Sign up today to get the best of our expert insight in your inbox.

Gas contracts central to Nord Stream pipeline mystery

Responsibility for the attack last September remains unknown. It could be crucial for multi-billion dollar arbitration claims

14 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

Latest articles by Ed

-

Opinion

Ceasefire in the Israel-Iran conflict

-

Opinion

The impact of the Israel-Iran conflict escalation on the global energy market

-

Opinion

EBOS: the unsung hero that’s accelerating clean energy deployment

-

Opinion

What the US attack on Iran’s nuclear installations means for energy

-

Opinion

How do we adapt to a warming world?

-

Opinion

What the conflict between Israel and Iran means for energy

"A wise man,” wrote the Scottish philosopher David Hume, “proportions his belief to the evidence.” Hume was one of history’s greatest sceptics, who argued that beliefs should always be based on experience and reason. In today’s world of viral misinformation, his ideas are more valuable than ever.

The attack last September on the Nord Stream gas pipeline system, which runs for about 750 miles from Russia to Germany, has fueled an enormous amount of speculation and theorising. This week, those theories reached the United Nations Security Council, after Russia demanded a debate on the incident, and called for a UN inquiry.

Russia’s demands followed a report by the veteran investigative reporter Seymour Hersh, claiming that the US, with support from Norway, had sabotaged the pipeline in a “covert sea operation”. Vassily Nebenzia, Russia’s ambassador to the UN, said this week that thanks to Hersh’s story “we found out not only that the US did it, but how they did it.” There was, he added “no doubt as to the fact that the American journalist is telling the truth.”

The US has described Hersh’s story as “false and complete fiction”. John Kelley, the US ambassador to the UN, this week said that Russia’s call for an inquiry was “a blatant attempt to distract” from the forthcoming meeting of the UN General Assembly marking a year since the invasion of Ukraine. Other journalists and analysts have challenged many of the operational details in Hersh’s report.

Eventually more evidence may emerge to clarify our understanding of the attacks. The Danish, Swedish and German authorities have launched investigations that are still under way. But from an energy market perspective, there are already some important lessons.

The destruction of Nord Stream is likely to loom large in arbitration cases over Russian gas supplies to Europe last year. Uniper and RWE of Germany and Engie of France have filed claims that will be heard by an international arbitration panel in Stockholm, arguing that they are owed damages by Gazprom of Russia because of its failure to deliver contracted volumes of gas.

The standard model for the majority of Russia’s gas exports to the EU has been under long-term contracts. In Uniper’s case, some of those contracts stretched out to 2035. When critics complained about Europe’s dependence on imports from Russia, a European could respond that Gazprom and its predecessors had always honoured those supply contracts, through the Cold War and the political upheavals that followed.

In June of last year, that changed. The flow of gas through Nord Stream 1 fell sharply, with Gazprom blaming Siemens for its failure to return critical gas compressor units after maintenance. In July, flows were stepped down further, as Gazprom said more equipment needed repairs. Then at the end of August flows were shut off completely, and never restarted. Gazprom said oil leaks had forced it to shut down the one remaining operational compressor on the pipeline. Western governments argued that Russia was attempting to use gas as a weapon to undermine European support for Ukraine.

Uniper says Gazprom’s failure to supply contracted volumes, at a time when European spot prices were at record highs, caused it “significant financial damages”. Having to go out into the market to replace the lost Russian gas cost it at least €11.6 billion up to the end of November, Uniper said, and the figure is expected to keep growing through to the end of 2024. Klaus-Dieter Maubach, Uniper’s chief executive, said “ We are pursuing these legal proceedings with all due vigor: We owe this to our shareholders, our employees and the taxpayers."

Uniper had been Germany’s biggest purchaser of Russian gas, but other European buyers will also have suffered significant additional costs. Flows through Nord Stream 1 operating at full capacity were 55 billion cubic metres per year. As a rough first approximation, given an average European benchmark TTF gas price of about US$43 per million British Thermal Units, the total cost of buying gas in the market to replace Nord Stream 1’s volumes in the second half of last year would have been about US$40 billion.

