Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

A new Marshall Plan for energy

The US and EU still aim to tackle climate change. But cutting European imports of Russian gas is the immediate priority

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed Crooks

Vice-Chair, Americas

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

How global trade can help build the clean energy economy

-

Opinion

Biden exit shakes up US presidential race

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

Opinion

Are low profits to blame for the energy transition lagging?

-

Opinion

Day 3: How can we finance the energy transition? Discussions from the final day of the Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

-

Opinion

Day 2: The Energy Gang at The Reuters Global Energy Transition Conference 2024

Energy played a key role in the Marshall Plan, implemented by the US between 1948 and 1951 to help rebuild the shattered economies of Europe. More than 10% of the aid under the plan’s European Recovery Program was spent on oil, and 56% of the oil bought from American companies by recipient countries was financed by US government agencies. So it is fitting that as US and European leaders have been thinking about strengthening their energy relationship as a response to the crisis in Ukraine, the Marshall Plan has been on their minds.

Jennifer Granholm, the US energy secretary, last Wednesday said in a speech at the International Energy Agency’s ministerial meeting in Paris: “I think it’s a moment for us to ask at this point in our history, what is going to be our version of the Marshall Plan for clean and secure energy in 2022 and beyond?”

President Joe Biden and Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, on Friday gave a sense of what that would mean. They announced an initiative to reduce Europe’s imports of Russian energy, intended to help achieve the EU’s goal of ending those imports altogether by 2027. Like the Marshall Plan, it is a programme that is not purely altruistic for the US. Achieving its goals will both serve US strategic interests, and expand markets for American exporters.

In the short term, the EU-US initiative may not have much impact. The two sides are aiming to “ensure additional LNG volumes for the EU market” of at least 15 billion cubic metres this year, from the US and its allies. US LNG exports have ramped up in recent months as Cheniere Energy’s Train 6 at Sabine Pass, and Venture Global’s Calcasieu Pass plant, have come on stream. Calcasieu Pass sent out its first cargo on March 1. There are no new projects scheduled to start exporting from the US before 2024 at the earliest.

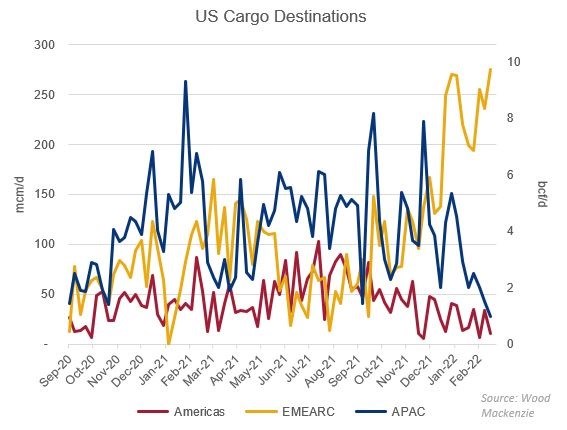

Some LNG can be diverted to Europe from other markets, and will be diverted if the prices are right. But roughly seven out of ten LNG cargoes leaving the US are already bound for Europe (see ‘Chart of the Week’, below), so there may not be much more scope to point gas in that direction. If all that is happening is that more gas flows to Europe because price signals point that way, and there is little additional LNG being brought into the global market, then it will not do much to relieve the pressure on Europeans struggling to manage high energy costs. That will be true even if EU member states try to hold down the cost of gas by buying jointly.

In the long term, however, the effect could be much more significant. The EU-US initiative also sets a goal of ensuring demand in Europe for an additional 50 bcm a year of additional US LNG, until at least 2030. That represents about 36 million tonnes of LNG per year, which would be an increase of about 40% on top of the export capacity already on stream in the US.

It is perfectly realistic to think that this scale of growth could be achieved over the next few years. Alex Munton, Wood Mackenzie’s principal analyst for US LNG, expects three projects — Golden Pass, Plaquemines and Corpus Christi Stage 3 — to come online in 2024-25, with a total of some 40 mmtpa in capacity. Venture Global is closing in on a final investment decision for its Plaquemines LNG project, and last week signed a sale agreement for gas from the project, this time with New Fortress Energy.

There are about 20 other North American LNG export projects under development, and some of those could well be available to help meet that goal for increased supplies by the end of the decade. It has taken Cheniere and Venture Global only about 30 months from final investment decision to first gas shipments.

