The Majors have got bigger – but are they better?

Understanding the Majors' upstream transformation

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

Big Oil has got bigger – a lot bigger. The Majors have increased commercial reserves by 62 billion boe (proven and probable) through the downturn, equivalent to another BP and Chevron combined. Our forecast for 2030 production for the seven companies is over 6 million boe/d, or 40% higher today than it was in our 2014 view.

It seems counterintuitive for an industry facing lower-for-longer prices and the threat of progressive decarbonisation. Has all this growth better equipped Big Oil for these challenges? The Corporate Analysis team has just published the Majors’ Upstream Transformation. I turned to Tom Ellacott, senior vice president, for answers.

How have the Majors transformed their portfolios in recent years? Purchase the report in store to find out.

The Majors' upstream transformation

Buy nowAre the Majors chasing volume rather than value?

No, far from it. Cash generation is paramount – cost-cutting and productivity gains have driven cash flow breakevens down from US$63/bbl in 2015 to an average of just US$40/bbl today.

We’ve also seen a profound strategic shift with companies building resilience into portfolios. In the past, Majors built reserves during a downcycle to increase leverage in anticipation of a price recovery that would inevitably follow. This time, the focus has been to secure future production that’s low cost, high margin and protects against uncertainties. We’d say the Majors aren’t just bigger but are also in far better shape.

So what are they betting on?

First, tight oil is the biggest theme. Our forecasts have increased by 2.5 million boe/d since 2014, transforming the outlook for Chevron and ExxonMobil, the leaders in this asset class. Deepwater is second with an increase of 1.6 million boe/d. What’s surprising is that gas accounts for well under half of the 2030 production increase (38%). Downgrades to commercial volumes of US unconventional gas have offset strong growth in LNG. The Euro Majors have got gassier, but the higher tight oil volumes have diluted gas exposure for the US Majors.

You may also be interested in:

- How can Big Oil stay investible through the energy transition?

- Can the energy industry rise to the challenge of climate change?

- Majors' renewables project tracker

How did they do it?

They’ve pulled every lever. Of the 62 billion boe reserves added, around one-third came through acquisitions, one-third through exploration and discovered resource access, and another third through ‘reserve growth’ from existing assets. It’s that last bucket that’s really impressed. New ways of thinking and working have allowed the Majors to unlock an additional 19 billion boe of conventional and tight oil resource from within the portfolio. These volumes are a prize worth chasing – generally high value, low risk and with zero cost of entry.

What about returns?

Capital discipline is still the mantra. Big Oil is targeting double-digit full-cycle returns at US$55 – 65/bbl Brent. Anecdotally, we reckon hurdle rates have drifted towards the bottom of the range in 2019 as companies tighten up capital allocation criteria.

Value creation varies depending on the opportunity. Full-cycle economics on some large-scale discovered resource opportunities (DROs) and acquisitions won’t set the heather alight. Half-cycle or ‘point-forward’ returns look very attractive for certain thematics, notably Permian tight oil and some conventional projects. Full-cycle tight oil economics, factoring in acquisition costs, in contrast, can still be underwhelming.

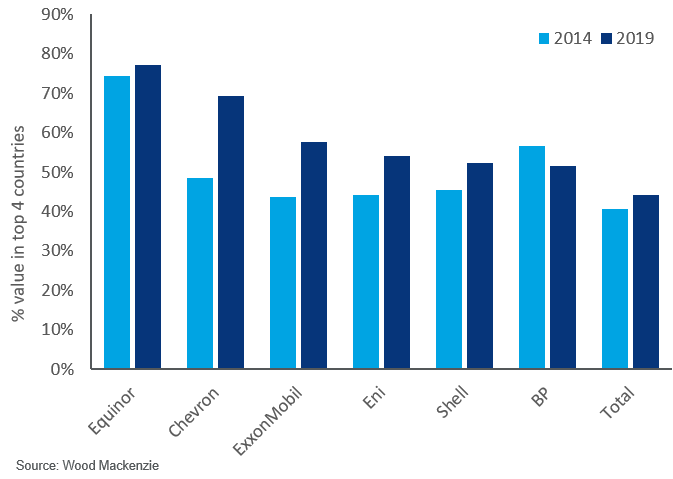

Does bigger mean less focused?

No, the opposite – we’re starting to see increasing portfolio concentration. The Majors are focusing on asset types or geographies where they have competitive strengths and competencies. The US Majors, for example, have significantly strengthened tight oil exposure. European Majors have used DROs, M&A and exploration to beef up advantaged positions in conventional plays. Eni has stood out with singular success in exploration. The US/European contrast can be overplayed – ExxonMobil has been very active outside the US while BP and Shell have expanded in US tight oil.

Increasing portfolio concentration in the downturn – only BP has bucked this trend

Do you expect more portfolio concentration?

We want to see more. There is a great opportunity to high-grade portfolios by selling non-core, mature and low-margin assets; as well as carbon-intensive fields. It’s a strategy that should appeal greatly to investors and other stakeholders. The bolder companies will engineer more sustainable, cash-generative portfolios by active, even aggressive, high-grading programmes. If that means downsizing – not delivering the 2030 production we forecast – then so be it. The value released from unwanted assets can either be returned to shareholders or re-invested in the business – to bolster advantaged E&P positions or, increasingly, in building exposure to zero-carbon opportunities.

Contact Tom with your questions about the Majors' upstream transformation

Tom Ellacott has led the analysis of over 40 companies in the corporate service, including all the Majors, leading Independents and the main Asian national oil companies.

Tom Ellacott, senior vice president, corporate research