The extra costs for Gazprom’s European customers will have been the difference between that amount and what they would have had to pay under their contracts for Russian gas. Uniper, RWE and Engie have filed their claims for damages on that basis, and other European buyers may follow suit.

After the flows through Nord Stream 1 were first reduced last summer, Gazprom declared force majeure, arguing that its failure to fulfill its contractual obligations was due to circumstances beyond its control. Now the pipeline has been rendered inoperable, the question of force majeure is likely to be a central issue in the arbitration proceedings.

Uniper rejected Gazprom’s claim of force majeure last July, and can be expected to dispute it again at arbitration. If proof emerges that the US was in fact responsible for the attack on Nord Stream, or even if the culprit just remains a mystery, then Gazprom’s case will carry much more weight. If it emerges incontrovertibly that it was Russia, given that the Russian government owns just over 50% of Gazprom, the assertions of force majeure will be much harder to sustain.

Given the fundamental breakdown in relations between Russia and the West, it might be thought that Gazprom could simply choose to ignore whatever verdict the arbitration panel hands down. That view would be a mistake. Gazprom is still seeking to sign sales agreements with other buyers around the world, and being seen as a supplier that abides by contract terms, including arbitration decisions in the event of disputes, is important for that. And the long-term future of relations between Russia and the EU is still uncertain. If, in some very different circumstances, Gazprom wants to resume its role as a supplier to Germany and other western European countries, in will have to resolve any outstanding issues from the tribunal.

Seymour Hersh argues that the US decided to wreck Nord Stream because “as long as Europe remained dependent on the pipelines for cheap natural gas, Washington was afraid that countries like Germany would be reluctant to supply Ukraine with the money and weapons it needed to defeat Russia.”

That argument is debatable. At the time of the explosions, no gas was flowing through the Nord Stream system, and it was already clear there was a good chance none would ever flow again. European governments have been working hard to reduce their need for Russian gas: Germany, for example has ordered five Floating Regasification and Storage Units to import LNG.

Olaf Scholz, Germany’s chancellor, commented in August: “Russia is no longer a reliable business partner… It has reduced gas deliveries everywhere in Europe, always referring to technical reasons that never existed. And that’s why it’s important not to walk into Putin’s trap.” Under the European Commission’s REPowerEU plan, the EU hopes to end its imports of Russian gas by 2027, “if all works well”, in the words of the commission’s executive vice-president Frans Timmermans.

The dependence scenario sketched out by Hersh is not impossible, at least until the latest wave of LNG supply starts coming on to world markets in 2026-27. Europe got through the winter of 2022-23 better than Russia had hoped, thanks in large part to the mild weather. But it still has at least three potentially difficult winters ahead if the war in Ukraine continues and tensions between Russia and the EU remain high.

In the longer term, though, Europe is likely to never again rely in Russia for its gas. Bombing the pipeline would have been a high-risk operation for the US, in terms of the consequences of being caught sabotaging infrastructure in allied countries’ waters that is part-owned by allied countries’ companies such as Engie and Gasunie. And it would have had only a short-term payoff.

For Gazprom, on the other hand, the damage to the pipeline could have a lasting benefit, potentially saving it tens of billions of dollars in compensation. Although that seems like it will depend on Russia not being identified as the perpetrator.

While the claims and counter-claims are still swirling, it is worth noting the words of Rosemary DiCarlo, the UN under-secretary-general, at the Security Council hearing this week. “While we don’t know exactly what happened beneath the waters of the Baltic Sea in September 2022, one thing is certain,” she said. “Whatever caused the incident, its fallout counts among the many risks the invasion of Ukraine has unleashed. One year since the start of the war, we must redouble our efforts to end it, in line with international law and the UN Charter.”

