Geopolitics and the transition from oil to electric vehicles

Risks to the supply of battery raw materials

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Unlocking the potential of white hydrogen

-

The Edge

Is it time for a global climate bank?

-

The Edge

Are voters turning their backs on the EU’s 2030 climate objectives?

-

The Edge

Artificial intelligence and the future of energy

-

The Edge

A window opens for OPEC+ oil

-

The Edge

Why higher tariffs on Chinese EVs are a double-edged sword

Will geopolitics forever dog the transportation sector, even when electric vehicles (EVs) replace internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles? Simon Flowers investigates.

Today’s drivers – the consumers of 60% of global oil demand – have experienced many ups and downs in the 50 years that OPEC has influenced price.

Yet oil supply is more diverse than many commodities. OPEC has 30% of the market, but 20 countries, including non-OPEC producers, each contribute at least 1 million barrels per day (b/d), collectively accounting for 80% of global supply. The remaining 20 million b/d comes from a list of producers almost as long as the membership of the United Nations.

Raw materials used in batteries come from a far narrower supply base. Most EVs will use lithium-ion batteries, which have cathodes made of nickel, manganese and cobalt (NMC).

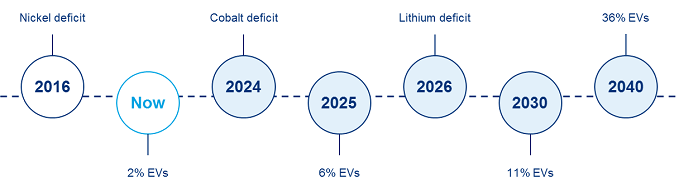

Demand for these metals will soar as the number of EVs climbs from nearly 5 million today to 300 million by 2040.

The transport sector’s current dependence on oil will gradually shift to these essential raw materials. I chatted to Milan Thakore, a research analyst here at Wood Mackenzie and author of Pulling the handbrake on the electric vehicle revolution? about the challenges of developing the supply needed to meet growing demand.

The cobalt conundrum

First is cobalt, which could prove a problem. Cobalt mineralisation is fairly widespread, but typically in low concentrations, and is mined as a by-product of copper and nickel. More than 20 countries produce cobalt, but the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is the main producer, accounting for 50% of the global resource and 64% of mined cobalt production in 2017. The DRC will account for 80% of global cobalt production by 2025.

Global cobalt demand is 114,000 tonnes, worth around $9 billion annually. (The DRC’s cobalt sales amount to one-sixth of its gross domestic product). Wood Mackenzie expects demand will triple to more than 300,000 tonnes by 2040. Even if the DRC ramps up production, we forecast that the market falls into deficit by 2024 and stays there.

Price would help incentivise investment in supply, but as cobalt is a by-product, the relationship is not straightforward. Quite how cobalt supply builds in tandem with demand is perhaps the great unresolved question of future EV hegemony. Throw in the DRC’s state of perpetual domestic armed conflict and it’s clear why cobalt thrifting shapes the strategy of battery makers. The industry is working to dilute the mix from today’s NMC 1:1:1 battery, to NMC 6:2:2 and eventually, beyond 2025, to NMC 8:1:1.

Nickel suppliers slow to respond to demand

Second, nickel is already in deficit, but there is little sign of producers gearing up to capitalise on the anticipated boom. The market is worth over US$30 billion annually, and global supply of 2.2 million tonnes per annum is dominated by two big producers - Indonesia (23%) and the Philippines (18%) – with a long tail of 30 other countries.

We expect demand to double by 2040, with EVs playing a significant role in this increase. Some new supply will come on stream over the next few years, but not enough to meet demand. Time is a concern as well - any new project will take at least five years to deliver additional volumes.

Lithium's looming deficit

Third is lithium, which we expect to be in deficit by 2026. It’s a $3.2 billion market, with current consumption pf 240,000 tonnes set to sky rocket to 1.7 million tonnes by 2040. Ore extraction in Australia and elsewhere has broadened the supply base, traditionally dominated by the “lithium triangle” salt deposits in Argentina and Chile.

China has a material influence on the market, controlling most of the chemical conversion facilities used to upgrade concentrates. As such, it is currently a bottleneck and potential single point of failure for the lithium market.

The electric vehicle, not a getaway from geopolticial risk

Weaning transportation off oil and onto EVs is one of the central planks of decarbonisation. Geopolitical risks around the supply of battery raw materials suggest that, in the absence of new, evolving battery chemistries, the EV era will be just as fraught as the present one.