Can Japan deliver its offshore wind potential?

Second offshore wind tender expected to close in June

4 minute read

Gavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin Thompson

Vice Chairman, Energy – Europe, Middle East & Africa

Gavin oversees our Europe, Middle East and Africa research.

Latest articles by Gavin

-

The Edge

A world first: shipping carbon exports for storage

-

The Edge

WoodMac’s Gas, LNG and the Future of Energy conference: five key themes

-

The Edge

Nigeria’s bold strategy to double oil production

-

The Edge

US tariffs – unpredictability is the strategic planners’ nightmare

-

The Edge

Upside pressure mounts on US gas prices

-

The Edge

The coming geothermal age

Almost totally dependent on imports to meet its coal, oil and gas demand and with a nuclear industry that has been through the wringer since the Fukushima Daiichi disaster in 2011, it is a miracle the Japanese economy still does what it does.

This makes any new source of domestic energy a big deal in Japan, though few have delivered. Optimism around methane hydrates came and went; proposals to develop geothermal resources spark outrage from owners of onsens, Japan’s famous hot springs; and despite launching the world’s first national hydrogen strategy in 2017, Japan's hydrogen market remains limited and development is highly uncertain.

This puts a greater emphasis on renewables. But once again, Japan can justifiably feel hard done by. Faced with numerous obstacles, the pace of onshore wind and solar project development across the country lags other industrial economies. Given this, the government aims to tender up to 45 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2040 to deliver the low-carbon electrons Japan needs.

To understand how Japan can fire up its offshore wind sector and drive future investment, I spoke to Yamato Kawamata, senior research analyst, in our Tokyo office.

What is the outlook for renewables in Japan?

Wind and solar have an essential role to play if Japan is to get close to its 2050 net zero target. But even with end-user tariffs among the highest globally, renewable developers are far from happy.

Typical project returns remain modest, while land constraints, high population density and rising local opposition to the permitting of wind and solar projects continue to delay both approvals and the pace of construction.

Without more supportive policies, we believe that renewables will struggle to hit the government’s target of 36-38% of generation by 2030. This is despite utility solar and onshore wind expected to be competitive with coal by 2030 and 2035, respectively.

Given ongoing issues with nuclear, any shortfall in renewables will need to be filled by thermal power generation.

Where are the bright spots?

Given the physical constraints facing onshore projects, offshore wind looks promising. Japan has 34,000 km of coastline and was among the first markets in Asia to examine the sector’s potential. Offshore wind resources are particularly attractive in Hokkaido and Kyushu.

Along with Europe and the US, Japan has been actively accelerating centralised tenders in the push for offshore wind growth.

But this is from a slow start, with investment only increasing after the Japanese parliament ratified offshore ownership regulations in 2018.

Progress is now being made, with Marubeni recently completing Japan’s first utility-scale offshore wind project. The success of the 140 MW Akita and Noshiro Port project, which also includes regional utilities such as Tohoku Electric, Kansai Electric and Chubu Electric, will be of critical importance as the government aims to rapidly increase offshore wind capacity.

Why is the Marubeni-led project so important?

The completion of the Akita Port project demonstrates that a utility-scale offshore wind project can be economically developed in a high-cost market like Japan. This will send positive signals to other developers, including non-Japanese companies such as bp, Orsted and SSE, who are partnering with local players to invest in the next wave of offshore wind projects.

But despite being Japan’s first operational utility-scale offshore wind project, the Akita Port project is unlikely to set a blueprint for others. Built in a port area, logistics were less challenging as opposed to mainstream offshore wind projects often far from the coastline. The project also utilised much smaller turbines less suitable to more challenging deeper waters.

Are modest returns hindering Japanese renewables?

We estimate that Japan will need around US$147 billion of investments in renewable energy and battery storage through 2030 alone. Attracting this level of investment will depend on supportive policies and acceptable returns for projects.

We see Japan’s offshore wind sector capable of delivering returns of up to 8-9%, excluding entry costs, though returns do vary by location. At the top end, this compares favourably to onshore wind at between 5-6%, while Japanese utility PV projects have typically struggled to get above a 3% IRR.

