US policy cranks up the risks to oil supply – and price

Dwindling spare OPEC capacity leaves market vulnerable to disruption

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

US upstream gas sector poised to gain from higher Henry Hub prices

-

The Edge

What comes after the Permian for IOCs?

Geopolitics is never far from the fray. The oil market was chronically oversupplied a few months ago. Now Brent is back over US$70/bbl as tension builds around some of OPEC’s bigger producers. Could prices go higher? For the answer, I turned to Ann-Louise Hittle, VP Oils Research.

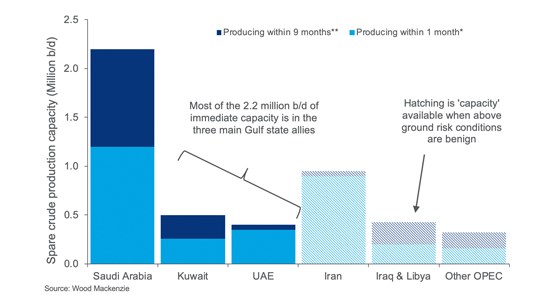

The US policy decision to throttle supply with simultaneous sanctions on Iran and Venezuela is fraught with risk. Yes, OPEC can meet the immediate shortfall, but that leaves precious little spare capacity if there’s more supply disruption.

Ann-Louise Hittle

Vice President, Oil Markets

Ann-Louise directs our Macro Oils Service and is a frequent contributor to numerous industry publications.

Latest articles by Ann-Louise

-

Opinion

Price swings ripple through North American oil markets

-

Opinion

Oil and refining market implications of Israel’s strike on Iran

-

Opinion

What is the impact of US tariffs on oil and refining?

-

Opinion

What the Middle East conflict means for oil, LNG and the global economy

-

The Edge

What the Middle East conflict means for oil and LNG

-

Opinion

Trump’s tariff plan: implications for the future of global liquids trade

What worries you most in the short term?

Rising geopolitical tension around Iran. The end of sanctions waivers will reduce exports from around 1.2 million b/d today to 0.7 million b/d this summer. That’s less than a third of what they were selling in 2017, and takes another 0.4-0.5 million b/d out of global supply, with only China and India still prepared to buy Iranian crude. Should the US succeed in its goal to reduce Iran’s exports to zero, it would worsen supply tightness materially. The other big concern is that as economic pressure bubbles up, Iran responds to US pressure with a knock-on effect for regional stability.

What about Venezuela and Libya?

The stalemate in Venezuela looks set to be protracted and the recovery of supply slower. We’ve cut our 2020 forecast to 0.83 million b/d, flat on 2019. So, through next year, Venezuelan production is a third of what it was in 2014. As for Libya, we just reduced our 2019 forecasts by 50 kb/d to 0.9 million b/d. The escalating civil war there shouldn’t be underestimated as a risk to global supply.

Meantime, the US keeps pumping

Yes, and dominating non-OPEC production growth. We forecast 1.9 million b/d of US liquids growth in 2019, only marginally down on last year’s phenomenal 2.2 million b/d. The Permian is the driving force, contributing two-thirds of this year’s increase. The bidding war for Anadarko underlines the attraction of Permian tight oil growth to Big Oil, and we’ll see more consolidation. The bigger companies have access to capital and have only just begun to industrialise the play. Permian volumes will grow year-on-year for the foreseeable future.

Is the rest of non-OPEC growing, too?

Overall, yes. Production outside the US stagnated in the immediate aftermath of the price crash. The industry adapted and cut costs, and supply is growing again. We forecast non-OPEC production outside the US to increase from 2018 by 1.2 million b/d by 2020, almost half what the US will deliver. The bulk is from new projects in Brazil, Canada, Australia and Norway.

Will demand growth absorb all the new supply?

No, but oil demand is ticking along quite nicely. We expect growth of 1.1 million b/d in 2019, accelerating to 1.5 million b/d in 2020 – assuming a gentle easing of global economic growth rather than a major slowdown. Asia and US petrochemicals provide much of the growth, with a recovery in the Middle East and Latin America, and the IMO in 2020, helping things along.

And OPEC+ is still managing the market?

It has to – to balance the market. Saudi Arabia and the UAE, the two biggest OPEC producers, have reduced production by about 1 million b/d from October 2018 levels. That’s more than twice the cuts they agreed to, and despite the loss from the market of 0.8 million b/d from Libya, Venezuela and Iran. The reductions in OPEC supply have brought the market into balance in 2019 – 1.0 million b/d of global supply growth versus 1.1 million b/d of demand growth. Without the fall in OPEC production, the market would be awash in crude and prices much lower.

What will OPEC+ do as Iran’s exports fall?

The market is on course to tighten in the third quarter, so Saudi Arabia is starting to lift its production to compensate. Presently, OPEC has around 1.8 million b/d of spare capacity that can be brought on stream within a month. The tricky bit will be timing – balancing the Saudi and others’ increases with the fall in Iran’s exports. That could mean price volatility through the transition period this summer.

Could prices go higher?

We expect Brent to hold a little over US$70/bbl in the coming months. But the US policy decision to throttle supply with simultaneous sanctions on Iran and Venezuela is fraught with risk. Yes, OPEC can meet the immediate shortfall, but that leaves precious little spare capacity if there’s more supply disruption. Mounting geopolitical tension is a real threat to oil market stability.