Discuss your challenges with our solutions experts

Industry divergence on costs and turbine sizing manifests itself in the first commercial floating wind tender

A look at the outcome of the groundbreaking AO5 Sud de la Bretagne Tender, including the criteria that impacted the decision-making process and the implications for future tenders

5 minute read

Søren Lassen

Head of Wind

Søren Lassen

Head of Wind

Søren tracks, analyses and forecasts value chain dynamics, technological advancements and the market outlook.

Latest articles by Søren

-

Opinion

The Danish government charts course through offshore wind headwinds

-

Featured

Wind: predictions for 2025

-

Opinion

Industry divergence on costs and turbine sizing manifests itself in the first commercial floating wind tender

-

Opinion

Offshore wind energy: what to look for in 2024

-

Featured

Wind 2024 outlook

-

Opinion

Elevated subsidies enable offshore wind to end 2023 on a high note

The AO5 Sud de la Bretagne tender has now concluded. This was the world's first commercial floating offshore wind tender, marking a significant step in commercialising floating offshore wind technology, and highlighting the industry's diverse approaches to costs and turbine sizing.

The consortium of Germany’s BayWa and Belgium’s Elicio emerged victorious, with a bid of EUR 86.45/MWh to build the 270 MW Pennavel project.

We’ve taken a look at what led to this victory – and what it means for the offshore wind industry and tenders going forwards:

Price, robustness of the bid and turbine rating decided the winner

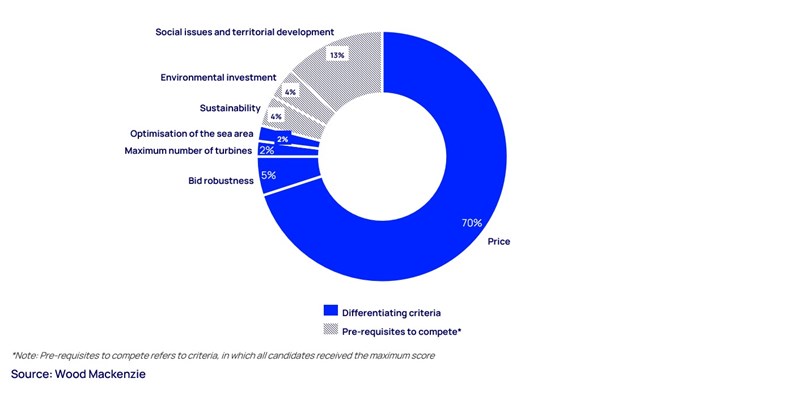

The tender process underscored the importance of several criteria. All six candidates met the essential requirements related to social and territorial development, sustainability, and environmental investment, which acted as prerequisites for competition.

The differentiating factors, however, were price (70%), the robustness of the contractual and financial arrangement (5%), the maximum number of turbines (2%) and optimisation of the sea area (2%).

This highlights the need for governments to not only consider the weighting of criteria but also to set high ceilings to ensure these parameters serve as genuine differentiators rather than mere entry requirements.

The price of the winning bid was 24% above the lowest bid price

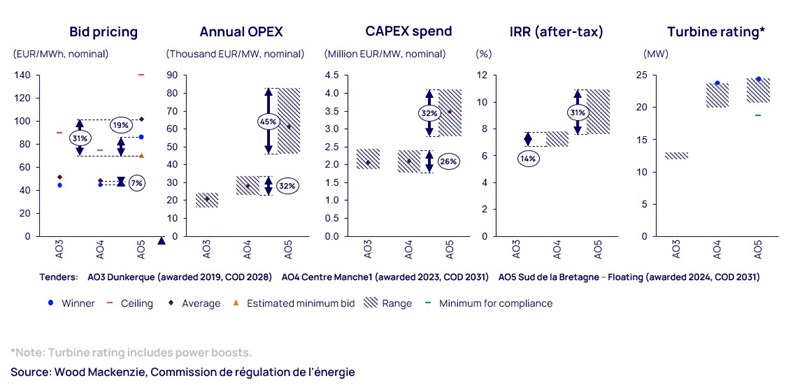

Price remained a critical factor, representing 70% of the scoring. Interestingly, CRE had initially selected a different winner, which offered a materially lower bid price than Pennavel. This can be inferred from the scoring of pricing:

