Get Ed Crooks' Energy Pulse in your inbox every week

Trade becomes a new tactic for curbing emissions

The US and EU have agreed to draw up the world’s first carbon-based trade arrangement, covering steel and aluminium. It could create a powerful incentive for producers to cut emissions

1 minute read

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed Crooks

Vice Chair Americas and host of Energy Gang podcast

Ed examines the forces shaping the energy industry globally.

View Ed Crooks's full profileSteel is one of the great paradoxes of the energy transition. It is essential for low-carbon energy technologies: the weight of a wind turbine is typically about 70% steel, for example. But steel production is also a massive contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions. It accounts for about 7% of total carbon dioxide emissions from energy use.

A new trade agreement between the US and the EU attempts to start to resolve that paradox. The two economies have agreed to negotiate the “world’s first carbon-based sectoral arrangement”, covering trade in steel and aluminium, to reward metal produced with lower emissions. The Biden administration said the deal would “drive investment in green steel production in the United States, Europe, and around the world, ensuring a competitive US steel industry for decades to come.”

So far, all the two sides have is an agreement to agree. The new sectoral arrangement is scheduled to be completed by 2024, and in the meantime there is an interim deal that eases the burden of tariffs on EU steel and aluminium in the US, while lifting tariffs that the EU had imposed on a range of US products.

The hype is justified, even so. As the world moves towards a lower-carbon future, with different economies moving at different speeds, international trade in energy-intensive goods will become increasingly contentious. If countries with low costs and high emissions can sell freely into countries with high costs and low emissions, production will shift to those higher-emitting economies. To prevent that, several economies have been looking at proposals for carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs): import duties based on products’ associated emissions, intended to level the playing-field between imports and domestic producers that have been paying a price on carbon.

The EU is pressing ahead with plans for its CBAM. Joshua Firestone, a principal economist with Wood Mackenzie’s fiscal service, wrote in a new note this week that one economy’s implementation of a CBAM “may trigger a domino effect for carbon fees in many other countries, including the accelerated adoption of carbon charges or higher carbon prices”.

The US-EU steel and aluminium trade deal looks like the first of those dominoes to fall. The Biden administration says the US and the EU will “work to restrict access to their markets for dirty steel and limit access to countries that dump steel in our markets,” while inviting into the agreement “any interested country that wishes to join and meets criteria for restoring market orientation and reducing trade in high-carbon steel and aluminum products.”

Steel producers that want to drive down emissions have a number of options available to them. In a world on course to limit global warming to 1.5 °C, implying a fall of 93% in emissions from steel production by 2050, the industry would have to change radically, cutting conventional blast furnace production by about 85%, nearly doubling the use of scrap, and capturing about 60% of the residual emissions. Those changes would be “immensely tough to achieve, with significant hurdles to overcome”, a recent Wood Mackenzie note warned. But import duties linked to emissions are part of a policy framework that could shift the industry towards that pathway.

Wood Mackenzie’s Mingming Zhang suggests that the US-EU agreement could create a “two-speed steel industry”, with innovative producers exploring investment in low-carbon technologies and setting the stage for further expansion and productivity gains, while the others suffer shrinking market share and falling profitability.

However, administering this pioneering emissions-based tariff system will not be easy. Governments will have to watch carefully to be sure that steelmakers are not trying to circumvent the rules, says Cicero Machado, Wood Mackenzie’s principal analyst for steel in the Americas. And given that EU imports into the US are much greater than US imports into the EU, this is likely to be a more pressing issue for the US government. “Rules of origin are going to be very important,” Machado says. “The US is going to have to be sure that all the steel it imports on preferential terms is melted and poured in the EU.”

The administrative burden created by a CBAM is one reason why some have opposed them. John Kerry, President Joe Biden’s climate envoy, has also sounded sceptical, suggesting that they should be “a last resort”, implemented only if more co-operative efforts to drive down emissions had failed. But with the steel and aluminium agreement, the US and the EU are taking a first tentative step in that direction. There is a good chance that further steps will follow.

Headlines from the first week of COP26

COP26, the 26th annual Conference Of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, kicked off this week with music, short films and poetry, as well as speeches from Boris Johnson, prime minister of the UK, Prince Charles, David Attenborough, and Mia Mottley, prime minister of Barbados, among others. President Biden said the US was “not only back at the table but hopefully leading by the power of our example” and said his administration was “working overtime to show that our climate commitment is action, not words.” He also criticised presidents Xi Jinping of China and Vladimir Putin of Russia for their decisions not to attend the summit.

The most important substantive part of the COP26 process has been the number of countries setting net-zero goals for emissions by mid-century. After Saudi Arabia, India, Australia, Russia and Vietnam announced they would aim for carbon neutrality by dates between 2050 and 2070, countries responsible for almost 90% of global emissions have now announced a net-zero goal. These goals are very challenging indeed, and it seems likely that many will be missed. But even so, the direction of travel is clear.

