The oil industry’s rapid response to the crisis

Deep cuts to investment and costs – are the Majors’ dividends sacrosanct?

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

View Simon Flowers's full profileIs crisis too strong a word? Not judging by the oil industry’s incisive response in the last week to the collapse in price. Brent is down by 50% already and may halve again in the coming weeks as demand falls and more Saudi and Russian supply comes onto the market.

What are companies doing in the face of the challenge? What more might they need to do? I chatted through these questions with Tom Ellacott and Erik Mielke of our corporate analysis team.

First, cash is king. Treasury is working 24/7 on liquidity. While most levers to save cash take time to have effect, raising money on the market is more instantaneous – assuming you can do it. Equity markets are effectively closed, debt markets all but. ExxonMobil was able to raise US$8.58 billion of medium- and long-dated debt last week to add flexibility as it navigates a period of committed heavy investment in its projects. But ExxonMobil is at the top of the credit rating tree. Further down, access to debt markets declines exponentially, the cost of debt rising in inverse proportion. It’s expensive, if you can get it.

Second, we’re seeing expenditure slashed and in double-quick time. Having learned from 2015/16, operators have moved quickly to send a message to investors and lenders that they are on it. US Lower 48 E&Ps, already under pressure to generate free cash flow prior to the price fall, have led the way.

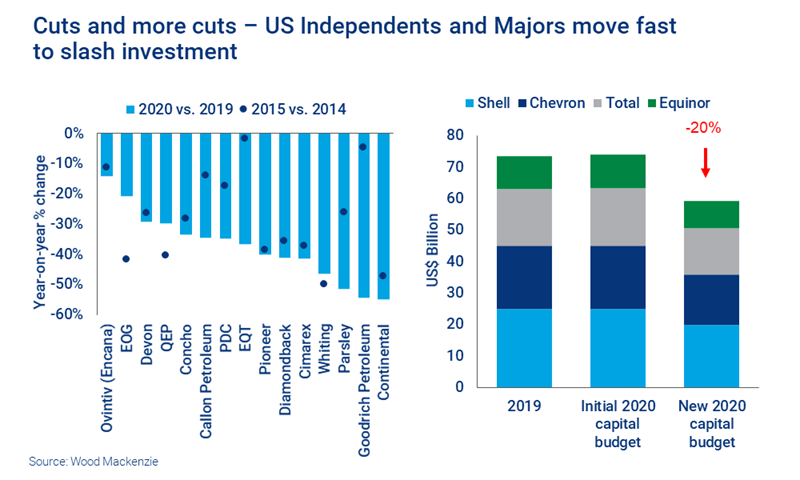

Two weeks in, 22 US independents have cut investment for 2020 by a total of US$20 billion, an average of 35%, and three by 50% or more. The size of cuts is close to those of 2015 and have come through faster. Yet companies today are far leaner than back then; and what we’ve seen so far may just be a taste of what’s to come. Diamondback and Occidental have already cut twice in two weeks, suggesting further, deeper cuts are coming for many US Independents.

Majors, too, have pulled the trigger quickly. Shell, Total, Chevron and Equinor have announced upstream budget cuts of 20%. BP has indicated a similar ambition and, along with ExxonMobil and Eni, will deliver granular plans imminently.

The Majors’ capital spend in 2020 will now be half that of 2014. The reduction reflects improved efficiency – each invested dollar goes a lot further today. But it’s also a fair indicator of upstream’s increasingly straitened circumstances over the last decade.

The crisis will precipitate a structural reset of operating costs. Shell has announced a target of US$3 billion to US$4 billion by year end, down 10%; Total has more than doubled its 2020 efficiency target to US$0.8 billion; Chevron and Equinor are aiming for US$1 billion operating cost reductions. The rest too will seize the opportunity.

Third, there are shareholder distributions. Buybacks will stop. The Majors and some Independents have used buybacks to return surplus cash flow to shareholders over the last few years. It’s a useful tool which can be switched on or off depending on market conditions. For now, it’s definitively off – Shell (US$4 billion), Chevron (US$5 billion), Total (US$2 billion) and Equinor (US$0.7 billion) have already shelved planned buyback programmes for 2020.

That leaves dividends – should the Majors keep paying? Dividends have not just been sacrosanct; they’ve become the equity story over the last several years as investment in growth has wound down. Back in 2014, the Majors spent US$4 on overall investment for every US$1 paid in dividends. The ratio has been falling and will slump to just US$1.75 to US$1 on the new, reduced capital budgets for 2020. The Majors are dividend machines, and investors depend on them. UK pension funds rely on BP and Shell for an astounding 20% of their total annual dividends.

Or should they cut? There’s a strong argument for it, the topic will be on most board agendas in a way that was unforeseeable a few weeks ago. Double-digit dividend yields (Shell 12%, BP 10%, ExxonMobil 10%) suggest that dividends may be unsustainable; but also that the high pay-out isn’t reflected in the stock market rating. The latter is a metric that boards generally cite in justifying a cut to retain cash in the business. And what better time to do it than in a wider economic slowdown when so many companies in other sectors will also be cutting. It’s a good time to bury bad news.

It's not a decision the Majors will take lightly or, for that matter, quickly. However challenging the outlook at the moment, things could look different in a few months’ time – for the better or the worse. And there is always the ‘half-way’ house, paying scrip dividends – preserving the pay-out, but conserving cash, an option some used with success after the last price collapse.