But these returns are risked. All developers are facing pressure from project and supply chain delays and cost inflation.

Wholesale price volatility is also a concern in Japan as renewable penetration increases. Price cannibalisation worsened in 2022, with 88 days when variable renewables’ share of peak exceeded 40% and solar crashed the wholesale market during the daytime.

Price decoupling between high price markets such as Tokyo and wind-rich areas such as Kyushu and Hokkaido could also impact offshore wind returns, depending on the expansion of cross-regional transmission lines to deliver output to major demand centres.

What next?

First up is Japan’s second offshore wind tender, which is expected to close in June. The tender offers revised terms to encourage wider participation in the offshore wind sector. We expect interest to be high from both domestic and non-Japanese companies.

We are also closely watching the development of floating offshore wind. Japan has a limited shallow sea area and developers face rising opposition to offshore wind developments in traditional fishing grounds. The government is pursuing an ambitious policy to maximise the use of floating offshore wind by freeing up Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). We await progress with interest.

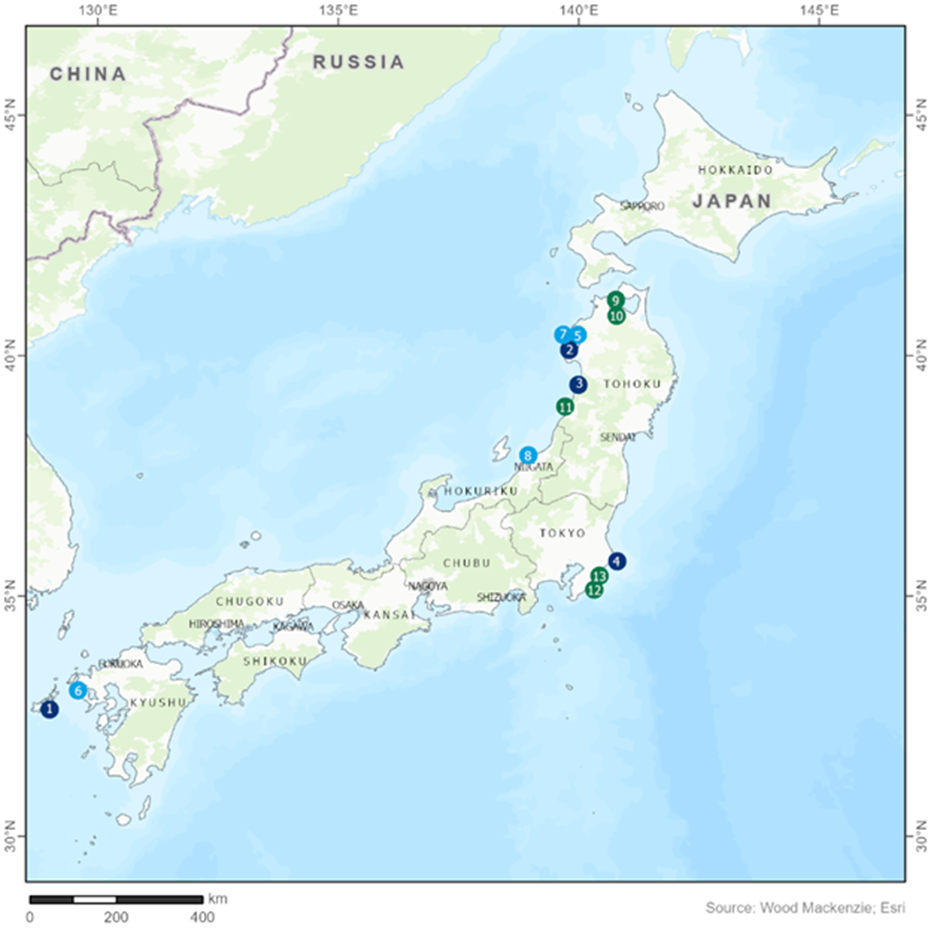

Areas opened for bids in second offshore wind tender (excluding 'preparation areas')