation gaps on track to be resolved? What other barriers stand in the way of growth? Fill in the form on this page to find out more about the evolution of UKCS wind energy.

The UKCS could also become a hotspot for marine energy

In 2018 the UK produced 8GWh of electricity from marine energy, less than 0.003% of the total electricity generated in that year. But it’s estimated that the UKCS and its estuaries and streams could provide a marine energy resource of 16,000 GWh per year. And this resource could be coupled with wind to balance power output.

Several challenges stand in the way. Marine energy’s high upfront costs, suboptimal durability in subsea environments and maintenance challenges hamper economic feasibility.

How are tidal and wave energy technologies evolving? Fill in the form to read more about UKCS marine energy.

Transmission and storage infrastructure are critical challenges

Across all offshore renewables, the main technology challenge lies in developing transmission infrastructure in the short term, and energy storage in the long term.

Transmitting power to the UK market will become increasingly complex as wind farms move further offshore. Today, most offshore wind farms are connected to the grid by an AC cable, but installations further out will require other technologies. The Dogger Bank project currently in development, for example, will utilise high voltage direct current (HVDC), which is expected to mitigate energy transmission losses and could also lower construction costs.

Energy storage will become more important as offshore renewable capacity grows. Currently, renewable energy generation doesn’t exceed demand at any instant. But it will become increasingly challenging to fully utilise generation capacity, and maintain reserves for peak demand, without enhanced system flexibility.

How is system flexibility currently managed? How will battery advances support the sector? And is green hydrogen the key to seasonal storage? Fill in the form to find out more.

All eyes on the UKCS?

With the largest installed offshore wind capacity in the world all eyes are on the UK as other jurisdictions look to decarbonise and diversify their energy supply.

There is much to be learnt from the UK’s experience and a lot to follow as licensing, turbine installation and technology advances develop at pace. Other regions will gain valuable insight from the UK’s successes – and any missed opportunities – as they develop their own sustainable integrated energy networks. There is a material opportunity for countries to harness natural resources to deliver sustainable, low-cost power to their economies. That’s what makes our report into how the UK is tackling this complex challenge such essential reading.

To find out more, read the renewables chapter of our report, Closing the Gap: Technology for a Net Zero North Sea. This includes:

- Renewable energy ecosystem and the path to 2050

- Speculative technologies for renewable energy

- Renewable energy technology roadmap.

Fill in the form at the top of the page for your copy.