The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero announced that 500 global financial services firms with $130 trillion under management – about 40% of the world’s total financial assets – had now agreed to align with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Mark Carney, the former governor of the Bank of England who is now vice-chair of Brookfield Asset Management and UN special envoy for climate action, said: “We now have the essential plumbing in place to move climate change from the fringes to the forefront of finance so that every financial decision takes climate change into account.”

More than 40 countries signed a pledge “to accelerate a transition away from unabated coal power generation,” by rapidly scaling up clean power and ceasing new construction of unabated coal-fired plants. The signatories include several big coal users, including Vietnam, Ukraine and Egypt, but exclude some of the largest producers and consumers including China, India, Australia and the US. Indonesia signed up, but with a qualification on the clause about not building new coal plants. The statement also commits countries to ending coal use “in the 2030s (or as soon as possible thereafter)” for major economies and “in the 2040s (or as soon as possible thereafter)” for the rest of the world, rather than the hard deadlines of 2030 and 2040 that had been proposed by the UN. Poland signed up for the commitment, but soon afterwards climate and environment minister Anna Moskwa said the country was not planning to phase out coal until 2049..

The US and EU have persuaded about 100 countries to sign up for the Global Methane Pledge, committing them to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030. The countries joining the pledge are responsible for nearly half the world’s methane emissions, and about 70% of its GDP, President Biden said. Russia, China and India were among the countries that did not sign up. To support the US commitment, the Biden administration has announced new regulations on methane emissions from the oil and gas industry.

Meanwhile, negotiations continue on finalising Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, the rules for international carbon markets and other cross-border programmes for emissions reduction.

The OPEC+ group sticks to its course

The Biden administration has for weeks been urging OPEC members and their allies in the OPEC+ group to increase production more rapidly, to help hold down the cost of fuel for American drivers. On Thursday the OPEC+ ministers had a chance to consider those requests, and emphatically rejected them.

At an online meeting, the ministers reaffirmed the plan agreed in July. That plan calls for them to increase output by 400,000 barrels per day every month, and they are sticking to that pace of expansion in supply, despite the rise in Brent crude to over $80 a barrel. The ministers made no allowance for the fact that some members of the group are struggling to increase production to their agreed maximum levels, which could potentially have been taken to allow more output from countries that do still have spare capacity, such as Saudi Arabia. And in a press briefing after the meeting, Prince Abdulaziz, the Saudi energy minister, delivered a robust response to critics who complained that oil prices had risen too far.

“Oil is not the problem, the problem is the energy complex that is going through havoc and hell,” he said, highlighting LNG prices in Asia and gas in Europe, which were about 400% higher than in March. “Look at what Brent is doing, the 28% that happened to oil is nothing.”

But although he and other OPEC+ ministers have rejected President Biden’s appeals, crude prices have been faltering over the past week. Some traders now expect the US to release oil from its Strategic Petroleum Reserve, as one of the few options open to it for directly influencing crude markets in the short term.

Ann-Louise Hittle, Wood Mackenzie’s head of Macro Oil, commented: “For OPEC+, doubts remain on the reality of the oil supply crunch. Wood Mackenzie is also cautious. Gas-to-oil fuel switching is not at the levels widely feared in the market of up to 2 million b/d. We estimate it is closer to 200,000-300,000 b/d and supply is adequate to meet demand… Furthermore, our forecasts remain subject to downward risk due to the impact of the pandemic on economic growth and mobility as some cities or countries continue to use lockdowns intermittently to control the pandemic.”

In the longer term, President Biden said in his speech to COP26: “High energy prices only reinforce the urgent need to diversify sources, double down on clean energy deployment, and adopt promising new clean-energy technologies so we don’t remain overly reliant on one source of power to power our economies and our communities.”

In brief

The difficulty of building new power lines in the US has been identified by analysts at Wood Mackenzie and elsewhere as a critical threat to hopes of putting the electricity system on a path to net-zero emissions. The problem was underlined by a vote in Maine this week, which went heavily in favour of a call to ban “high-impact” electric power lines in part of the state, and to make it harder for projects in the rest of it to secure approval. The vote is a blow to the $1 billion Clean Energy Corridor project, intended to bring electricity from hydro power plants in Quebec to customers in Massachusetts.

The project was opposed by the Sierra Club, which has argued that “we must do everything in our power to limit the extent of the climate change that is already making storms wetter and wildfires hotter.” In the case of the Maine project, it argued that hydro power should not be counted as zero-carbon electricity. Hydro Quebec says the greenhouse gas emissions from its plants are about 3% of those from gas-fired generation.

The fight for the corridor is not yet over: Avangrid, the company behind the Corridor project, has gone to court arguing that the vote to retroactively block a project that was previously legally permitted is unconstitutional.

A shortage of nitrogen fertiliser caused by soaring natural gas prices is threatening to reduce crop yields next year, the producer CF Industries has warned.