Footnote on the Nord Stream blasts: the environmental impact

One aspect of the Nord Stream explosions that has been wildly over-hyped in some quarters is their environmental impact. One television presenter on a popular cable news channel referred to the attack as “the single largest human-caused environmental disaster in all of history,” which does not even come close to being true.

The largest impact from the explosions was the release of methane remaining in the pipes. It could be seen bubbling to the surface of the Baltic, where it escaped into the atmosphere. An analysis by the UN Environment Program estimated that between 75,000 and 230,000 tons of methane were released that way. But as anyone with a modicum of scientific education knows, methane is non-toxic and occurs widely in nature. Even a release on this scale was not the worst environmental disaster that month, let alone in all of history.

To the extent that a methane release is a problem, apart from the waste of potentially usable gas, it is because of its impact on global warming. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, estimated to have 81-83 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide over 20 years, and 27-30 times the potential over 30 years. (It diminishes over time as the gas breaks down in the atmosphere to form carbon dioxide and water.)

It is important to keep the release in context, however. The energy industry worldwide released nearly 135 million tons of methane last year, according to the International Energy Agency. That means the Nord Stream leak accounted for just 0.06%-0.17% of the industry’s emissions. Put another way, the methane released by the Nord Stream explosions was at most equivalent to 15 hours of emissions from the global energy industry.

As the UNEP report put it, the “Nord Stream gas leak may be the highest methane emission event, but [is] still a drop in the ocean.”

In brief

The US has nominated Ajay Banga, the former chief executive of Mastercard, to be the next president of the World Bank. David Malpass, the current president, announced his resignation last week, after being criticised over his statements on climate change. At a conference last September, when Malpass was asked three times about his views on climate change and whether he agreed that “man-made burning of fossil fuels is rapidly and dangerously warming the planet,” he replied noncommittally and said: “I am not a scientist.” Two days later he said: "It’s clear that greenhouse gas emissions from human activity are causing climate change," but environmental campaigners argued that was too little, too late.

Banga’s current role is as vice-chairman of General Atlantic, a growth equity investment firm, where he has been an adviser to its climate-focused fund, BeyondNetZero, since it was launched in 2021. While he ran Mastercard it committed to a goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050, and then brought that goal forward to 2040.

The World Bank has been under pressure from governments and environmental groups to do more to address climate change, both by financing investments to curb greenhouse gas emissions, and by helping countries adjust to the impacts of a warming world. But as discussed in a recent article in the Financial Times, the Bank is facing a range of competing pressures from its stakeholders.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is planning to convene a forum to discuss the capacity market for the PJM Interconnection grid, to examine “how best to guarantee it achieves the objective of ensuring resource adequacy at just and reasonable rates”. Flaws in the capacity market reduced revenues from the most recent auction, held last June, by 24%, according to PJM’s independent market monitor. PJM in December proposed adjustments to its capacity market rules, which FERC approved this week. FERC noted that even though it had approved PJM’s proposals, “the continuing disputes and frequent complaints about how PJM operates its capacity markets from an array of stakeholders throughout the region merit a general review”.

A company called B2U Storage Solutions has brought online an energy storage facility in California using 1300 battery packs that previously powered Honda and Nissan electric vehicles. The site has a storage capacity of 25 megawatt hours. B2U says it is the largest such facility with reused EV batteries operational anywhere in the world. If the role of reused batteries for grid storage can be proven at scale, it could make a significant difference to debates about what to do when the growing numbers of EVs on the roads reach the end of their useful lives.

And finally: one of my main gripes about the hugely popular TV show The Walking Dead was that it completely failed to acknowledge the implications of the degradation of gasoline for a post-apocalyptic world. People just drove around everywhere, siphoning gasoline from tanks, as though it lasted forever. Now the Jalopnik blog has pointed out that another popular show with a post-apocalyptic setting, HBO’s The Last Of Us, has a similar problem.