The extra 50 bcm / a year offered by the US would only cover about a third of the 155 bcm / year of imports from Russia that EU leaders want to replace. But in the context of a larger European strategy to find alternative supplies of gas, both pipeline and LNG, and to curb demand, US exports could make a significant contribution.

Tackling climate change remains an objective

Both the Biden administration and the EU emphasised that their plans to boost US LNG production and exports to Europe did not mean they were abandoning their goals for cutting greenhouse gas emissions. The joint statement argued that policies to meet the objectives of the Paris climate agreement, including “a rapid clean energy transition, renewable energy, and energy efficiency,” could also “contribute to making the EU independent from Russian fossil fuels”.

At times, however, the imperatives of climate policy and energy strategy can conflict, as they did with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s recent policy statement on approvals for proposed gas infrastructure such as pipelines and LNG plants. The commission last month published a new framework for these decisions, saying it would take greenhouse gas emissions impact into account when deciding whether or not a proposed project was “in the public interest”.

That new framework — a response to court rulings striking down earlier FERC approvals — would increase the burden of compliance for developers by forcing a rigorous assessment of effects on greenhouse gas emissions, and measures to mitigate those emissions if necessary. FERC originally said that it would be consulting on the rules, but would be enforcing them as an interim measure while the consultation was under way.

Last week, the commission announced that “after further consideration”, the climate policy framework, and another related set of rules on local pollution, would be designated merely as draft policy statements for public comments, and would not apply to any pending or new applications filed before it has come up with final guidance. If the new rules had continued to be applied immediately, FERC would have stood in glaring contradiction to the Biden administration’s commitment to “maintaining an enabling regulatory environment”, to allow new LNG export capacity to receive permits “expeditiously”.

The US and EU are trying to reconcile climate policy with energy security by curbing the greenhouse gas emissions from new fossil fuel production as far as possible. The EU-US initiative includes a pledge to reduce the greenhouse gas intensity of all new LNG infrastructure and pipelines, using techniques such as cutting methane leakage and using renewables to power operations. They also talk about making sure that new gas infrastructure is “hydrogen ready”.

The other way the US can help is with increased exports of lower-carbon energy technologies such as heat pumps and electric vehicles, and in the longer term small modular nuclear reactors and long-duration battery storage. A group of Democratic senators led by Edward Markey and Elizabeth Warren wrote to President Biden to make this argument last week, looking not to the post-war Marshall Plan but to the wartime Lend-Lease programme as a model: the US government financing exports of vitally needed equipment.

The administration has not yet backed that type of plan, but as the new joint EU-US Task Force for Energy Security gets to grips with the scale of the challenge involved in shutting off Europe’s energy imports from Russia, some of the more radical options may be have to be put on the agenda.

In brief

Kazakhstan expects the Caspian Pipeline Consortium to resume exports from its terminal on the Black Sea coast of Russia within a month, the country’s energy minister has said. Loadings at the terminal have been disrupted after reports of storm damage to berths at the port of Novorossiisk.

The city of Shanghai has begun the first stage of a lockdown in an attempt to limit the spread of Covid-19, raising the prospect that energy demand could be hit. However, reports suggested most factories continued to operate as usual. Shanghai will be shut down in two stages, affecting first the east and then from Friday the west side of the city.

The conflict in Ukraine has put an end to the globalization of the world economy, BlackRock chairman Larry Fink argued in this latest letter to shareholders. He also suggested that in the longer term, “recent events will actually accelerate the shift toward greener sources of energy in many parts of the world.”

Other views

Simon Flowers — Upstream cash machines

Vanessa Witte and Chloe Holden — US battery storage deployment doubles in a single year

Quote of the week

“I was robbed at a gas station in NJ last night. After my hands stopped trembling.. I managed to call the cops and they were quick to respond and calmed me down... My money is gone.. the police asked me if I knew who did it.. I said yes.. it was pump number 9.” — The rapper Ice-T posted a widely-shared joke that resonated with Americans’ discontent over rising fuel prices.

Chart of the week

This comes from a recent Wood Mackenzie note on global gas and LNG markets. It shows destinations for US LNG export cargoes over the past 18 months. You can see how this year, the great majority of US LNG exports have gone to Europe, with shipments to Asia and elsewhere in the Americas running below last year’s levels. As of March 23, 36 US LNG cargoes were going to Europe, while 14 were en route to Asia, and 3 were going to the Americas. The premium in European gas prices has been overwhelmingly attracting US exports in that direction.