Total world greenhouse gas emissions from human activities appear to have remained “relatively constant” over the past decade, according to new research from the Global Carbon Project, an international group of climate scientists. The GCP’s latest annual Global Carbon Budget study suggests that while emissions from fossil fuels have been rising over the past decade, emissions from deforestation and other land-use changes have remained fairly stable, and carbon removals by forests and soils have increased. If the current rate of emissions continues, the scientists say, the world’s “carbon budget” for having a 50% chance of avoiding global warming of more than 2°C would be used up in 32 years.

And finally: another perspective on the methane challenge. Energy Pulse readers are probably most focused on emissions from the oil, gas and coal industries, but those sources account for only about 30% of methane created by human activity, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report. Agriculture and waste together account for 62% of methane emissions, with livestock alone responsible for as about much as the entire global oil, gas and coal industries combined. So any plan for reducing emissions as envisaged by the Global Methane Pledge must include a plan for agriculture, and particularly for ruminants such as cattle and sheep, which create about 90% of the emissions from livestock. Beef production alone is estimated to account for 5.9% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

A new report from the Breakthrough Institute, The Clean Cow, sets out a series of ways that current and future technologies could cut emissions from US beef production by almost 50% by 2030. The technologies include feed additives, land-use changes, and breeding lower-emissions cattle. The authors acknowledge that “achieving even a fraction of this reduction [in emissions] would require overcoming steep technological, scientific, and financial barriers that make widespread adoption infeasible today,” and say it needs support from government including R&D spending and tax breaks for low-carbon production. But there are signs that some US food and agriculture sectors are facing up to the challenge. The US dairy industry last year set a goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Embracing the technologies needed to drive down emissions from beef might at least help deflect the criticism that having meat dishes available at COP26 is “like serving cigarettes at a lung cancer conference.”

Other views

Simon Flowers — A COP26 wish list

Ram Chandrasekaran — EVs: the biggest lever in driving the energy transition

Ian Millhiser — A new Supreme Court case could gut the government’s power to fight climate change

Vijaya Ramachandran — Rich countries’ climate policies are colonialism in green

Jason Bordoff — The developing world needs energy, and lots of it

Robert Hefner — The world needs climate leaders who prioritize people over molecules

Quote of the week

“Gas prices of course are based upon a global oil market. That oil market is controlled by a cartel. That cartel is OPEC. OPEC controls more than 50% of the petroleum supply and more than 90% of the petroleum reserves. So that cartel has more say about what is going on. Now on top of it, you’ve got [an] oil and gas industry that can’t flip a switch after coming out of a pandemic, in the same way that you’re seeing with the supply chains.” — Jennifer Granholm, US energy secretary, defended the Biden administration’s response to rising fuel prices, saying its ability to influence the global oil market was limited. The rise in US retail gasoline prices to their highest level since 2014 is seen as a political problem for President Joe Biden. Secretary Granholm argued that rising oil prices “tell us why we’ve got to double down on diversifying our fuel supply to go for clean.”

Chart of the week

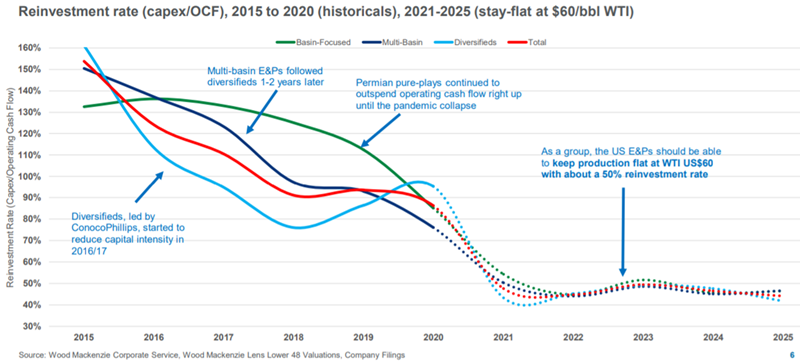

This comes from a recent Wood Mackenzie paper on US independent oil and gas producers. The rebound in oil prices means that cash flows at these companies have surged. Even if crude drops back some distance from current levels of around $82 a barrel for WTI, the independents should still be able to return cash to shareholders and reduce their debts. The y axis here shows the reinvestment rates —capital spending as a percentage of operating cash flows — needed to hold production flat, with WTI at $60 a barrel, for a sample of 23 US independents. The lines show different sub-sets of that group, with the red one representing the overall average. You can see that that average rate has already dropped significantly, from over 150% in 2015 to below 90% in 2020. This year and beyond, we expect it to drop to about 50%.

In other words, if WTI stays at around $60 a barrel, these US independents will be able to hold production steady while being able to use a little over half their operating cash flow for dividends, share buybacks, paying down debt, and investing in other areas such as emissions reduction technologies. They would also have the option of stepping up those reinvestment rates to increase production, or using the spare cash for acquisitions.