Other views

Simon Flowers — How the Russia-Ukraine war is changing energy markets

Flor Lucia De la Cruz — Tracking the hydrogen market: from policy to project pipeline

Sean Harrison and Giles Farrer — Third wave US LNG: a $100 billion opportunity

Neivan Boroujerdi and Greg Roddick — Has Norway’s oil and gas tax stimulus been a success?

Max Reid — Sodium ion batteries: disrupt and conquer?

Jeffrey Sonnenfeld and Steven Tian — The world economy no longer needs Russia

Rebecca Leber — What Europe showed the world about renewable energy

Noah Smith — Don’t be a doomer

Naomi Oreskes — Eight billion people in the world is a crisis, not an achievement (I occasionally put a disclaimer in this section reminding readers that I am in no way endorsing the articles listed. I just think they are important or otherwise noteworthy. This is one of the times when that disclaimer is particularly important.)

Quote of the week

“Not so long ago, many argued that importing Russian gas was purely an economic issue. It is not. It is a political issue. It is about our security. Because Europe’s dependency on Russian gas made us vulnerable. So we should not make the same mistakes with China and other authoritarian regimes.” — Jens Stoltenberg, secretary-general of NATO, speaking at the Munich Security Conference, explained what he saw as the key lessons for the West from the war in Ukraine.

Chart of the week

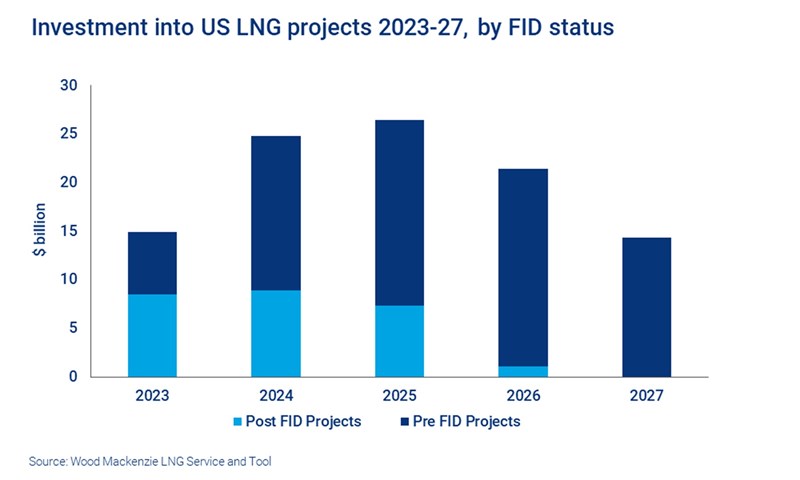

This offers another perspective on the outlook for US LNG exports. It comes from a news report from Wood Mackenzie’s Sean Harrison and Giles Farrer, looking at what they call the US$100 billion opportunity in the third wave of US LNG projects. The US is already set to become the world’s largest exporter of LNG this year, but its growth won’t stop there. High global gas prices, and the hunger for additional gas to replace lost supply from Russia, as described above, are creating the ideal conditions for continued growth in US exports. We are forecasting that by the end of the decade US LNG export capacity could grow by between 70 and 190 million tons per year. Export volumes could potentially more than double.

Realising that growth potential will require investment of up to US$100 billion, and this chart shows are expectations for how the money could be spent, building up to a peak in 2024-25. Note that most of the spending is expected to go to projects that have not yet reached a final investment decision. As Farrer says, 2022 was a bumper year for buyers signing contracts for US LNG, and that is driving projects forward. “Last year alone, 65 mmtpa of long-term US deals were signed, dwarfing the 18.5 mmtpa we saw in 2021,” he said. “This activity has pushed a host of pre-final investment decision (FID) US projects forward and we could see a wave of FIDs this year and next.” There is a lot more detail available in the full report.