The lowest bid scored the maximum of 70 points, with the remaining bids distributed in comparison to the lowest bid and the bid ceiling. Pennavel got the second-highest score by bidding 86.45/MWh, resulting in only 53.46 points. Based on the available information on bid scoring, it can be deduced that the lowest bid price was EUR 69.89/MWh, which was 19% below Pennavel’s bid, 38% below the average bid and only half the bid ceiling.

Pennavel received a total score of 81.96 out of 100. As all bidders got a maximum score for 21 of the criteria, it can be inferred that the company with the lowest price bid scored at least 91% and thereby won.

CRE initially awarded the company that secured the maximum price score. However, the company forfeited the bid, after which the runner-up, the Pennavel consortium, was able to claim victory. It is worth noting that three pre-qualified consortiums exited the tender before the results were awarded.

The French Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE) found the two lowest bids to be 'optimistic' and investigated the bids’ deliverability. However, CRE concluded that the winning bids allowed room for reconfiguration, which helps mitigate potential risks.

Subsequently, CRE recommended that future tenders should pay more attention to the robustness of the bids. Consequently, non-price criteria, especially relating to project deliverability, are likely to play a greater role in determining winners in future tenders.

The French government, whether intentionally or not, fuelled the arms race

Common to the winners of both AO5 and the previous round (AO4) is that their bids proposed the largest turbine ratings (23.8 MW and 24.5 MW, respectively – including power boosts). A caveat for AO5 is that the winner can reduce the turbine rating to 18.7 MW without forfeiting the contract. A contributing factor to the high turbine ratings is that these bids were submitted in 2021, at a time when the turbine OEMs had more ambitious plans.

Many factors led to the decision to go with larger turbines. Despite the low weighting of 4% for criteria relating to turbine rating (namely, optimisation of the sea area and maximum number of turbines), these factors did not have a ceiling, which allowed bidders to differentiate themselves by bidding with a larger turbine and score higher in the tender.

While the low weighting suggests that the important role of turbine rating was not intentional in this tender, it will add fuel to the heated ‘arms’ race debate that spans beyond France—especially since we are seeing the maximum number of turbines play a role in tenders outside of France too.

Divergent views on floating wind costs

The AO5 tender revealed significant disparities in cost assumptions among the candidates, reflecting the nascency of the floating wind sector and the tightening of supply/demand balances across the supply chain which is driving up prices and causing uncertainty over the costs of offshore wind – both bottom-fixed and floating.

The estimated figures for total investment varied by 45%, operating costs by 32%, and post-tax internal rate of return (IRR) by 31%.

These differences underscore the industry's divergent views on floating wind costs and highlight the challenges in establishing consistent pricing.

Notable technological and environmental commitments

Four out of six candidates opted for semi-submersible steel foundations, with the winning bid using semi-submersible concrete technology.

The offers estimated that turbine supply and installation would account for 32% of CAPEX, while floaters and anchors would make up 33%.

The tender design enabled several significant advancements in offshore wind sustainability. Candidates committed to limiting emissions during construction and operations and to high recycling levels across blades, towers and foundations. These commitments show the industry’s ability to improve the sustainability of offshore wind in other tenders as well.

Final thoughts

The AO5 tender exposes the offshore wind sector’s divergent views on core themes, namely pricing and turbine rating. Nevertheless, it marks a significant milestone in the commercialisation of floating technology and enables material strides away from its catch-22, which remains that governments want to see prices go down before tendering capacity, while developers want to see higher tender volumes in order to reduce prices. AO5 offers valuable insights into the sector and advancements of the project hold the potential to remedy the divergence of assumptions for future tenders.

Learn more

For the latest in offshore wind data and insights, click here to explore Wood Mackenzie’s comprehensive Offshore Wind Service.